Jean-Delphin Alard’s motivation for uttering the immortal words “marry your violin, my son, never a woman” to his most famous charge, the teenage violinist Pablo de Sarasate, might have been twofold. For one, he was rather unhappily married to the daughter of Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, the most illustrious member of a prominent French family of violinmakers. The reason for his unhappiness, however, had little to do with Miss Vuillaume herself; he simply preferred the company of men. However, to project a veneer of respectability at his place of work — he held the position of professor of violin at the Parisian Conversatoire from 1843 to 1875 — he felt compelled to marry a woman! As such, his joy and fulfillment in life was intimately bound to his fine collection of violins, including among others, the Antonio & Girolamo Amati of 1603, the famed Messiah Stradivarius of 1716, and the Alard Guarneri del Gesú of 1742. Secondly, he clearly recognized the exceptional talent of his Spanish student Pablo de Sarasate, who had made his way to Paris at the tender age of 12, and simply sought to protect him from repeating his own mistakes. However, Alard did not dish out his professional and paternal advice without provocation! But let us start from the beginning.

Jean-Delphin Alard’s motivation for uttering the immortal words “marry your violin, my son, never a woman” to his most famous charge, the teenage violinist Pablo de Sarasate, might have been twofold. For one, he was rather unhappily married to the daughter of Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, the most illustrious member of a prominent French family of violinmakers. The reason for his unhappiness, however, had little to do with Miss Vuillaume herself; he simply preferred the company of men. However, to project a veneer of respectability at his place of work — he held the position of professor of violin at the Parisian Conversatoire from 1843 to 1875 — he felt compelled to marry a woman! As such, his joy and fulfillment in life was intimately bound to his fine collection of violins, including among others, the Antonio & Girolamo Amati of 1603, the famed Messiah Stradivarius of 1716, and the Alard Guarneri del Gesú of 1742. Secondly, he clearly recognized the exceptional talent of his Spanish student Pablo de Sarasate, who had made his way to Paris at the tender age of 12, and simply sought to protect him from repeating his own mistakes. However, Alard did not dish out his professional and paternal advice without provocation! But let us start from the beginning.

Pablo de Sarasate: Les Adieux, Op. 9 (Tianwa Yang, violin; Markus Hadulla, piano)

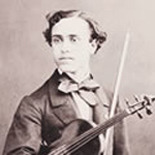

Sarasate originally hailed from Pamplona, located in the Spanish province of Navarre. His father, a musician, soldier and conductor of the 30th Pamplona Regiment Band, began to teach violin to his highly talented four-year old son. At the age of 10, Sarasate appeared publicly for the first time, accompanied by the La Coruña Theatre Orchestra. His performance was well received, and the widowed Countess Doña Juana Maria de Vega financially supported his continued musical education with Manuel Rodríguez Sáez in Madrid. Sarasate quickly became a celebrity, and even performed at the Royal Palace, home of Queen Isabella II. The Queen was mightily impressed and donated an annual endowment to fund his musical tuition. In addition, he received funding from the Regional Government of Navarre, and in July 1856, accompanied by his mother, he started his journey towards Paris. For a while, everything hung in the balance, as his mother suddenly died of a heart attack on route. Sarasate himself fell violently ill with a cholera infection, but in the end, managed to arrive safely in Paris. He was quickly adopted by the Lassabathie family, and started his studies with Alard. One year on, he won First Prize for Violin at the Conservatory, and in 1858 another first prize for his studies in Harmony. In the meantime, he came into contact and formed friendships with Rossini, Saint-Saëns, Lalo, Liszt, Rubinstein, Gounod and Meyerbeer. Yet, the relationship that really mattered to him at this time — surely the result of raging adolescent hormones — was Marie Lefébure-Wély. She was the daughter of the distinguished French organist and composer Louis Lefébure-Wely. Daddy Louis, not unlike Sarasate, had been a child prodigy, who began his studies of music at the age of 4. Admitted to the Paris Conservatoire in 1832, he studied organ and piano and in due course became titular organist at the church of Saint-Sulpice in 1863 — arguably the most coveted organist position in all of Europe. In addition, by joining forces with the famed organ builder Cavaillé-Coll, he also played a substantial role in the development of French symphonic organ music. I suppose, he was somehow surprised when the 17-year old Sarasate made an announced house call, and formally asked for his daughter’s hand in marriage. The meeting, of course, did not go well at all. We don’t know if the young lover was ridiculed or taken seriously. The result, however, was inevitable, as Marie quickly agreed with the wishes of her father that there was going to be no wedding, no way, never and Amen! Sarasate was shattered, and looked upon his teacher for advice, which Alard duly delivered. Interestingly, Sarasate did follow his teacher’s recommendation and quickly composed his “Les Adieux” Op. 9 for piano and violin. The composition is dedicated to Mlle. Lefébure-Wély, and was simply his way of saying goodbye, not only to Marie but also to the concept of marriage. Sarasate never mentioned Marie again, and he never got married, at least not to a woman or a man! Instead he did marry his violin and embarked on a long and extremely satisfying career as a composer and virtuoso violinist. After all, teacher knows best!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter