Just in case we need reminding, the “Dean of American Composers,” Aaron Copland was born on 14 November 1900. In his teens, Stravinsky studied theory and composition with Rubin Goldmark, who was considered one of New York’s most eminent composition teachers. Copland was always grateful to Goldmark, “for the kind of solid basic training that he gave me,” and he honoured him as “a musical pioneer and a genial and vivid teacher.”

Aaron Copland: Three Moods, “Embittered” (Leo Smit, piano)

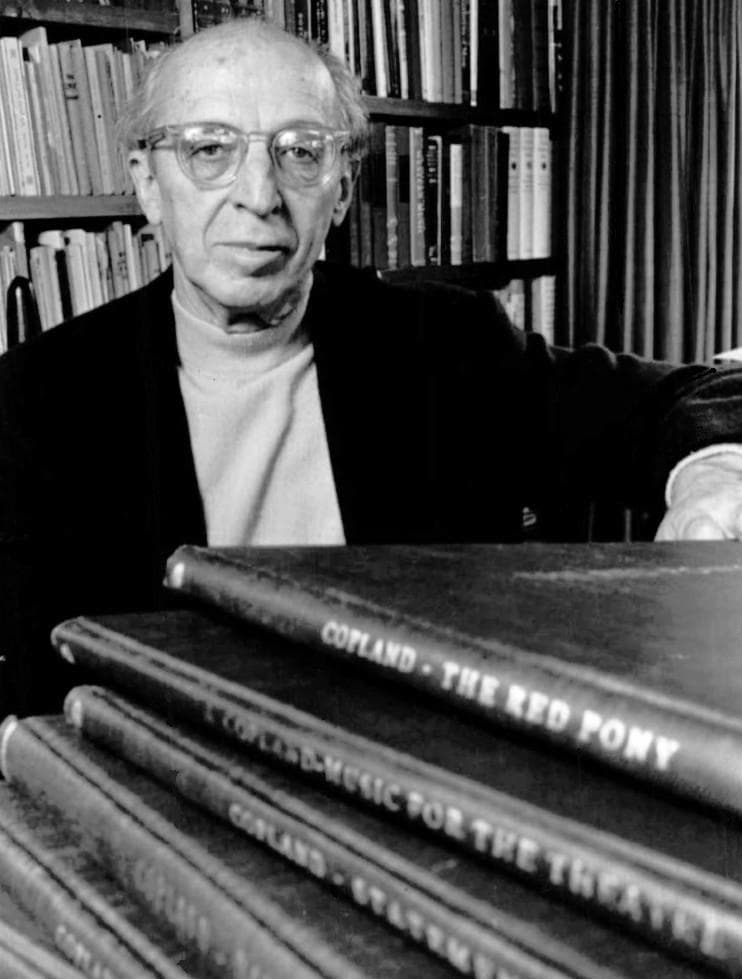

Aaron Copland in 1970

Goldmark apparently had little sympathy for the musical idioms of the day. He did admire Strauss, Ravel, and Debussy, but rejected Schoenberg and Stravinsky as “ugly,” and was convinced that German Romantic music represented universal ideals. Copland’s graduation piece from his studies with Goldmark was a three-movement piano sonata in a Romantic style. However, he had also composed more original and daring pieces, that he may or may not have shared with Goldmark.

Aaron Copland: Three Moods, “Wistful” (Leo Smit, piano)

The great majority of Copland’s juvenilia consists of short piano pieces and songs. As the composer writes, “During these formative years, I had been gradually uncovering for myself the literature of music. Some instinct seems to lead me logically from Chopin’s waltzes to Haydn’s sonatinas to Beethoven’s sonatas to Wagner’s operas. And from there it was but a step to Hugo Wolf’s songs, to Debussy’s preludes, and to Scriabin’s piano poems… As far as I can remember no one ever told me about modern music.”

Aaron Copland: Three Moods, “Jazzy” (Leo Smit, piano)

The Three Moods were only published in 1982, over half a century after they were composed. Copland originally titled them Trois Esquisses, and the first two pieces date from November 1920 and 1921, respectively. The “Jazzy” miniature was composed in Paris in July 1921, and it is the first time jazz appears in Copland’s music. When he premiered the Moods at Fontainebleau, he thought that “Jazzy” would “make the old professor sit up and take notice.” One month later, Copland took up his study with Nadia Boulanger.

Aaron Copland: “The Cat and the Mouse” (Leo Smit, piano)

Rubin Goldmark

Inspired by the La Fontaine poem “Le Chat et la Souris” Copland composed the Scherzo Humoristique: The Cat and the Mouse in March 1920. Copland claimed that he never showed the score to Goldmark, but still asserted that “he and his teacher came to a parting of the ways of the modernism of this little piece.” Some sources write that Goldmark reacted by “regretfully admitting that he had no criteria by which to judge such music,” and others report that Goldmark declared the work “very good-clever, musicianly and not too extreme for my tastes.”

I am not sure which version to believe, but one thing for sure. When Copland played the piece in Paris at the Salle Gaveau in 1921, the publisher Jacques Durand was in the audience. He saw Copland backstage and offered him a contract for the score, which would become Copland’s first published work. He tried to explain to his parents, “In the first place Durand & Son is the biggest music publishing firm in Paris, which means the world. To finally see my music printed means more to me than any debut in Carnegie Hall ever could.”

Aaron Copland: Four Piano Blues, “Freely poetic” (Leo Smit, piano)

Composed between 1926 and 1948, the set of short blues for piano can be performed individually or together as Copland finally grouped them. The order does not follow the order of composition, nor are the “blues” in any strict sense. The first two pieces were originally separate movements of an incomplete suite for piano, entitled “Five Sentimental Melodies.” The two concluding pieces were composed in 1947 and 1948, and are described as “the basis for some melodies of Copland’s Clarinet Concerto.

Aaron Copland: Four Piano Blues, “Soft and languid” (Leo Smit, piano)

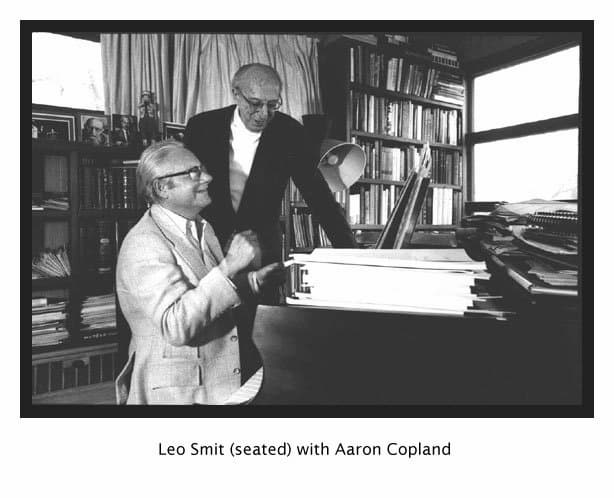

Once Copland had finished the Clarinet Concerto, he revised all four previously unpublished sketches and published them as Four Piano Blues. Each piece is dedicated to a pianist; the first to the renowned pianist and champion of Copland’s music Leo Smit. The second is dedicated to Andor Foldes, a pianist connected with the music of Béla Bartók‘s, and the third to William Kapell, a pianist killed in a plane accident. Finally, the concluding piece is dedicated to John Kirkpatrick.

Aaron Copland: Four Piano Blues, “Muted and drugged” (Leo Smit, piano)

Initially, Copland had reservations about “studying with a woman, but he quickly changed his mind. As he later wrote to Boulanger, “I shall count our meeting the most important of my musical life. Whatever I have accomplished is intimately associated in my mind with those early years, and with what you have since been as inspiration and example.” Most importantly, Boulanger told the young Copland that “you will do your best work if you explore what it means to be American,” and his interest in jazz idioms is delightfully disclosed in the Four Piano Blues.

Aaron Copland: Four Piano Blues, “With bounce” (Leo Smit, piano)

When composer Phillip Ramey rummaged among Copland’s files in 1977, he “discovered a neatly ink-copied, two-page piano piece that Copland had quite forgotten.” In the event, Ramey edited the 1947 work and they agreed on the title “Midsummer Nocturne.” A tender and lyrical bagatelle, it was originally intended to be part of a three-volume contemporary music series for young performers. The collection did not come to fruition, but Leo Smit premiered Midsummer Nocturne in Cleveland, on January 13, 1978.

Aaron Copland: Midsummer Nocturne (Leo Smit, piano)

William Kapell, 1948

Life Magazine commissioned Copland in 1962 to compose “a modern piece specifically written for young piano students by a major composer.” The resulting Down a Country Lane was featured in print across two pages. Copland explained, “the piece is descriptive only in an imaginative, not a literal sense. I didn’t think up the title until the piece was finished, it just happened to fit its flowing quality.” Copland also suggested that “even third-year students will have to practice before trying it in public.” In the event, the piece has a sweetly pastoral quality, and it is considered one of Copland’s most satisfying miniatures.”

Aaron Copland: Down a Country Lane (Leo Smit, piano)

Nadia Boulanger and her class in 1923 © Library of Congress

In 1953, Aaron Copland had to give testimony to a committee headed by Senator Joseph McCarthy on “un-American activities.” Basically, he was interrogated for his sympathies to the communist cause. Copland probably never did join the Communist party, but he was certainly sympathetic to their cause. As he declared, “I spend my days writing symphonies, concertos, ballads and I am not a political thinker.” The FBI didn’t buy his denial and continued to monitor his movements. To be sure, in the 1930s Copland freely mixed in communist and Marxist circles, and The Young Pioneers, musically describing a Communist Youth Movement, dates from August 1935. As Copland told the committee, “Musicians make music out of feelings aroused out of public events.”

Aaron Copland: The Young Pioneers (Leo Smit, piano)

One of the last pieces completed by Copland before Alzheimer put an end to his compositional activity was In Evening Air. It is prefaced by a quotation of words by Theodore Roethke: “I see, in evening air, how slowly dark comes down on what we do.”

This simple tonal piece is touching in the tenderness of its direct expression. As a scholar writes, “In an age of neurotic soul-searching and tension, Copland’s music of affirmation is a beacon of optimism worthy of the best in the American spirit.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter