For the vast majority of his life, Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) was “a man easily satisfied, happy with his friends and colleagues, lacking the taint of ruthless ambition and egotistical self-promotion characteristic of so many, and without the pretension and hollow self-importance that marks lesser people.” He never looked for shameless self-promotion; instead, he let his music speak for him.

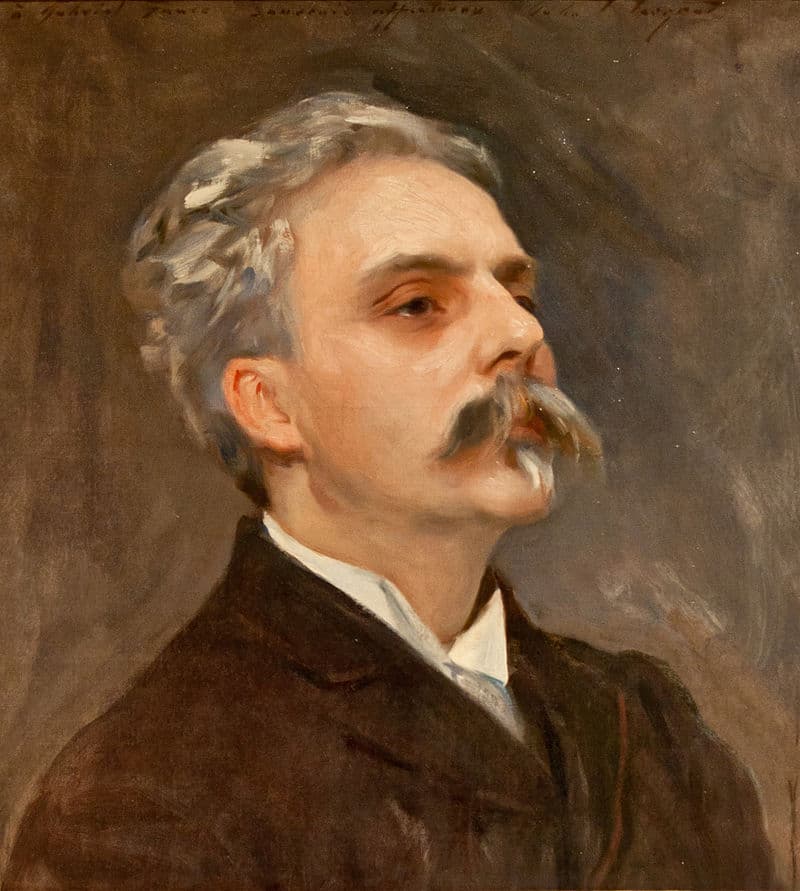

John Singer Sargent: Gabriel Fauré, 1896

Fauré developed a highly personalized musical style, reflected in soulful modal melodies and a colorful harmonic language. One of the most advanced French composers of his generation, official recognition came at a relatively late stage in his life. However, he was always considered a revered teacher and educator, and during his tenure at the Paris Conservatoire, he instructed Maurice Ravel, Georges Enescu and Nadia Boulanger, amongst countless others.

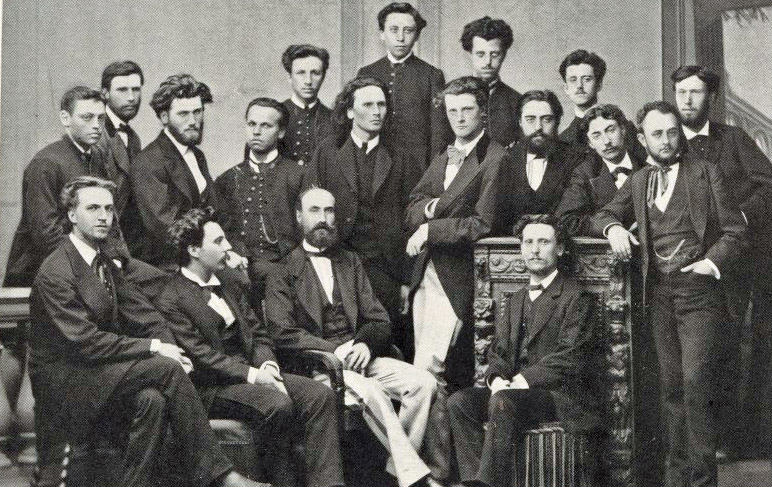

Gabriel Fauré (front row, second from left) in a group of staff and students of the École Niedermeyer, 1871

During his long career, he met important French composers, including Saint-Saëns, Lalo, d’Indy, Duparc and Chabrier, who became supportive friends. When Fauré battled with insecurities and short periods of depression, he was looking at his extended circle of friends for encouragement and support; let’s meet some of his most ardent supporters.

Gabriel Fauré: 3 Songs, Op. 7, No. 1”Aprés un Rêve” (Sandrine Piau, soprano; Susan Manoff, piano)

Camille Saint-Saëns, 1900 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b8424645h)

In 1854, young Gabriel was sent to Paris to prepare for the profession of choirmaster. Just one year earlier, Louis Niedermeyer had established the “Ecole de Musique Classique et Religieuse,” and Fauré would remain at the institution for a total of 11 years. In March 1861, Camille Saint-Saëns took charge of the piano department, and Fauré remembered, “After allowing the lessons to run over, he would go to the piano and reveal to us those works of the masters from which the rigorous classical nature of our programme of study kept us at a distance and who, moreover, in those far-off years, were scarcely known. … At the time I was 15 or 16, and from this time dates the almost filial attachment … the immense admiration, the unceasing gratitude I had for him, throughout my life.” Saint-Saëns, in turn, was delighted to have found an enthusiastic student, and at each step of Fauré’s career, “Saint-Saëns’s shadow can effectively be taken for granted.” Their friendship lasted for the better part of sixty years and was only temporarily clouded over the foundation of the Société Musicale Indépendante and over a difference of opinions regarding Hector Berlioz. Judging from their extensive correspondence, “Saint-Saëns was solicitous towards the younger man’s progress, helping him find his feet socially and professionally in Paris and helping to secure commissions. In all respects, the two managed the transition from teacher to friend with exemplary ease.”

Gabriel Fauré: Penelope (Norma Lerer, soprano; Jean Dupouy, tenor; Michele Command, soprano; Philippe Huttenlocher, bass; Jocelyne Taillon, mezzo-soprano; Jessye Norman, soprano; Alain Vanzo, tenor; Jose Van Dam, baritone; Christine Barbaux, soprano; Colette Alliot-Lugaz, soprano; Danielle Borst, soprano; François Le Roux, baritone; Paul Guigue, tenor; Jean Laforge Ensemble Choral; Monte-Carlo Philharmonic Orchestra; Charles Dutoit, cond.)

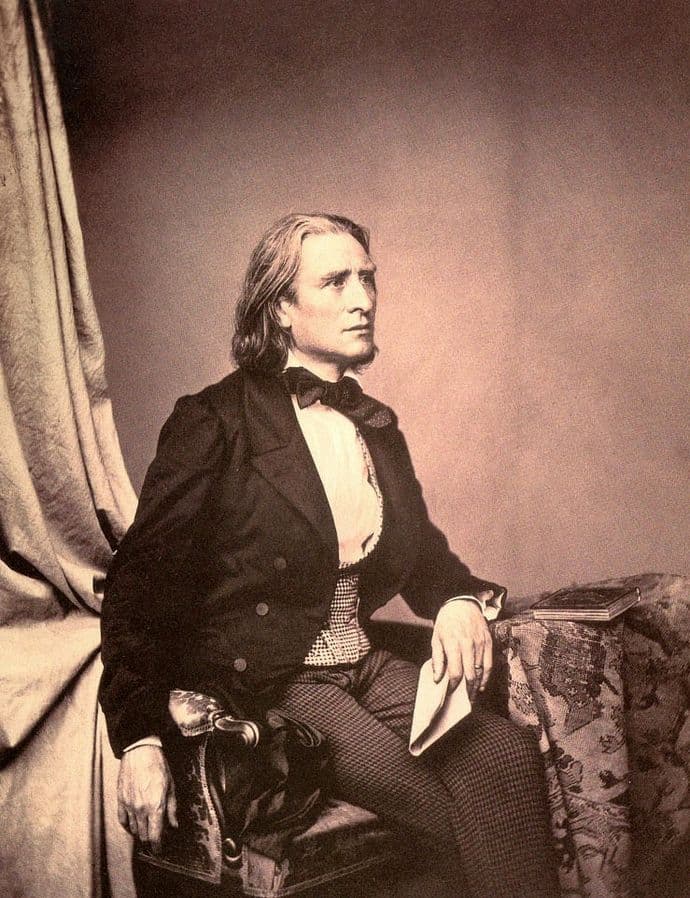

Franz Hanfstaengl: Franz Liszt, 1858

Saint-Saëns took Fauré on a pilgrimage to Weimar in 1877 in order to meet the great Franz Liszt. Liszt had long been one of Fauré’s musical heroes, and he later remembered. “First of all, I saw Liszt—what an emotional occasion! Saint-Sæns claims, I went green when he presented me to the master, and words cannot describe the welcome Liszt extended to me.” Liszt then played one of his own works and subsequently asked Fauré for one of his compositions. Fauré offered up his Ballade, Op.19, and Liszt began to play. Fauré reports, “After five or six pages, Liszt announced that he ran out of fingers and, to my terror, asked me to continue.” Essentially, Liszt cryptically declared the Fauré’s Ballade as too difficult. Liszt, of course, was capable of playing anything at sight, and he might simply have diplomatically indicated that he really didn’t like the piece. That opinion was subsequently shared by Claude Debussy, who dismissed the Ballade as “about as erotic as a woman’s loose shoulder strap.” However, Liszt clearly liked Fauré as he presented him with an autographed photo with the following inscription, “as a mark of my high esteem and sympathetic understanding.”

Gabriel Fauré: Ballade in F-sharp Major, Op. 19 (Yuja Wang, piano)

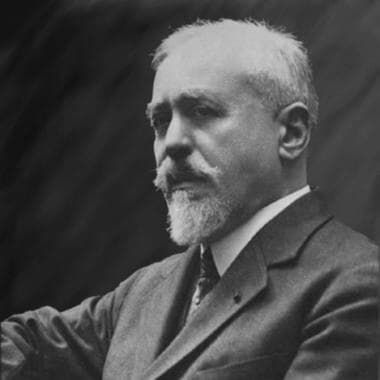

Paul Dukas

Gabriel Fauré and Paul Dukas (1865-1935) were both associated with the Paris Conservatoire. Their relationship evolved over the course of almost three decades, with Fauré taking on the directorship of that institution in October 1905. He made Dukas a member of the “Conseil Superieur,” together with Andre Messager, Alexandre Guilmant, and Rose Caron. Dukas regularly served on examination juries, and in 1909, Fauré offered Dukas the “prestigious post of professor of the ensemble class at the Conservatoire, a role left vacant by the death of Taffanel.” Dukas had primarily made his name as a critic, promoting a “historical and philosophical mode of musical enquiry that within the space of a few years already rendered his essays canonic in the eyes of peers.” Fauré was struck by the profundity of Dukas’ critical thought, which “he regarded as a marker of a serious, gifted mind.” Scholars have suggested, “Fauré’s status and seniority relative to Dukas in no way inhibited his ardent admiration for his younger colleague.” In fact, Fauré wholeheartedly promoted Dukas’ career prospects, and he even dedicated his 2nd Piano Quintet to him.

Gabriel Fauré: Piano Quintet No. 2 in C minor, Op. 115 (Cristina Ortiz, piano; Fine Arts Quartet)

Tchaikovsky, 1873

Travelling as an interpreter and secretary for a family friend during the summer of 1861, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky visited Berlin, Hamburg, Antwerp, Brussels, London and Paris. In fact, Paris would become one of his favorite cities, and he reports, “In Paris one cannot help becoming giddy and forgetting oneself. On the whole, life in Paris is extremely agreeable. In this place you can do anything you like, the only impossible thing being to feel bored. You only have to go out into the boulevards for your spirits immediately to rise.” Tchaikovsky habitually kept returning to the city of lights, and in 1886, he traveled from the Caucasus by sea to France. He would spend almost an entire month in Paris, “combining professional meetings with entertainment.” And that included meetings with Léo Delibes, Ambroise Thomas, and Gabriel Fauré. Fauré had just returned from his meeting with Liszt at Weimar, and Tchaikovsky declared “the First Piano Quartet as being excellent.” They met once more during Mach/April 1889, and a scholar observed, “Fauré deeply admired his Russian colleague, and presented him with signed copies of his First and Second Piano Quartets, the latter being inscribed To my dear master and friend P. Tchaikovsky from his affectionately devoted Gabriel Fauré.”

Gabriel Fauré: Piano Quartet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 15 (Faure Quartet)

Marcel Proust

The French novelist, critic, and essayist Marcel Proust (1871-1922) wrote that he was “intoxicated by Fauré music.” Proust organized a short concert to follow a festive dinner at the Ritz in Paris on 1 July 1907, and the evening commenced with Fauré’s First Violin Sonata. Proust reported to the composer Reynaldo Hahn, that it had been a “perfect and charming evening, and that the Princess de Polignac, Mesdames de Brantes, de Briey, d’Haussonville, de Ludre, de Noailles, and de Clermont-Tonnerre, enjoyed themselves thoroughly.” Sadly, Fauré had been scheduled to perform at the Ritz concert, but he had to withdraw because of illness. Proust was a devoted fan of Fauré’s music, once sending him a rather extravagant letter. “I know your work well enough to write a three-hundred-page book about it.” Proust goes on to describe his fondness for Fauré’s “way of wafting airy melodies over an unstable harmonic ground, and how familiar chords dissolve into one another in unfamiliar ways.” For Proust, Fauré’s music exuded bittersweet and complicated happiness that has been described as “open-air music rushing into a salon.” Fauré’s Violin Sonata might well have been the inspiration for Proust’s “Vinteuil Sonata,” a fictional music composition described in his novel “In Search of Lost Time.”

Gabriel Fauré: Violin Sonata No. 1, Op. 13 (Gil Shaham, violin; Akira Eguchi, piano)

Carl Timoleon von Neff: Pauline Viardot-García, 1842

Gabriel Fauré was considered extraordinarily attractive. According to contemporaries, “he had a dark complexion, a somewhat distant expression of the eyes, a soft voice and gentle manner of speech that retained the rolled provincial ‘r’, and a simple and charming bearing.” Women were drawn to him like moths to a flame, and stories of his romantic conquests became a mainstay of society gossip. His teacher and good friend Camille Saint-Saëns introduced him to the salon scene, and in 1872, he met the family of the famed mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot. Shortly thereafter, Fauré was passionately in love with Marianne, Pauline’s youngest daughter. He courted her for four years, and finally in 1877, they became engaged. That engagement lasted a mere three months, with Marianne suddenly breaking off the relationship. We still don’t know exactly what happened, but Fauré was deeply distressed, and he started to suffer from bouts of depression. By the way, Marianne was a fine singer and she did appear in a number of first performances of Fauré’s music.

Gabriel Fauré: “Rêve d’amour” (Marc Mauillon, baritone; Anne Le Bozec, piano)

Isaac Albéniz

Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909) was one of the most remarkable musical prodigies of all time. Apparently, his elder sister taught him to play the piano at the age of 1, and he first appeared in public with his own improvisations at the age of 4. By 7, he had applied at the Paris Conservatoire but was considered too young and thus studied at the Madrid Conservatoire. It is said that he ran away from home at the age of 9, boarding a ship to the Americas. Despite seemingly completely different personalities and musical styles, Albéniz and Fauré became good friends. In 1908, Albéniz introduced Fauré into the musical circles in Barcelona, and the following year, Fauré returned to conduct his “Ballade for Piano and Orchestra” with Marguerite Long as the soloist. Fauré was greatly distracted as he was awaiting the results of the election for his membership in the Institute. In the end, Fauré did get elected over some stiff resistance. It has been suggested that Albéniz had been passionately lobbying on behalf of his friend. Sadly, Albéniz was already seriously ill, and as he was staying in Paris, Fauré and Paul Dukas went to see him frequently. On one occasion, he paid Fauré the ultimate compliment when he asked Marguerite Long, as a last favor, to play one of his favorite piano pieces, the Second Valse-Caprice by Gabriel Fauré.

Gabriel Fauré: Valse-caprice No. 2 in D-flat Major, Op. 38 (Esteban Sanchez, piano)

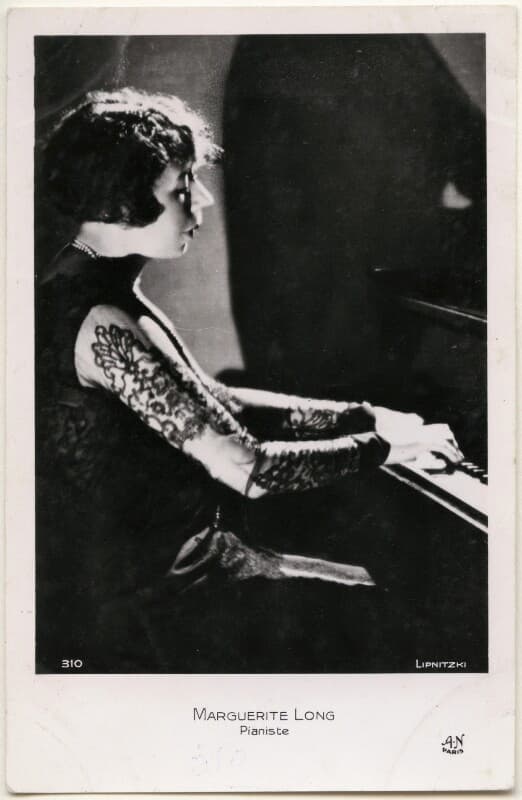

Marguerite Long

In 1903, Marguerite Long played Fauré’s third Valse-Caprice for the composer. Fauré was immediately impressed and asked Long to work on his newly composed Sixth Barcarolle. The following year, Long was planning an all-Fauré program, and the composer praised her for the “most ideal perfection.” And in 1906, Long was appointed Professor at the Paris Conservatoire by Fauré, who was the Director at the time. The pianist’s appreciation and advocacy of Fauré music and her deep immersion in the music gained her the reputation as the one who “best understood Fauré’s music, and whose sensitivity best captured its very distinctive flavour.” Her passionate promotion of Fauré’s music and her appreciation of the composer’s soft-spoken personal kindness and deeply set spiritual mastery cemented a close artistic friendship. Regrettably, the friendship between Long and Fauré turned bitter, and it was suspected that the composer’s relationship with pianist Marguerite Hasselmans might have been partly to blame. In addition, Long’s zealous promotion of Fauré’s music greatly irritated the composer. When Long proclaimed herself as “the sole heiress of the Fauré tradition,” he called her “a shameless woman who uses my name to get on.” None withstanding personal differences, Long continued to champion Fauré’s music as long as she lived.

Marguerite Long plays Fauré Ballade for Piano and Orchestra Op. 19

Paul Verlaine, 1893

Gabriel Fauré’s famous setting of “Clair de lune,” from Paul Verlaine’s collection “Fêtes galantes” is dedicated to his friend Emmanuel Jadin (1845-1922). Jadin was a painter by profession and an amateur pianist by temperament. In his dedication Fauré implies a gallant reference to Jadin’s relatives, a large and well-known family of court musicians at Versailles during the reign of Louis XVI. Louis-Emmanuel Jadin (1768-1853) was an outstanding member of the family, composing a substantial number of operas and giving piano lessons to Marie-Antoinette. The dedicatee of the song made his debut as a painter at the salon in 1868, having primarily studied with his father. Fauré composed his setting of the poem in 1887 for voice and piano, but at the instigation of the Princess de Polignac, he produced a delightful version for voice and orchestra.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Gabriel Fauré: “Clair de lune,” Op. 46, No. 2 (version for voice and orchestra) (Karine Deshayes, mezzo-soprano; Orchestre de l’Opéra de Rouen Haute-Normandie; Oswald Sallaberger, cond.)