At the bottom of the brass section sits the tuba, the largest of the brasswind instruments. Oddly enough, for an instrument that is so fundamentally important, it, like the saxophone, was one of the last additions to the orchestra. It replaced the ophicleide (see saxophone for information).

Modern bass tuba (Yamaha)

The first bass tuba patent was granted in Germany in 1835 to Wilhelm Friedrich Wieprecht and Johann Gottfried Moritz. This was a valved instrument. After the bass tuba, Moritz’s son Carl Wilhelm invented the tenor tuba in 1838, now better known as the euphonium.

The Tenor Tuba, or Euphonium (Yamaha)

Before the invention of valves, a bass instrument such as the tuba was impossible. Valve-less instruments were confined to the overtone harmonic system, which doesn’t get into scale-like motion until you’re in the third octave above the fundamental. This is why the first brass instruments were high-voiced, like the trumpet. The development of valves in the 19th century made things much easier for the development of the lower voices.

The tuba’s role in the orchestra is not simply to provide support for the upper brass section, but to reinforce the lower wind and string instruments. Most orchestras have one tuba and most brass bands have two. Marching bands may have many more, usually in the round-the-body shape of the Sousaphone, made by the American instrument maker J.W. Pepper and named for American bandmaster John Philip Sousa.

Sousaphone, 2011

In Gustav Holst’s tour around the solar system, his first planet, Mars, uses the euphonium for the war calls of the God of War.

Gustav Holst: The Planets, Op. 32 – I. Mars, the Bringer of War (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Adrian Boult, cond.)

Modest Mussorgsky’s depiction of cattle in Pictures at an Exhibition relied on the tuba for its plodding depiction of the large animal.

Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition Pictures at an Exhibition (arr. M. Ravel for orchestra) – IV. Bydlo (Ukraine National Symphony Orchestra; Theodore Kuchar, cond.)

In addition to appearing in orchestral music from Berlioz to Bruckner and Wagner to Gershwin, the tuba has an extensive repertoire of concertos written for it, largely in the 20th century.

One of the best-known tuba concertos is Ralph Vaughan Williams’ work from 1954. Its premiere was given by the London Symphony Orchestra under John Barbirolli with Philip Catelinet as soloist. At first regarded as an eccentric work by an aging composer (he died in 1958, age 85), it is now regarded as a monument not only to the instrument but to music itself, with its inspiration from Bach and Beethoven. The final movement builds to the cadenza which demands the most from the player.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Bass Tuba Concerto in F Minor – III. Finale: Rondo all tedesca: Allegro (John Fletcher, tuba; London Symphony Orchestra; André Previn, cond.)

Written for the centenary of the Boston Pops Orchestra in 1985, John Williams’ Tuba Concerto was written for the orchestra’s tuba player, Chester Schmitz. The treat comes in the third movement where ‘virtuosity and velocity meet’.

John Williams: Tuba Concerto – III. Allegro molto (Dennis Nulty, tuba; Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

Japanese composer Dai Fujikura wrote his tuba concerto for tubist Øystein Baadsvik. Fujikura found the tuba to be ‘one of the sexiest instruments’ and thought it sad that its capacity for melodic playing was often set aside for its role as bass supporter. Fujikura says ‘. In this concerto, the solo tuba has a long, wide range of melody which I hope sounds quite sensual’.

Dai Fujikura: Tuba Concerto (Øystein Baadsvik, tuba; Geigeki Wind Orchestra Academy; Tokyo Kosei Wind Orchestra; Shizuo Z Kuwahara, cond.)

Kalevi Aho’s Tuba Concerto (2000–2001), was written for Harri Lidsle, tubist for the Lahti Symphony Orchestra. Aho had been interested in the tuba for some years, particularly in his opera Insect Life, where the main character plays the tuba and there’s a demanding cadenza in one of the scenes for tuba and alto sax. Aho focuses on the song-like, cantabile, quality of the tuba and has created a work that focuses on that aspect, placing virtuosity and technique to the background. At the end, Aho asks for multiphonics when the tubist music both sing and play at the same time at the end of the finale.

Kalevi Aho: Tuba Concerto – III. Larghetto – Presto – Tempo I (Baadsvik, Øystein; Norrköping Symphony Orchestra; Mats Rondin, cond.)

Armenian composer Alexander Arutiunian wrote his tuba concerto in 1992 and it was given its premiere by Harri Lidsle with the Lahti Symphony Orchestra. Like Aho, he wanted the tuba to sing and has created tunes with a folk-like atmosphere for the instrument. In the finale, in rondo form, starts with a melodic figure in the form of a circle and ends with a ‘dreamy cadenza’.

Alexander Arutiunian: Tuba Concerto – III. Allegro ma non troppo (Øystein Baadsvik, tuba; Singapore Symphony Orchestra; Anne Manson, cond.)

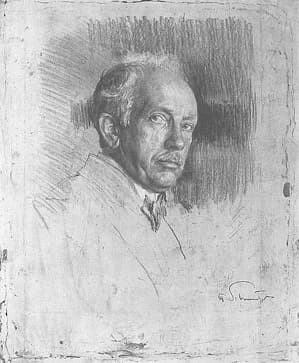

Arutiunian dedicated his tuba concerto to the American tuba virtuoso Roger Bobo (1938–2023). Considered the leading tubist in the world at the height of his fame, his recordings of both serious concertos and humorous works brought the tuba to the forefront, leading to the first solo tuba recital at Carnegie Recital Hall in 1961. One of his humorous pieces was Effie the Elephant, composed by Alex Wilder. It closes with the irrepressible Effie joining the carnival.

Alec Wilder: Suite No. 1, “Effie Suite” (version for tuba and piano) – IV. Effie Joins a Carnival (Roger Bobo, tuba; Ralph Grierson, cond.)

Bobo said once that he saw the role of the tuba like that of the mythological character Sisyphus, condemned forever to roll a rock up a hill, only to have it return to the bottom again. Bobo’s colleague John Stevens wrote The Liberation of Sisyphus for solo tuba and tuba octet, with the solo tuba in the title role. The piece is in three parts: first, Sisyphus and his never-ending task, second, the liberating of Sisyphus, and third, the actual liberation.

John D. Stevens: Liberation of Sisyphus (Roger Bobo, tuba; European Tuba Octet; John D. Stevens, cond.)

Supportive or serious, dancing or funny, the tuba always commands our attention. Each of these composers approached the instrument as either one of their favourites or as an instrument that they felt had greater possibilities than had yet been made into music. Next time you watch a concert, take your eyes off the violins and focus on the back right, and see what the tuba is up to!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter