The D’Aranyi Sisters Play Spohr’s Duo in D minor 1927

Jelly d’Aranyi

Two sisters and outstanding violinists inspired several great musical works of the 20th century. Born in Budapest, Adila (1886) and Jelly d’Aranyi (1893) possessed royal musical blood. Their great-uncle was the esteemed violinist Joseph Joachim who it is said described Jelly with the following words, “a talent like her is born once a century.” The two young women rubbed shoulders with and inspired composers Béla Bartók, Maurice Ravel, Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst, and Edward Elgar.

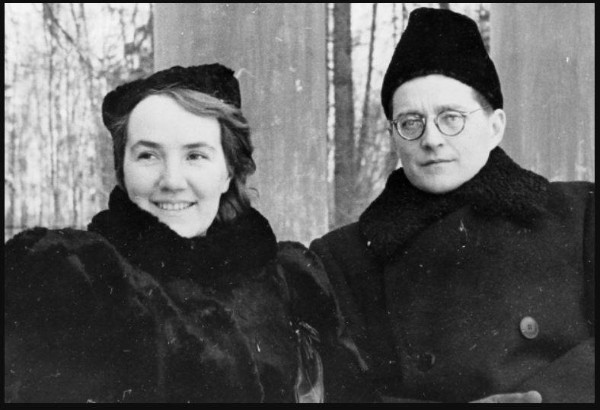

Adila d’Aranyi © SoundoftheLarkblog.com

Adila, the older of the two, studied at Budapest’s Liszt Academy of Music with Jenö Hubay and subsequently become perhaps the only private student of Joachim. She made her debut in Vienna performing the Beethoven Violin Concerto in 1906 on a Stradivarius violin bequeathed to her by Joachim. Jelly followed also studying with Hubay. Soon Jelly was performing joint recitals with her older sister, and by 1909 the sisters were drawing a great deal of attention receiving rave reviews from performances in Vienna and in England.

Jelly d’Aranyi Plays Poem Hongrois

They settled in London in 1913 on the eve of World War I. Jelly’s flamboyant and dynamic personality and burgeoning skills as a virtuoso inspired people to refer to her as one of the greatest female violinists of her time. Hubay wrote Six Poems Hongrois for her and one can hear exceptional virtuoso playing. The bowing techniques, with fancy string crossings towards the end of the Poem are effortlessly done in this 1928 recording. Listen also to her recording of Vitali’s Chaconne. Her sweet sound and somber interpretation is mesmerizing. One must point out that slides or portamento were very much the style in those days and Jelly’s tasteful use of glissando, quite exquisite in this recording, results in touching and expressive playing.

Jelly Plays Vitali’s Chaconne recorded in 1928 with piano

Adila married Alexander Fachiri and she performed all over Europe using her married name. Rebecca Clarke’s short piece for violin Midsummer Moon, an atmospheric and impressionistic work was composed for Adila and premiered in London’s Wigmore hall in 1924.

Rebecca Clarke: Midsummer Moon (Laura Kobayashi, violin; Susan Keith Gray, piano)

But soon everyone had a crush on Jelly, including Elgar and Bartók. The latter wrote two sonatas for Jelly, and the performances in 1922 and 1923 featured Bartók at the piano. Listen to the mysterious first movement of the Sonata No. 2 performed by James Ehnes. One can imagine Jelly taking full advantage of its free rhythms and folk-like melodies. Bartók wrote about the works in a 1924 letter: “The violin part of the two violin sonatas… is extraordinarily difficult, and it is only a violinist of the top class who has any chance of learning them…” He could’ve mentioned that the piano parts, too, are challenging!

Béla Bartók: Violin Sonata No. 2, BB 85 – I. Molto moderato (James Ehnes, violin; Andrew Armstrong, piano)

The Bach Concerto for Two Violins in D minor was a signature piece for the sisters. Hearing them play must have inspired Gustav Holst to write and dedicate his double concerto to the d’Aranyi women. The composer Ethel Smyth wrote her Concerto for Violin and Horn for Jelly, and the Australian composer and pianist Frederick Septimus Kelly, whom Jelly met as a teenager, wrote his Gallipoli Sonata for her before losing his life at the Battle of Somme in 1916. Jelly, in love with him, never married and for the rest of her life kept a photo of Kelly on her bedside table.

Gustav Holst: Concerto for 2 Violins, Op. 49, H. 175, “Double Concerto” – III. Variations on a Ground: Allegro (Sarah Ewins, violin; Janice Graham, violin; English Sinfonia; Howard Griffiths, cond.)

Ethel Smyth: Concerto for Violin, Horn and Orchestra – I. Allegro moderato (Thomas Albertus Irnberger, violin; Milena Viotti, horn; Vienna Konzertverein Orchestra; Doron Salomon, cond.)

In 1922 Jelly performed for a private salon that Ravel attended. Apparently, unable to get enough of her, he entreated Jelly to play several encores of Hungarian Gypsy Music. She accommodated and played well into the wee hours of the night. The consequence of this evening is of great historical importance as it became the inspiration for Ravel writing his much-loved showpiece Tzigane. Jelly performed the premier of the virtuoso work in 1924 in London. It begins with an extraordinary, rhythmically free and dramatic cadenza.

Maurice Ravel: Tzigane (version for violin and orchestra) (Henryk Szeryng, violin; South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden and Freiburg; Hans Rosbaud, cond.)

Portrait of Jelly d’Aranyi © National Portrait Gallery

During the early part of the 20th century spiritualism was all the rage. In fact, Adila, considered a psychic, wrote a book on the subject entitled Widening Horizons. Adila enticed Jelly to one of her séances and a very intriguing story ensued.

In the last years of his life composer Robert Schumann, incarcerated in an insane asylum, very shortly before his attempted suicide in 1853, completed a violin concerto for Joseph Joachim. Schumann is considered one of the greatest composers of all time, yet once Joachim had the concerto in his hands he, with the input of Clara, Schumann’s wife, agreed the work reflected poorly on Schumann. Didn’t it echo his madness? Joachim kept the manuscript and it remained unpublished. Subsequently it was held in the Prussian State Library with the stipulation that it be withheld until 100 years after Schumann’s death.

At Adila’s séance in 1933, Schumann’s ghost sent an urgent message to Jelly. Would she perform his long-lost concerto? Compelled by Schumann’s voice Jelly made arrangements for the premier with conductor Sir Adrian Boult and the BBC Symphony. But the young iconic violinist Yehudi Menuhin had somehow procured a copy of the manuscript and he wanted to premier the work in San Francisco in 1937. The Nazi regime, by then in power, intervened. The music to the Schumann Concerto and hence the copyright was held in Germany, and what better way to replace the now forbidden (Jewish) composer Mendelssohn and his Violin Concerto with a suitable German composition performed by a German soloist. (Menuhin was Jewish and Jelly was half-Jewish.)

Jelly d’Arányi (with Myra Hess at the piano), in a BBC studio in 1928

Ultimately the premiere took place in 1937 with the violinist Georg Kulenkampff and the Berlin Philharmonic. Hitler and Goebbels attended. Shortly thereafter Menuhin did perform the work giving the Schumann Concerto its American premiere in New York’s Carnegie Hall. Jelly had her opportunity. She performed the work with the BBC Symphony in 1938—its London premiere.

Ms. d’Aranyi was also an avid chamber musician. She formed ensembles with the renowned cellist Guilhermina Sillva in 1914, and with the cellist Felix Salmond and the pianist Dame Myra Hess in the 1930s.

Jelly’s health declined after World War II. She performed very little, only occasionally at private salons. She passed away in 1966.

Intrigued by this artist? Jelly’s story is told in Ghost Variations by Jessica Duchen—a fictionalized account of Jelly’s life but nonetheless historically accurate.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter