Recently, the “Centre de musique romantique française” at the Venetian Palazzetto Bru Zane has released an impressive anthology of 165 compositions by French Romantic women composers. In essence, they have resurrected the memory of nineteenth-century French women composers that had been completely lost. Recent research and recording projects have made it possible to rediscover them.

The garden and the entrance to the palazzetto Bru Zane

The project description reads as follows, “These undertakings have made it possible to highlight the fact that, despite the social pressures exerted on women of this period (first and foremost marriage and motherhood), which represented many obstacles to a career as a composer, a quantitatively and qualitatively important corpus of works by women composers survives.” Les Femmes “Compositeurs” generally were representatives of the social elite, and confined to their homes. A scholar writes, “The fact that they were prevented from becoming professionals naturally prompted women composers to steer clear of the most prestigious musical venues—the opera houses and symphony concerts—and content themselves with intimate spaces.”

In this blog, let us explore the music of this intimate space in the form of chamber music. Time to get started with a beautiful sonata for cello and piano by Henriette Renié.

Henriette Renié: Sonate pour violoncelle et piano

Henriette Renié

Henriette Renié: Sonate pour violoncelle et piano (Victor Julien-Laferrière, cello; Théo Fouchenneret, piano)

Once again, I have to confess that I had never heard of Henriette Renié (1875-1956) before stumbling on the Palazzetto Bru Zane anthology of recordings. She was the daughter of a singer who studied with Rossini, and “discovered the instrument that was to make her famous at a concert given by Alphonse Hasselmans in Nice.” That instrument in question was the harp, and her father even invented extensions to help her reach the pedals when she was only eight. She quickly gained admission to the class of Hasselmans at the Paris Conservatoire, “and was unanimously awarded the Premier Prix for harp at the age of eleven.” With special permission, she was allowed to take theory classes at the age of thirteen, and she took lessons with Théodore Dubois (harmony), and then Charles Lenepveu (counterpoint and fugue). Renié became a celebrated concert harpist, founded an international harp competition, and even wrote a treatise on her favorite instrument. Her compositions are almost exclusively written for the harp, with the exception of the Sonata for cello and piano.

Renié’s Cello Sonata was apparently first performed at a concert given by the Société nationale de musique at the Salle Pleyel on 15 February 1896. In accordance with the conventions of the time, Renié presented her composition under the guise of having been written by a man. A critic wrote, “Success for the Sonata by a new musician, J. Renié, performed by a pianist with no weakness and a cellist with no strength.” Critics did praise the score, but the music was considered monotonous. It was only published in 1920 after it had won the prestigious Prix Chartier awarded by the Institute de France. The sonata borrows a quotation from César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A major, “and Renié uses the cyclic technique, making its initial theme, with its strong chromatic modulations, the matrix of the entire musical discourse.”

Mélanie Bonis: Cello Sonata in F Major, Op. 67

Mélanie Bonis

Mélanie Bonis: Cello Sonata in F Major, Op. 67 (Victor Julien-Laferrière, cello; Théo Fouchenneret, piano)

Let us continue to sample compositions for cello and piano by Les Femmes “Compositeurs”. We already met Mélanie Bonis (1858-1937) in my blog on orchestral compositions by French Romantic Women Composers. She was such a prolific composer that it is probably not surprising that she also composed lots of chamber music. Her Cello Sonata, Op. 67 is dedicated to the author and critic Maurice Demaison, and dates from 1904. As the liner notes tell us, “it belongs to the corpus of works composed during the artist’s great creative period, after the abandonment of her illegitimate daughter and before the First World War when, in her own salon or on prestigious stages, she presented a series of new pieces reflecting the productions of her time.” Inspired by the works of César Franck, the Cello Sonata first sounded on 14 February 1906 at the Salle Pleyel. The work was received with praise, with a critic finding “a captivating sound, written in the manner of Schumann in the second movement, which shows a very personal sincerity and a noble sentiment, without making any unnecessary concessions, which is to the author’s great credit.”

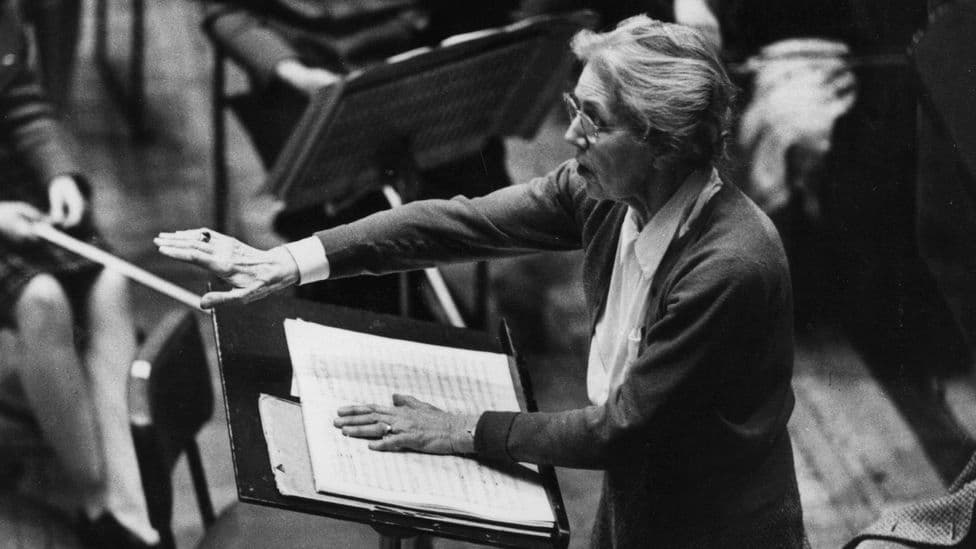

Nadia Boulanger: Trois Pièces pour violoncelle et piano

Nadia Boulanger

Nadia Boulanger: Trois Pièces pour violoncelle et piano (Victor Julien-Laferrière, cello; Théo Fouchenneret, piano)

I think that everybody in the musical world knows the name Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979). For some historians, “as far as musical pedagogy is concerned, and by extension of musical creation, she is the most influential person who ever lived.” The famous American composer Aaron Copland writes, “I shall count our meeting the most important of my musical life. Whatever I have accomplished is intimately associated in my mind with those early years, and with what you have since been as inspiration and example.” We should not forget that besides being one of the most famous pedagogues of all time, Boulanger was the first woman to conduct major orchestras in America and Europe. And of course, she was a highly versatile composer. She studied with Gabriel Fauré at the Paris Conservatoire, and her works include over 30 songs, chamber music, and a Fantasy for piano and orchestra. She stopped composing in the early 1920s to follow her pedagogical calling, but her compositional legacy does include the delightful 3 pieces for cello and piano.

Igor Stravinsky and Nadia Boulanger in 1937

The 3 Pieces were originally written for organ in 1911, but her version for cello and piano has been much more popular. In the original manuscript, the first piece was called “Improvisation,” the second “Prélude,” and the third “Danse espagnole.” The liner notes inform us “the cello-piano version brings out more clearly the connection between these pieces and the works of Nadia Boulanger’s composition teacher at the Conservatoire. The serene expressiveness of the first piece, the gentle melancholy of the second, and the mischievousness of no. 3 call to mind the chamber music of Gabriel Fauré. They also make us regret that the composer did not explore this field a little more.” Frequently described as post-impressionist, the opening piece is a mysterious Moderato, the second resembles a peaceful lament, and the concluding piece “is an edgy almost frantic affair resembling the hurly-burly of modern life.”

Lili Boulanger: 2 Pieces for Violin and Piano

Lili Boulanger

Lili Boulanger: 2 Pieces for Violin and Piano (Anna Agafia, violin; Frank Braley, piano)

We’ve already met Nadia’s sister Lili Boulanger (1893-1918) in our previous blog on orchestral compositions by French Romantic Women Composers. The Palazzetto Bru Zane recordings present 2 Pieces for Violin and Piano that were not intended as a set nor originally scored for violin. The first piece “Nocturne” originated at the Conservatoire as an assignment in Boulanger’s counterpoint and fugue class with Georges Caussade and her composition class with Paul Vidal. It dates from 1911 and was simply titled “Short Piece,” and scored for flute and piano accompaniment. As you can hear, it evokes the harmonic subtlety of Gabriel Fauré, and after the composer’s death, the publisher Ricordi titled it “Nocturne,” mentioning the violin as a suitable alternate. The second piece titled “Cortège” was composed after Boulanger returned from Rome in July 1914. Originally it was conceived as a piano piece, but an alternative version for violin (or flute) and piano appeared soon thereafter. The line notes tell us that “the cortège of the title refers to a procession, but not an austere religious one, as we might expect: here it appears to take place in a country setting in spring, and it follows an unrelenting pace which even gathers speed.”

Rita Strohl: Grande fantasisie-quintette

Rita Strohl

Rita Strohl: Grande fantasisie-quintette (Ismaël Margain, piano; Quatuor Hanson)

Rita Strohl (1865-1941) showed impressive musical aptitude at an early age, and she was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire at the age of thirteen. Her compositions were first heard in public in Paris, and subsequently in Rennes and Chartres. As the liner notes for the Palazzetto Bru Zane explain, “Her works, showing a propensity for mysticism, and combine various religious inspirations. Strohl’s Hindu and Celtic operas are imbued with different forms of spirituality, while others display traces of pantheism.” She was strongly influenced by Symbolist theories, and “her sometimes esoteric experiments and her taste for mystery appear in her prefaces in the annotations of her scores.” In fact, she created the short-lived La Grange Theatre in Bièvres, Essonne in 1912 with her second husband and with the financial support of Odilon Redon, Gustave Fayet and other subscribers, where she performed lyrical works filled with mysticism and symbolism.”

Rita Strohl

Rita Strohl’s highly creative and individual personality also spawned a “Fantaisie-Quintette” that seems to break all the rules and conventions. The composition dates from the early years of her career, “and this readily dramatic piece progresses without any clear formal structure; instead, scattered ideas are developed harmonically or melodically.

The treatment of the instrumental ensemble also diverges from current norms: rather than seeking a balance between the instruments, Strohl favours the piano part, thereby giving the score the appearance of a concerto, with the string quartet providing a regular homorhythmic accompaniment.” The “Fantaisie-Quintette” was never published, but it was performed during her lifetime. What a fascinating composition and composer, and I will certainly explore her works in more detail.

Clémence de Grandval: Andante and Intermezzo

Clémence de Grandval

Clémence de Grandval: Andante and Intermezzo (Alexandre Pascal, violin; Héloïse Luzzati, cello; Célia Oneto Bensaid, piano)

Clémence de Grandval (1828-1907) is another composer completely unknown to me. She was the daughter of aristocratic parents, her mother was an amateur pianist, and her father a writer. Growing up in a chateau in the Sarthe département, she apparently received piano lessons from the German composer Friedrich von Flotow, and also met Frédéric Chopin, “who was to remain a constant source of inspiration for her.” She studied composition with Camille Saint-Saëns and “made a considerable name for herself as a composer.” Grandval had a number of compositions published, and her religious works entered the repertory of many churches. She also composed a number of operas and an oratorio, and during the 1870s, she took an interest in instrumental music. The performance of her Oboe Concerto Op. 7 at the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire was a great success, and she received the Prix Chartier in 1890 for her entire chamber music output.

Grandval’s two movements for piano trio are dedicated to the violinist Édouard Nadaud. First published in 1889 by Bruneau, the premiere apparently took place on 15 February 1890 at the Salle Pleyel, with Marie Jaëll (piano), Léon Heymann (violin) and Cornélis Liégeois (cello). A contemporary critic called the work “very weak,” but it enjoyed some popularity in the musical salons. Since the two movements make only moderate demands on the performers, they are accessible to amateur musicians. “The Andante (initially marked “expressivo”) plays essentially on rhythmic oppositions between the piano and the other two soloists, while the Intermezzo begins with a musical discussion between violin and the cello, punctuated by an ostinato rhythm in the piano.”

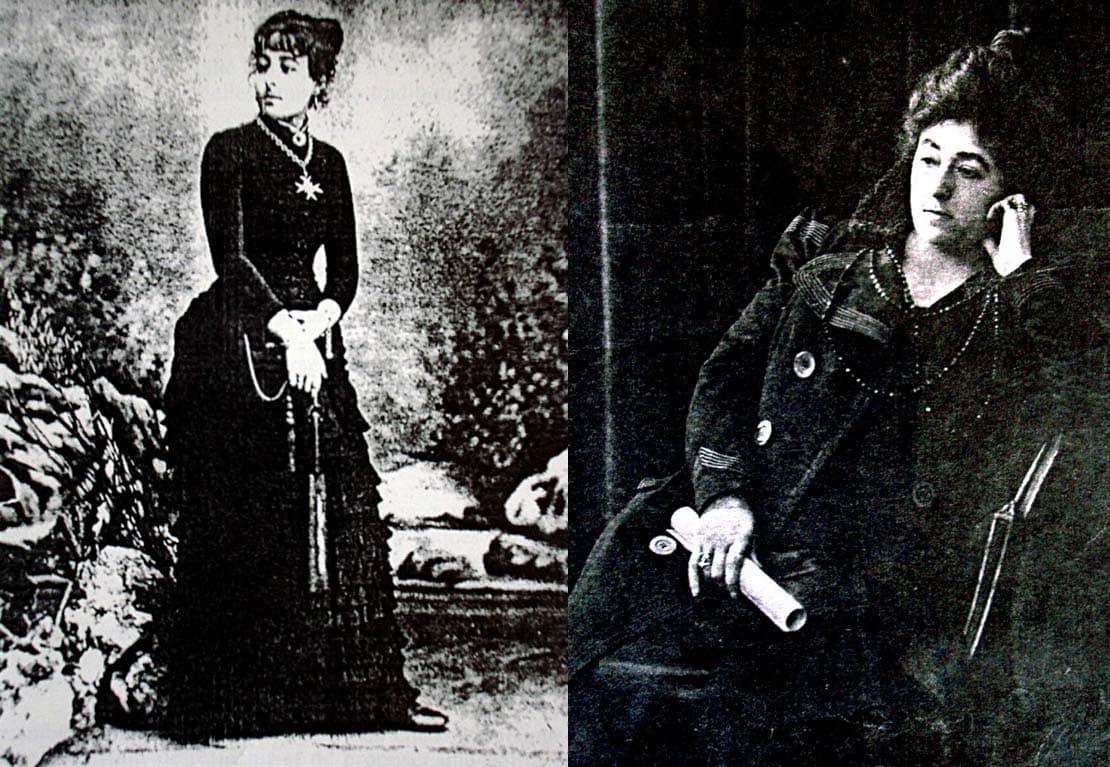

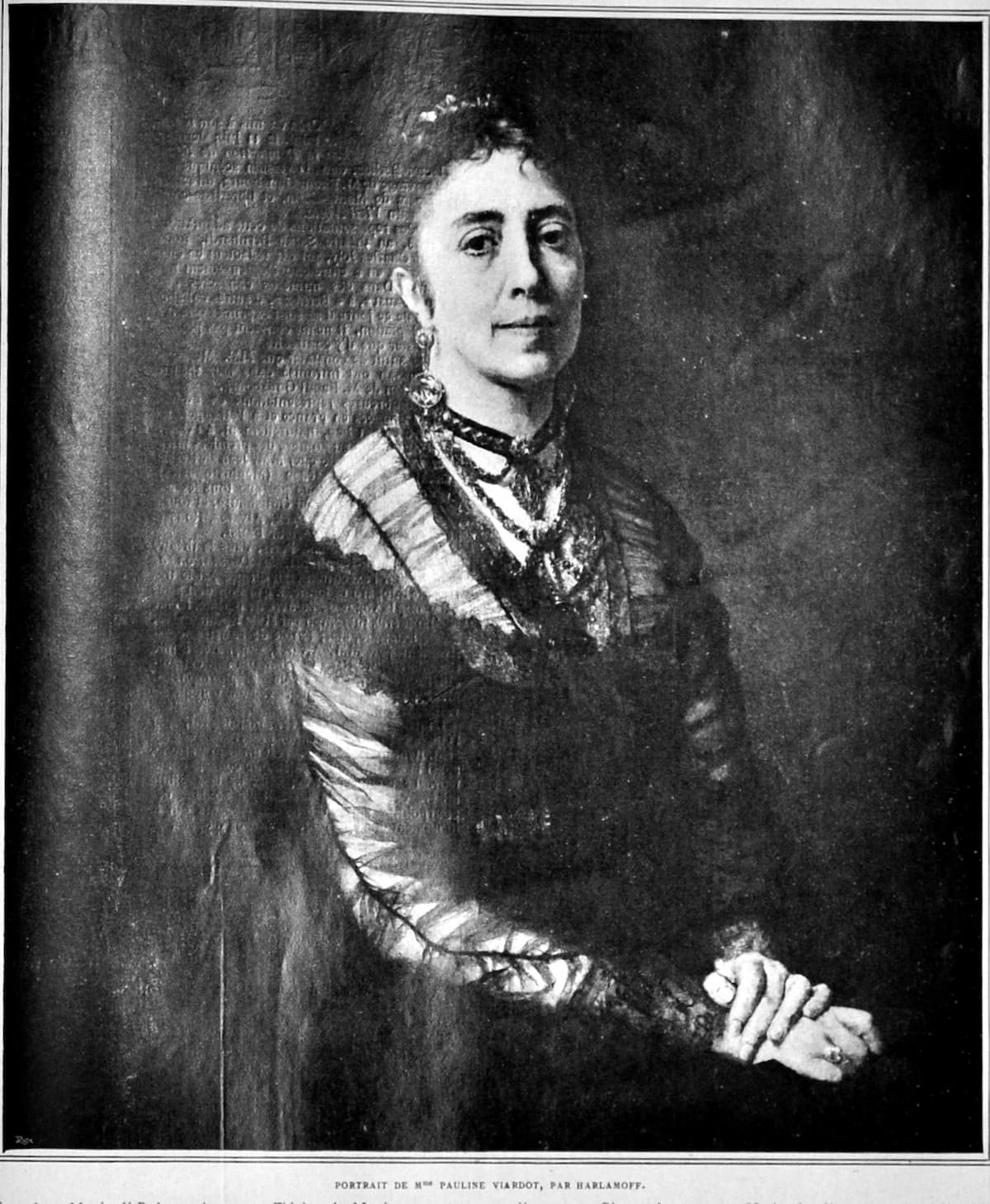

Pauline Garcia-Viardot: Violin Sonatine in A minor, VWV 3005

Pauline Viardot in 1910

Pauline Garcia-Viardot: Violin Sonatine in A minor, VWV 3005 (Anna Agafia, violin; Frank Braley, piano)

Pauline Garcia-Viardot (1821-1910), sister of Maria Malibran, studied piano and voice with her father and later took composition lessons with the famed Czech composer and performer Antoine (Anton) Reicha. Viardot was held in the highest esteem as a pianist, and her artistic salons in Paris and Baden-Baden, launched the careers of Camille Saint-Säens, Jules Massenet, Gabriel Fauré, and Charles Gounod. She did not regard herself as a composer, as she considered her compositional activities “as a mode of communication and mediation: communication between amateurs and professionals, between different stylistic orientations and levels, between different musical cultures.” She worked closely with publishing houses in France, Germany, and Russia, and her compositions achieved considerable popularity. The Violin Sonatine was probably first performed by Viardot and her son Paul on 21 March 1874 at the National Society of Music. Scored in three movements, Viardot easily transferred her talents for melodic and lyrical writing into the instrumental domain.

Louise Farrenc: Piano Trio in E minor, Op. 45

Louise Farrenc

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875), whom we have already met earlier, was an exceptional pianist. As a composer, her piano parts were greatly admired “for a simplicity of style and delicacy of touch.” When her Trio Op. 45 premiered on 7 December 1856, a critic wrote, “What delicacy in the choice of harmonies! What spontaneity in the developments! It is everywhere an exquisite freshness, a young and flourishing feeling, an overflowing expansion: one would say the work of Mozart at twenty.” It is certainly a striking work, which enjoys deserved fame. Dedicated to the flautist Louis Dorus, it was published at the author’s expense five years later. The liner notes suggest that the opening “Allegro” seems to race a path from deep sadness to hope. The singing flute comes to the foreground in the “Andante,” while the Scherzo propels the listener into a pastoral atmosphere. In the “Finale,” the virtuosity of the performers is at the service of a perfect ensemble. According to the publisher, the violin may substitute for the violin. Please join me next time when I survey music for the most popular instruments of Les Femmes “Compositeurs”, the piano.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Louise Farrenc: Piano Trio in E minor, Op. 45 (Alexandre Pascal, violin; Héloïse Luzzati, cello; Célia Oneto Bensaid, piano)