John Williams

I’ve never made a secret of the fact that John Williams is my favourite film composer. With over 100 film scores to his credit, he has composed some of the most popular, recognizable and critically acclaimed film scores in cinematic history. I am sure you remember “Jaws”, “Indiana Jones”, “Harry Potter”, “Jurassic Park” and “Star War” series alongside films like “Schindler’s List”, “Superman”, “War of the Worlds”, and “The Terminal”, to only name a few. In his brilliant film scores, Williams employs a series of themes and motifs that represent the various characters, objects and events in the film, akin to the system of leitmotifs employed in the music dramas of Richard Wagner. For his musical efforts, William has received 5 Academy Awards, 18 Grammys, 3 Golden Globes, 2 Emmys and numerous gold and platinum records.

John Williams and Steven Spielberg

And while Williams has maintained a steady output of quality film scores, he has also composed numerous pieces for the concert hall, including a symphony and concertos for various instruments. To be honest, I was initially really surprised when I listened to his concert music. I had expected lush and memorable tunes and motifs, but instead found a broad lyricism that seemed to evolve slowly and organically. A critic writes, “as a composer of concert music, Williams has enriched both the symphonic and concerto forms, writing a significant number of great works performed by major orchestras and soloists throughout the world.” To me that sounded like an open invitation to explore in a bit more detail the musical side of John Williams that is generally not as well known.

John Williams: Violin Concerto (Gil Shaham, violin; Boston Symphony Orchestra; John Williams, cond.)

John Williams and Barbara Ruick

In March 1974, John Williams suffered the devastating and sudden death of his wife Barbara Ruick-Williams. And while he quickly became one of the most sought-after composers in Hollywood, he recalls being “in a state of shock that year and the year after, so when all of these accolades were going on, I was barely aware of it.” As Williams later disclosed, “When I was about 40 years old, I lost somebody very, very, very close to me unexpectedly, and before that point in my life, I didn’t know what I was doing. But after that point in my writing, in my approach to music, and everything that I was doing, I felt clear about what it is I was trying to do… It was a huge emotional turning point in my life but one that resonates with me still, and taught me about who I was and what I was doing, and what it meant. This is a deeply emotional thing, and in a way, that was the greatest gift ever given to me – if I can put it that way – by anyone. And certainly, a pivotal moment in my thinking, in my living of my life, and approaching the blank page absolutely. I immediately knew where to go with this emotionally.”

John Williams with Gil Shaham and Stéphane Denève © Hilary Scott

In response to his wife’s death, Williams composed his most intensely personal work, his Violin Concerto. The composition of the concerto took Williams the better part of two and a half years, and it premiered in St. Louis in 1981. Critical reviews were universally hostile as he was seen to have “written an academic and imitative concerto, lacking an overall design or purpose. It merely pushes buttons for alternating currents, lean, drifting lyricism versus vehement agitation.” A different critic wrote, “Much ado about nothing. And of course, it does not contain a single memorable theme.” It took until the late 1980 before the artistic value of the work was recognized, and it found its highest-profile champion in violinist Gil Shaham.

John Williams: Tuba Concerto (Øystein Baadsvik, tuba; Singapore Symphony Orchestra; Anne Manson, cond.)

While his Violin Concerto was “forged in a crucible of grief, it also marked a point of stylistic introspection,” which Williams described as “the closest I’ve been able to come to a genuine, idiosyncratic expression.” It took Williams nine years to tackle his next concerto, and the Tuba Concerto is perhaps the one that sounds closest to his film music.

Chester Schmitz

Williams was the conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra between 1980 and 1993, and it was during this time that he composed his Tuba Concerto. It was commissioned to celebrate the orchestra’s centenary in 1985, and it is dedicated to the orchestra’s solo tuba player, Chester Schmitz. Williams writes, “I really don’t know why I wrote it—just urge and instinct. I’ve always liked the tuba and even used to play it a little. I wrote a big tuba solo for a Dick Van Dyke movie called “Fitzwilly” and ever since I’ve kept composing for it—it’s such an agile instrument, like a huge cornet. I’ve also put passages in for some of my pets in the orchestra—solos for the flute and English horn, for the horn quartet and a trio of trumpets. It’s light and tuneful and I hope it has enough events in it to make it fun.” However, as a critic wrote, the Tuba Concerto is not very easily pigeonholed…

One is never sure what might emerge from the shadows in the nocturnal central Andante, for instance, and although the finale’s fanfares create a festive air initially, that sense of something possibly malevolent lurking in the dark corners remains to the end.

John Williams: Cello Concerto (Yo-Yo Ma, cello; Los Angeles Recording Arts Orchestra; John Williams, cond.)

John Williams with Yo-Yo Ma © Lawrence Sumulong

The film music of John Williams is rooted in tonality, tradition, and an unbelievable gift for writing elegant and memorable melodies. In his concert music, however, he is not afraid to freely use modern techniques like atonality and an occasional 12-note series. As a scholar writes, “In both worlds Williams is the same composer, a sure and rigorous craftsman first wherever he is working, guided by a precision of purpose, balanced by inspiration and taste.” John Williams met Yo-Yo Ma during his days with the Boston Pops. Over the decades they have become musical institutions in their own rights. “Their camaraderie might be a metaphor for the enduring relationship they enjoy. Individually and together, Ma and Williams transcend the hard choices—pop versus classical, art versus entertainment, serious versus fun—that tend to define music in this age. From their first encounters, each recognized in the other an understanding that, as Williams simply puts it, “music is our oxygen.”

Williams remembers, “I’d already learned about this wunderkind who played cello, and was very excited to meet him when he came to the Boston Pops for one of our television recordings. I was enormously impressed with this fantastically mature art from such a young person.” Williams composed the Cello Concerto expressly for Ma, trying to capture the many personalities of the young cellist. In fact, “the four very distinctive movements even run together as if to pause would be to break the spell, to lose the impetus. The opening brass fanfare introduces the soloist, and the solo cadenza “transports us into a more exotic place where clusters of piano and metallic percussion frame a kind of oriental blues.” You remember me talking about the broad singing lyricism that permeates much of Williams’ concert music? You have to look no further than the final movement called “Song.”

John Williams: Bassoon Concerto, “The Five Sacred Trees” (Robert Williams, bassoon; Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

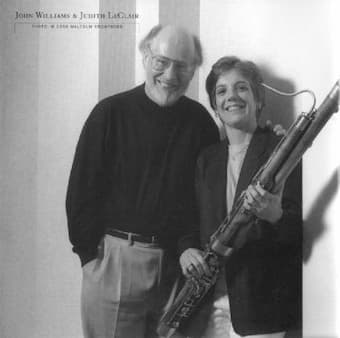

John Williams and Judith LeClair

John Williams composed his Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra, subtitled “The Five Sacred Trees” on commission from the New York Philharmonic on the occasion of its 150th anniversary and for its principal bassoonist, Judith Le Clair. In the preface to the score Williams writes, “As we become increasingly aware of the damage done by the destruction of our forests, it is illuminating to discover that our ancestors, many thousands of years ago, prayed to the spirits before felling a tree. One prayer was appropriate for a maple, another for the elm, the ash, and so on. The English poet Robert Graves writes of these prayers, which I have been unable to find, but which nonetheless have moved me to compose this music featuring the bassoon, itself a tree.” Each movement represents a particular tree, and Williams took his musical inspiration from the “uilleann pipes” of Irish music, which he considers the ancestor of the bassoon. As the composer writes, “The Celtic flavor of the concerto seemed very appropriate, as the instrument is haunted by the spirit of the wood. A concerto based on the five sacred trees of Celtic mythology seemed to be a good way of combining my thoughts on both music and mythology.”

The first movement is entitled “Eó Mugna,” the great oak “whose roots extend to the otherworld as it stands guard over the source of the River Shannan and is the font of all wisdom.” Of the following “Tortan” movement, Williams writes, “Tortan is a tree that has been associated with witches and as a result, the fiddle appears, sawing away, as it is conjoined with the music of the bassoon.” The lyrical third movement is titled “Eó Rossa,” and describes a yew tree, “often referred to as a symbol of death and destruction.” “Craeb Uisnig” is an ash, and it has been described as a source of strife. “Thus,” according to the composer, “a ghostly battle, where all that is heard as the phantoms struggle, is the snapping of twigs on the forest floor.” The concluding fifth movement is titled “Dathi” and “purportedly exercised authority over the poet, and was the last tree to fall. The bassoon soliloquizes as it ponders the secrets of the Trees.”

John Williams: Prelude and Fugue (The President’s Own United States Marine Band; Michael J. Colburn, cond.)

The young John Williams

I was very interested to learn that John Williams’ initial musical background was in Jazz. His father, Johnny Williams was a jazz drummer and percussionist who played with the bandleader Raymond Scott. After his family moved to Los Angeles, young John studied with the pianist and arranger Bobby Van Eps. He orchestrated for and conducted service bands during his stint with the US Air Force, then moved back to New York to study with Rosina Lhévinne at the Juilliard School. He played in jazz clubs and recording studies, and after his return to the West coast enrolled at UCLA. He took private composition studies with Arthur Olaf Andersen and Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, and started his career as a studio pianist in Hollywood, arranging and composing music for television. In 1965 Williams composed a Prelude and Fugue for Stan Kenton’s Los Angeles Neophonic Orchestra. While the “Prelude” seems “allied with other experimental new music of its time,” the “Fugue” sounds his jazz expertise as “the brass and woodwind slither and strut in a manner that’s redolent of noir detective television programmes.”

John Williams: Horn Concerto (Karl Pituch, horn; Detroit Symphony Orcehstra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

Dale Clevenger

John Williams composed his Horn Concerto for the principal horn player Dale Clevenger of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The work premiered on 29 November 2003, and a critic noted that the “five movements come with descriptive titles that suggest scenes from an unseen movie for which the solo horn and the orchestra provide color and mood.” Since Williams composed the work in the middle of writing music for the third Harry Potter movie, it is a valid point. However, the inspiration seems to go a lot deeper. As Williams writes, “When I’ve tried to analyze my lifelong love of the French horn, I’ve had to conclude that it’s mainly because of the horn’s capacity to stir memories of antiquity. The very sound of the French horn conjures images stored in the collective psyche. It’s an instrument that invites us to dream backward to the ancient time… The horn stirs memories of fearful things, of powerful things, of noble and beautiful things!” Williams included a poetic quote for each movement of the concerto, “none of which is medieval, but simply chosen from writers that I’ve enjoyed, and in the music I have not deliberately adhered to, or purposely avoided, the modalities and grammar of medievalism.”

John Williams with Anne-Sophie Mutter © David Noel Edwards

The vast majority of John Williams’ concertos are the result of decades long collaboration and friendship with some of the world’s most celebrated musical artists. And this is certainly the case with his Violin Concerto No. 2, commissioned by Anne-Sophie Mutter. Mutter had long admired the composer’s deep love for her instrument, and the initial point of contact was the lyrical Markings for solo violin, strings, and harp, which Mutter premiered in July 2017. Williams considers his 2nd Violin Concerto to be “about Anne-Sophie Mutter, and the violin itself. With so much great music already written for the instrument, much of it recently for Anne-Sophie, I wondered what further contribution I could possibly make. But I took my inspiration and energy directly from this great artist herself. We’d recently collaborated on an album of film music for which she recorded the theme from “Cinderella Liberty,” demonstrating a surprising and remarkable feeling for jazz. So, after a short introduction, I opened the “Prologue” of this concerto with a quasi-improvisation, suggesting her evident affinity for this idiom. There is also much faster music in this movement, and while writing it, I recalled Anne-Sophie’s particular flair for an infectious rhythmic swagger.” For a number of commentators, the Second Violin Concerto “finds its elegiac splendor sublimely poignant, and it is his crowning achievement to date.” Mutter writes, “The ending is very personal, almost private and I find it such an honest and purely poetic way to conclude a work that also deals with great drama, sarcasm and wit.” Writing this blog has been such an educational experience for me, as I have started to learn and appreciate the incredible musical and compositional versatility of John Williams; I hope you have liked this little survey as well, and I invite you to keep exploring his other concert scores as well.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

John Williams: Violin Concerto No. 2 (Anne-Sophie Mutter, violin; Boston Symphony Orchestra; John Williams, cond.)

I am amazed that John Williams’ classical compositions are not recorded. I would love to hear more of this genre of his music. He is so much more than a composer of film and tv music.