What do you get when you add a piano to a string trio? That’s right, you get a piano quartet. Pairing a violin, viola, and cello with a piano is basically the standard instrument lineup for this type of chamber music, but piano quartets for other combinations have also been composed. In this blog, I will focus on the standard lineup because some of the most beautiful chamber music has been written for this classical ensemble.

The classical piano quartet instrument line-up: Piano, Violin, Viola and Cello

Like the piano trio, the piano quartet had to wait for the technical development of the piano, as it had to match the strings in power and expression. Let me introduce you to my personal list of the ten most beautiful piano quartets, starting with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, K. 493

The second piano quartet of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, K. 493 carries a lengthy inscription starting with “Quartetto per il clavicembalo o Forte Piano…” But once you actually hear the music it becomes immediately clear that the harpsichord was not really an option. Scholars suggest that Mozart probably had the Viennese fortepiano of the period in mind, as “the bright, distinctive tone and mechanical responsiveness provided the best means of achieving clarity of texture and an effective balance with the strings.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Mozart’s publisher had not been happy with Mozart’s first piano quartet, K. 478 as it “was too new and unfamiliar a genre, and the music’s depth of expression and complexity greatly exceeded the limits of popular taste.” The publisher added that the piano part contained too many technical difficulties “for the amateurs who were likely to be its purchaser.” Mozart was initially contracted to compose three piano trios, but the publisher pulled the plug after Mozart handed in his first. So why did Mozart go ahead and compose his second piano quartet nine months later? Nobody really knows for sure, but maybe he just wanted to convince his publisher that popular taste and good music are not mutually exclusive?

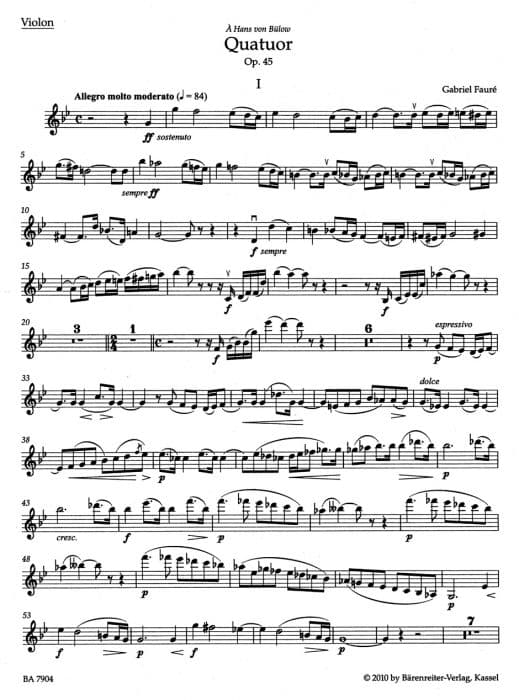

Gabriel Fauré: Piano Quartet No. 2 in G minor, Op. 45

Gabriel Fauré composed two piano quartets, and they are among the most loved pieces in the genre. It was a labor of love for the composer and not really an attempt at professional success. Fauré knew that “only successes in the theatre assured the reputation of a composer, and the Conservatoire had become a preparatory school for composers and performers destined to stock the theaters…composers were only considered if they could, when locked up by themselves, turn out a small operetta in no time flat for a special occasion.”

Fauré: Piano Quartet Op. 45

Fauré composed his second piano quartet between 1885 and 1886, presenting “a work of a higher level or architectural precision, formal and instrumental clarity; some insobriety is removed, as are some peaks of exaggerated intensity from his composition.” The “Adagio” is one of Fauré’s most beautiful compositions. The opening oscillating piano figuration is, in Fauré’s words, “an almost involuntary recollection of the distant bells of the town of Cadirac, which I heard as a child.” The single theme presented in the viola is delicately varied and transformed, and Fauré called it “A yearning of things that are not, perhaps: this is indeed the realm of music.”

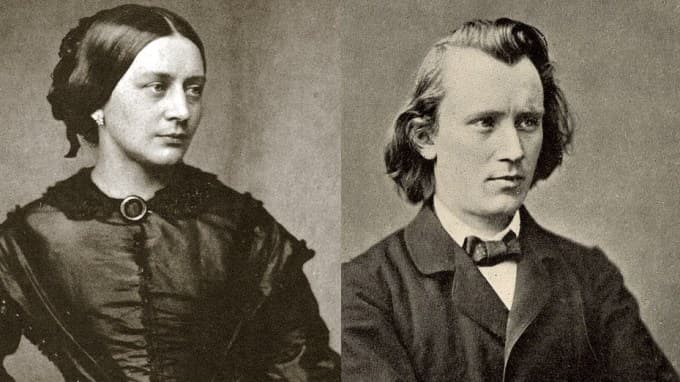

Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25

Johannes Brahms was twenty-eight when he composed his ambitious first piano quartet in G minor in 1861. He had started the composition in the 1850s, but as usual, took his time to refine and complete it. The premiere took place in Hamburg with Clara Schumann at the piano. Brahms actually claimed that while composing the quartet “he thought of Clara Schumann in every measure.”

Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms

A Brahms biographer writes, the music “is youth in all its distress, its raving bliss, its disappointments, its expectations of love and its courageous vitality, which nothing can misguide or confuse.” Brahms was always highly critical of his own compositions, but he really held his G-minor piano quartet in high esteem. He selected this particular work to make his debut as a pianist and composer in Vienna in November 1862. It was a spontaneous success with audiences, critics, and performers, and the violinist Josef Helmesberger exclaimed, “this is the heir of Beethoven.”

Brahms: Piano Quartet No. 1, Op. 25 – IV. Rondo alla Zingarese

One of the main reasons this quartet is so popular is found in the fiery and relentless “Rondo alla zingarese,” with its rousing and throbbing rhythms and striking accents in the “Hungarian style.” Interestingly, Arnold Schoenberg arranged the work for orchestra in 1937. When a critic asked Schoenberg why he had undertaken this task, he said: 1) I like the piece 2) It is seldom played, and 3) It is always very badly played, because the better the pianist, the louder he plays, and you hear nothing from the strings. I wanted once to hear everything, and this I achieved.”

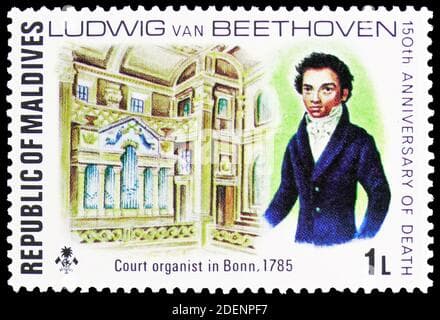

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, WoO 36, No. 1

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Quartet in E-Flat Major, WoO 36, No. 1 (New Zealand Piano Quartet)

Speaking of Beethoven, he was only fifteen years of age when he composed a set of three piano quartets. Completed in 1785, the piano quartet as a genre was still in its infancy at that time. A biographer writes, only the two works by Mozart “are significant contemporary contributions that are comparable.” Beethoven did not know the Mozart piano quartets, but he certainly knew the Mozart violin sonatas. Each of the three quartets of WoO 36 draws on specific works by Mozart, from the set published in 1781.

Stamp design featuring Beethoven in Bonn, 1785

The first of Beethoven’s quartets is modeled on Mozart’s K. 379/373a, the second on K. 380/374f, and the third on K. 296. These works are among the most substantial of Beethoven’s early compositions, and he would later reuse material in his early piano sonatas. The publisher Artaria printed the pieces only after Beethoven’s death in 1828, without opus number. These piano quartets might be seen “in the light of earlier traditions in which the keyboard took the lead.” Beethoven essentially abandoned the piano quartet in favor of the piano trio once he arrived in Vienna. The only exception is the arrangement for piano quartet of his Quintet for piano and wind instruments Op. 16.

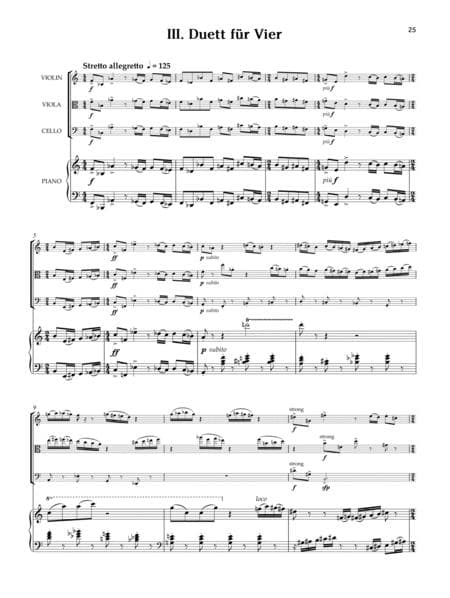

Danny Elfman: Piano Quartet

Danny Elfman: Piano Quartet (Berlin Philharmonic Piano Quartet)

Danny Elfman is known to millions of people for his more than 100 film scores, including blockbusters like Batman, Alice in Wonderland, and Man in Black. And if you watch television, you probably know that he also composed the famed theme music for both The Simpsons and Desperate Housewives.

Danny Elfman

A few years ago, Elfman came to the conclusion that he wanted to write music totally free from the influence of film. As he explains, “I came to the decision that I would take time off from my film work to write something for the concert hall every year, for as long as I’m alive and able. I found the idea incredibly liberating and relieving, like opening a pressure valve and letting out steam that had been building up for years. I was free from moving images, free to let musical ideas run amok. Most importantly, these works pushed me to new places far beyond my comfort zone.”

Danny Elfman: Piano Quartet 3rd movement

Initially, Elfman composed a violin concerto followed by a piano quartet. “I was once again faced with something to explore that I knew absolutely nothing about, and although the idea was intimidating, the presence of a piano gave me a bit more confidence, and I loved the freedom that the genre provides.”

Camille Saint-Saëns: Piano Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 41

Camille Saint-Saëns composed his piano quartet in B-flat major, Op. 41 in 1875. In fact, it was actually his second completed piano quartet, as he had composed a piano quartet in E major between 1851 and 1853. The E-major quartet was publically performed, but Saint-Saëns refused to have it published. As such, it was not made available to the public until 1992, when the manuscript was rediscovered and subsequently published.

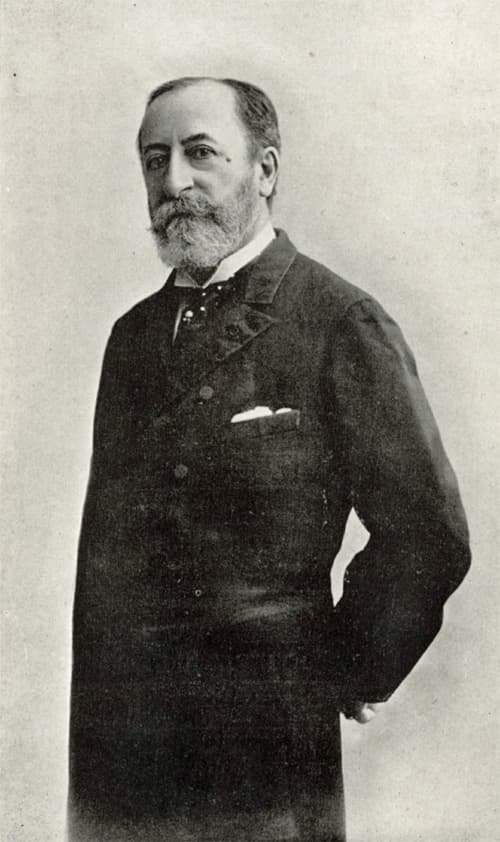

Saint-Saëns, circa 1880

In 1875, however, Saint-Saëns himself premiered the Op. 41 quartet on 6 March 1875 at Salle Pleyel with Pablo de Sarasate, Alfred Turban, and Léon Jacquard. Saint-Saëns had just gotten married, and his Danse macabre and his Fourth Piano Concerto were premiered and published to great acclaim. As a result, the piano quartet initially did not receive the attention it deserves, but it has since become a staple of the repertoire. Saint-Saëns was once again inspired by cyclic form, and “it would be hard to find a more vivid demonstration of the variety of French music making in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. However, it does not conform wholly to the casual cliché of French music as being light, graceful, charming, and anti-anything that might be classed as intellectual.”

Antonín Dvořák: , Op. 87

Antonín Dvořák wrote the first of his two piano quartets, Op. 23, at the age of 34. Initially, the publisher Fritz Simrock rejected the work, but later reminded the composer “I would gladly take a piano quartet, preferably even two.”

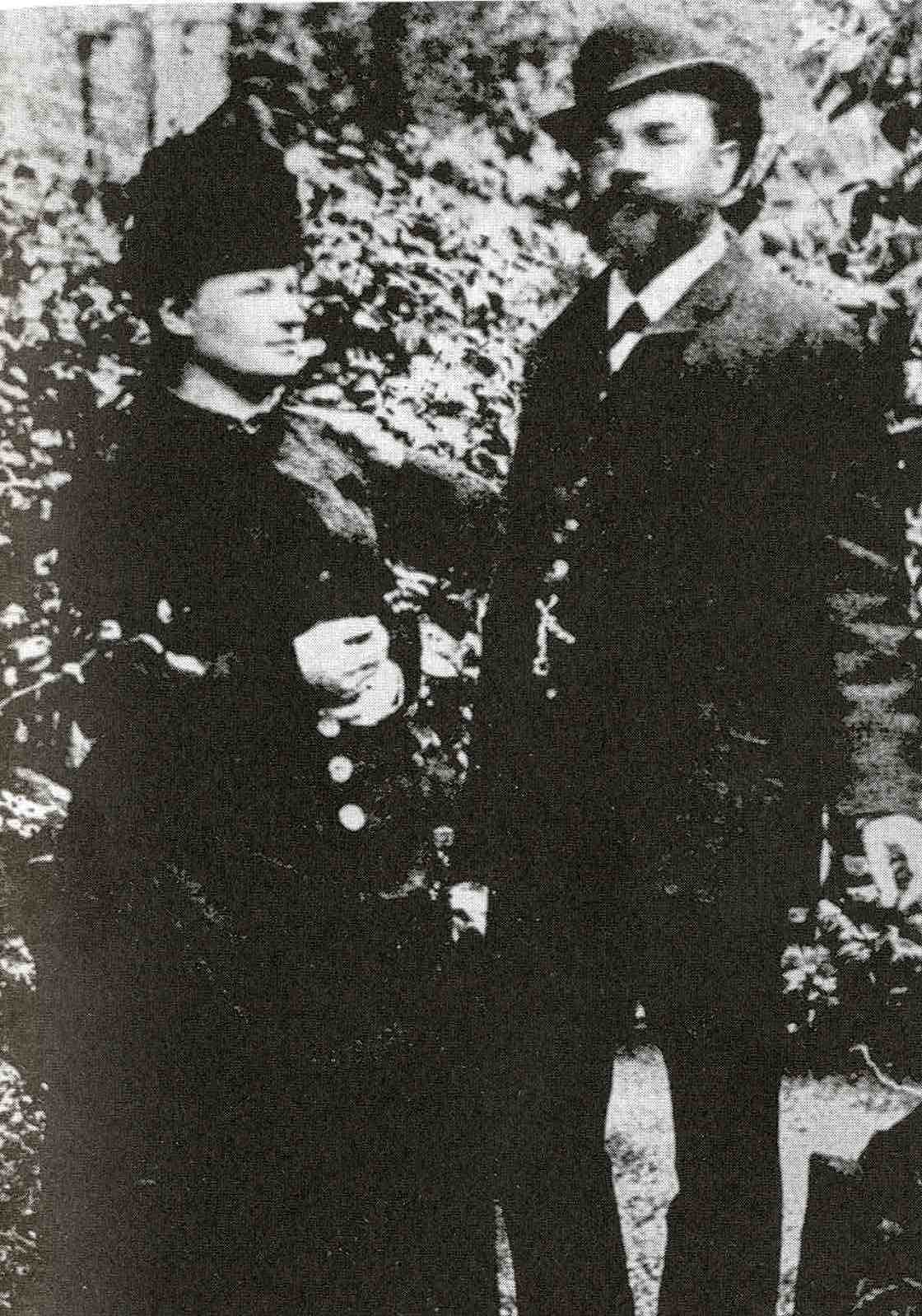

Antonín Dvořák with his wife Anna in London, 1886

But Dvořák had never forgotten the initial rejection. When he started on his second piano quartet in 1889, he informed the publisher that he had a “very slow hand,” but plenty of ideas. “My head is full of it… I have finished three movements of a new quartet with piano, and the finale will be ready in a few days. It has gone smoothly beyond expectation, with the melodies rolling into me.” And he wrote to a friend, “The quartet opens with a question-and-answer theme to take advantage of the contrast in sonorities between the piano and the strings. The strings, in unison, proclaim a muscular four-measure motive, and the piano gives a bantering, almost frivolous, reply. There is a contrasting second theme in the unexpected key of G major, but the two elements of the main theme dominate the development.”

Antonín Dvořák: Piano Quartet, Op. 87

In the event, Dvořák had created a work marked by melodic invention, structural mastery, harmonic richness, and irresistible high spirits. Even the normally grumpy critic Eduard Hanslick reported, “The quartet requires that the listener be considerably attentive and well informed, which, however, really pays off.”

Fanny Mendelssohn: Piano Quartet in A-flat major

Fanny Mendelssohn: Piano Quartet in A-Flat Major (Renate Eggebrecht, violin; David Cann, viola; Friedemann Kupsa, cello; Stefan Mickisch, piano)

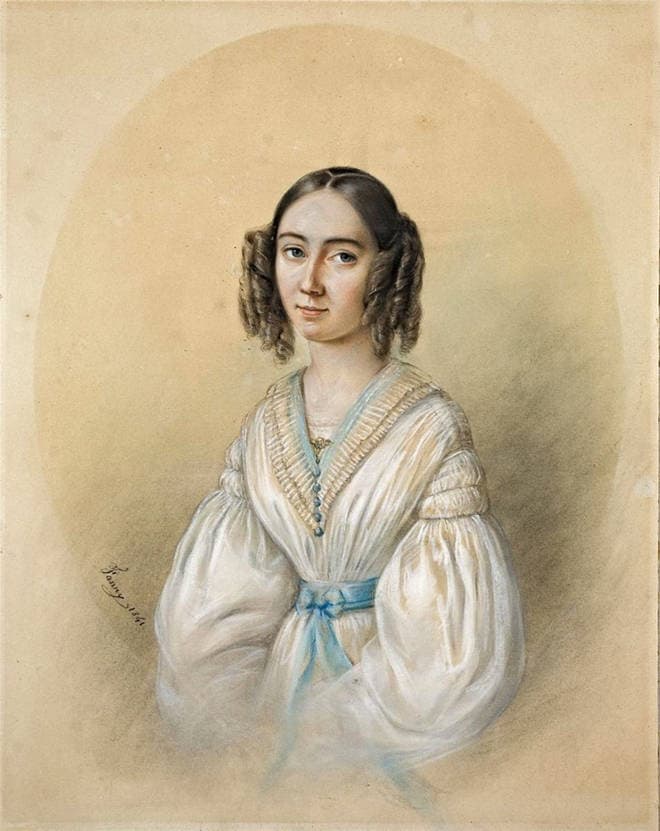

The brother and sister duo of Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn composed four piano quartets between them. Three are attributed to Felix and the piano quartet in A-flat major to Fanny. In 1822, both Fanny and Felix composed a piano quartet each with brilliant piano parts for performance at the weekly matinées at the Mendelssohn household. Fanny was four years older than her brother, and she displayed prodigious musical talent. At an early age, she was an outstanding pianist, and she was soon composing songs and piano pieces.

Fanny Mendelssohn

Initially, Fanny took great delight in mentoring her younger brother, and from 1819, both took lessons in counterpoint and composition with the great pedagogue Carl Zelter. Zelter initially thought that Fanny had the greater talent, and he considered her a natural-born composer. Her piano quartet was composed under Zelter’s guidance, and it unfolds in three movements. Critics have suggested that the work “shows her inexperience in a certain squareness of phrasing and in occasional harmonic transitions that are more surprising than convincing.” At the same time, her thirteen-year-old brother composed his piano quartet in C minor. His quartet was published as his Op. 1, while her work was only brought to light in the late twentieth century.

Bohuslav Martinů: Piano Quartet, H. 287

Bohuslav Martinů composed his piano quartet in 1942, after having left Paris for America. Actually, the piano quartet was one of the first works he completed in his new home. “While his technique was deeply affected by Ravel and he was surrounded by atonal experiments, his music still retained some of the unmistakable marks of his Czech predecessors and contemporaries.”

Bohuslav Martinů in New York

In the opening movement, in which the piano shares equally with the strings, some commentators have found traces of Moravian folksong. The entire quartet is full of contemporary harmonic techniques, but the most striking feature in this piece, “is the rhythmic structure at all levels.” It mimics many European folk traditions for “triple rhythms to alternate with duple to create interesting syncopations.” When I first listened to this piano quartet, I was rather confused. But then I listened to the last movement several times in a row before I listened to the entire work from the beginning again. And only then did the work make sense to me, and it has since become one of my favorite piano quartets.

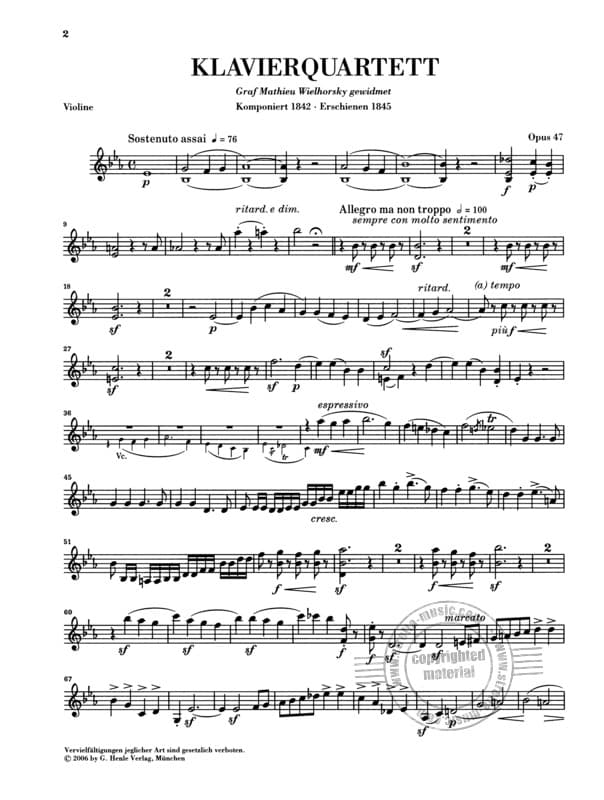

Robert Schumann: Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 47

I want to complete this blog with my all-time favorite piano quartet, Robert Schumann’s E-flat Major piano quartet, Op. 47. Composed immediately after he had finished his piano quintet, the piano quartet never really achieved the same popularity. It has been suggested that the reason is found in Schumann’s elimination of the second violin, “as it reduced the tonal brilliance of the ensemble and added to the dominance of the piano.”

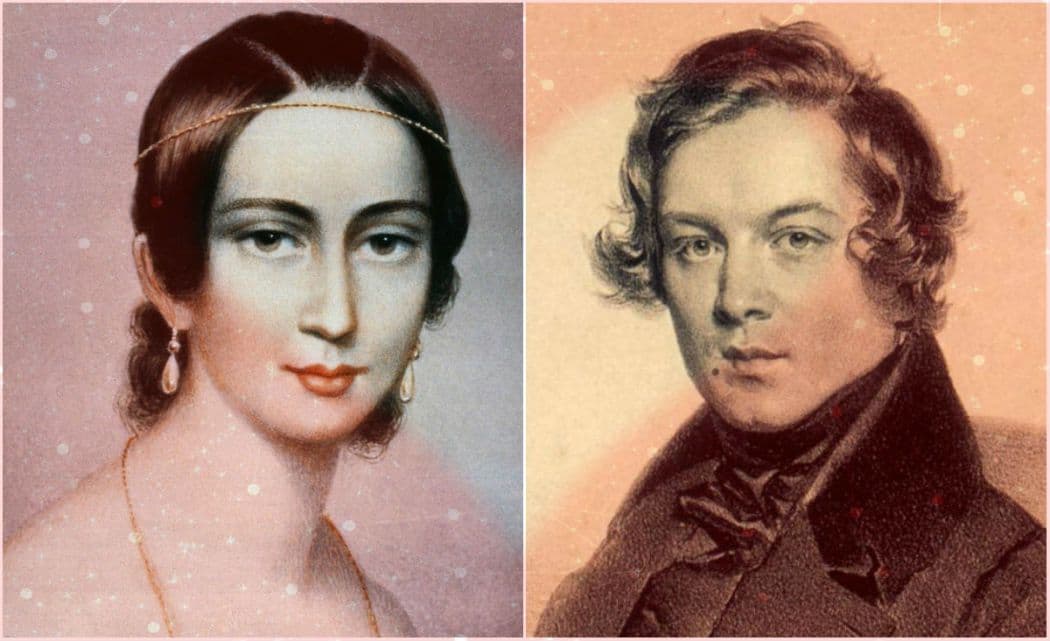

Robert and Clara Schumann

The reason Schumann got interested in chamber music in the first place was because Clara Schumann was on a brilliantly triumphant concert tour in Copenhagen. Robert went through a period of depression, possibly an early phase of his mental illness. He was unable to compose and instead got really interested in beer and champagne. In addition, his father-in-law was spreading the rumor that Clara and Robert had broken up. Schumann got over his depression by launching into an intensive study of the chamber works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, and he continued his study when Clara returned home in April.

Robert Schumann: Piano Quartet, Op. 47

To my ears, some of the anguish he experienced during this difficult period of his life is an integral part of the quartet. Clara played the piano for the premiere and called it “a beautiful, youthful, and fresh work.” How many beautiful piano quartets did I have to leave out in this blog? I am sorry that I could not include them all, but please let us know in the comments what other piano quartets you would like to see featured.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Cool article. Turina’s piano quartet is really fun too

Some nice works. But Danny Elfman is seriously out of his depth in this grouping.

I have recently made acquatance with the quartet of Josef Suk, a minor op. 1, and I must confess that I was overwhelmed. This piece could without further notice take a place among the best!

Herbert Howells wrote a superb quartet in A Minor. It should be played much more often than it is.