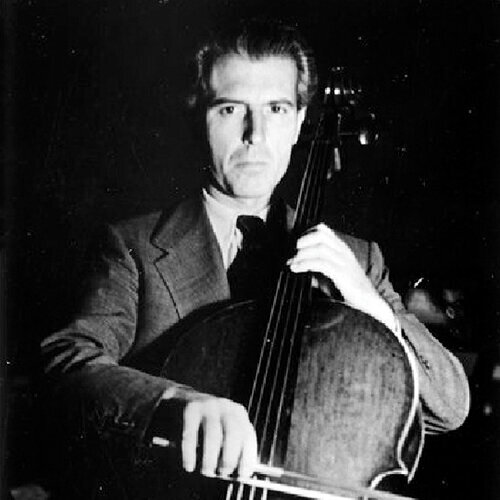

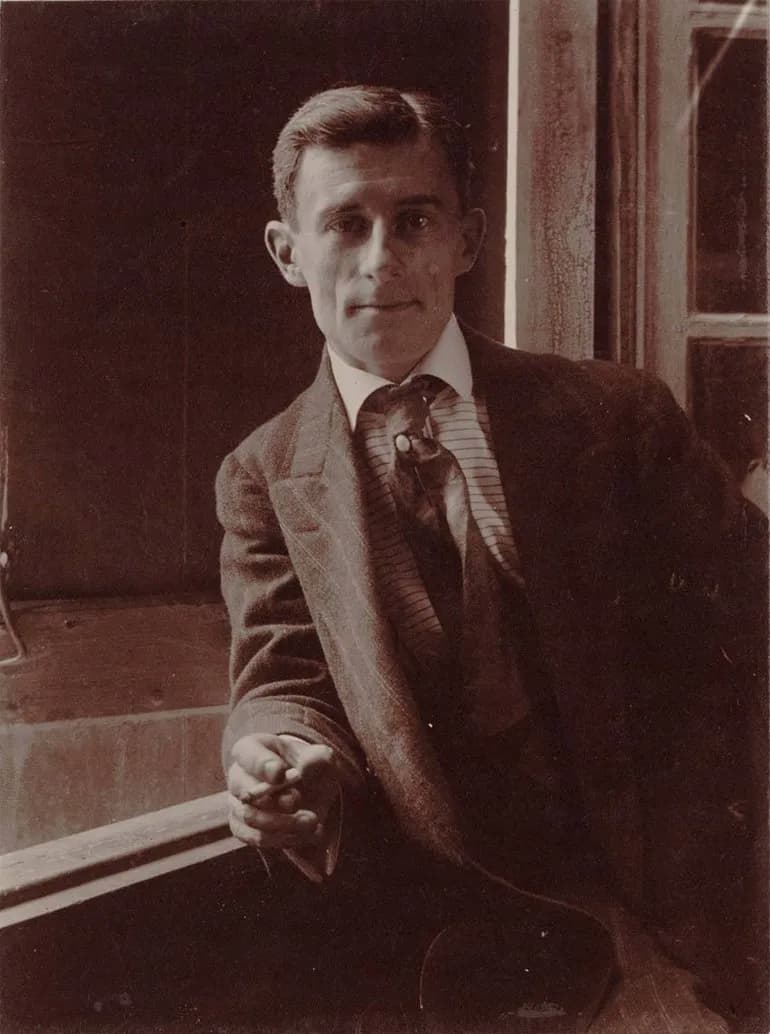

Felix Salmond

Felix Salmond (1888-1952) was one of the most influential cello teachers in America. As a professor at the Juilliard School, and later the Curtis Institute of Music, his pupils include Leonard Rose, Samuel Mayes, Orlando Cole, Bernard Greenhouse, Frank Miller, Eleanor Aller, Elsa Hilger, and others, who went on to teach another generation of outstanding cellists. And his playing was breathtaking and lyrical. Sadly, Salmond is most associated with the dismal premiere of the Elgar Cello Concerto.

He was born in England, to a distinguished musical family. His mother studied with Clara Schumann, and his father was a celebrated baritone. Felix first played both the violin and the piano, but he was drawn to the deeper resonant tones of the cello. His cello studies with William Whitehouse, a former student of Alfred Piatti, led to a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music, and by the age of 19, he went on to study at the Brussels Conservatoire.

His London debut in 1909 in Bechstein Hall, (now Wigmore Hall) impressed the critics and noted “his beauty of tone and smoothness of phrasing.” Salmond’s mother played the piano, with the composer Frank Bridge on viola, and Maurice Sons on violin, they performed the Brahms’ Piano Quartet in G minor, and premiered Bridge’s Phantasie Trio in C Minor. A recital debut followed—Beethoven’s Sonata in A major, Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations, Fauré Elegy, a Popper piece and Frank Bridge Serenade. Engagements started to pour in.

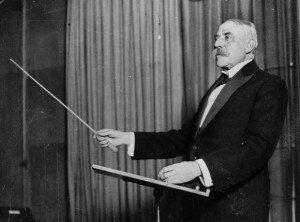

Despite the intervening war, he maintained concertizing, especially as a chamber music player. His participation in the 1919 premiere of Elgar’s String Quartet and the gorgeous Piano Quintet in A minor at Wigmore Hall, led to a long-term friendship with the composer. Elgar chose him for the first performance of his cello concerto. Salmond had assiduously worked on the solo part, but the conductor, Albert Coates—who was like many conductors, longwinded—ran out of time. Elgar barely contained his fury as he impatiently waited in the wings. Lady Elgar’s diaries shed some light on the situation, “Poor Felix Salmond in a state of suspense and nerves… Wretched and hurried rehearsal…that brute Coates…” Only because of Salmond’s preparation did Elgar agree to go ahead with the under-rehearsed London Symphony performance in 1919. It was a disaster. The critics lambasted the work.

Edward Elgar

According to the eminent music writer Tully Potter, it is not well-known that Salmond went ahead with a second performance in Manchester with the Hallé Orchestra in 1920. The critics were kinder this time, “Among works of its kind the Cello Concerto of Elgar will rank high. There appears to have been some want of judgment about its first performance in London, but there was no mistake on Saturday. Mr. Felix Salmond played most beautifully, with a polish and finish…lean and incisive technique… serene beauties of its melodies …”— The Manchester Guardian, March 1920. Salmond performed the concerto again in Birmingham, in 1920. Meanwhile, in London, Beatrice Harrison recorded the Elgar Concerto, and performed the work at Queen’s Hall with the composer conducting.

Despite well-received performances of Brahms Double Concerto and Don Quixote at Queen’s Hall with the LSO, Salmond believed his career would fare better in the United States. He emigrated and made his debut in New York in 1922, but he soon realized how few opportunities there were for cello soloists on orchestral programs—usually only one soloist per season. Salmond began to teach at Juilliard the first year it opened, in 1924, and the following year he was appointed head of the cello department at Curtis Institute, a position he held until 1942.

Edvard Grieg: Lyric Pieces, Book 3, Op. 43: No. 6. To the Spring (Felix Salmond, cello)

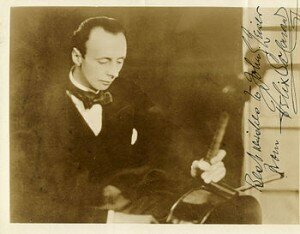

Musicians believe Salmond never recovered from the humiliation of the first performance of the Elgar. On the contrary, Potter writes. Salmond would have happily performed the American premiere of the Elgar Cello Concerto, but just as today, it is difficult to get an engagement, especially in New York. In November 1922, Belgian cellist Jean Gerardy, performed the Elgar Concerto in Carnegie Hall with the Philadelphia Orchestra, under the baton of Leopold Stokowski.

Salmond made his American orchestral debut just a few days later with the New York Symphony under Walter Damrosch, in works he became identified with—Kol Nidrei and Don Quixote. Potter cited a letter to Elgar from Salmond, dated December 1922, which indicates how much he hoped to perform the concerto the following season. But he was not hired to play in Carnegie Hall until 1924, and either the conductor or the managers requested Dvorak Concerto, a much beloved work then as now, with William Mengleberg and the New York Philharmonic.

Other engagements followed, in Boston, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia. Asked to play either the Brahms Double Concerto, Don Quixote, or Bloch’s Schelomo, Salmond did not have the opportunity to perform the Elgar Concerto until 1930. Since reviews about the composition were mixed, the magnificent piece would be relegated to the shadows for decades in the U.S. Salmond didn’t teach it unless asked.

Salmond’s playing, powerful, resonant and beautiful, was the result of his groundbreaking approach. Perhaps due to his physique—as he was very tall, with long arms—he carefully analyzed the fluidity of his bow arm, eventually advocating a bent thumb in the bow-hand, and using the weight of the arm for tone production. The cello, he said, “the singer par excellence of the [piano] trio… can sing soprano, contralto, tenor, and bass, and it is capable of equal beauty of tone in all of these registers.”

Beethoven: 7 Variations on Mozart’s Magic Flute aria “Bei Männern welche Liebe fühlen” recorded 1926

Felix Salmond

One of the first cellists to focus on the sonatas of Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, and Franck, Salmond felt these great works of the literature ought to be programmed on recitals, and not simply relegated to private settings.

As a teacher, he was demanding. If students didn’t work to their potential, he would react in the most acerbic and critical way. Orlando Cole once said about his lessons, “you had to go through hell…He [Salmond] would say, ‘What makes you think you can play cello? You’re wasting my time and your time. You have no talent!’”

Nonetheless, he was esteemed as an artist. A champion of contemporary composers—Georges Enescu, Frank Bridge, and Ernst Bloch—he gave the first performance in Britain, of Samuel Barber’s Sonata with Barber at the piano. Salmond continued to perform both in the U.S. and abroad, and had notable collaborations with artists of the day such as with Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Dame Myra Hess, and violinist Efrem Zimbalist. To learn more about this great cellist, read Tully Potter’s in-depth article.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Felix Salmond: Berceuse by Fauré and Largo from the Chopin Sonata (Op. 65)

Recorded for Columbia in 1928.