“I do not bow to anyone, except to my own conscience and our own noble Lady Music”

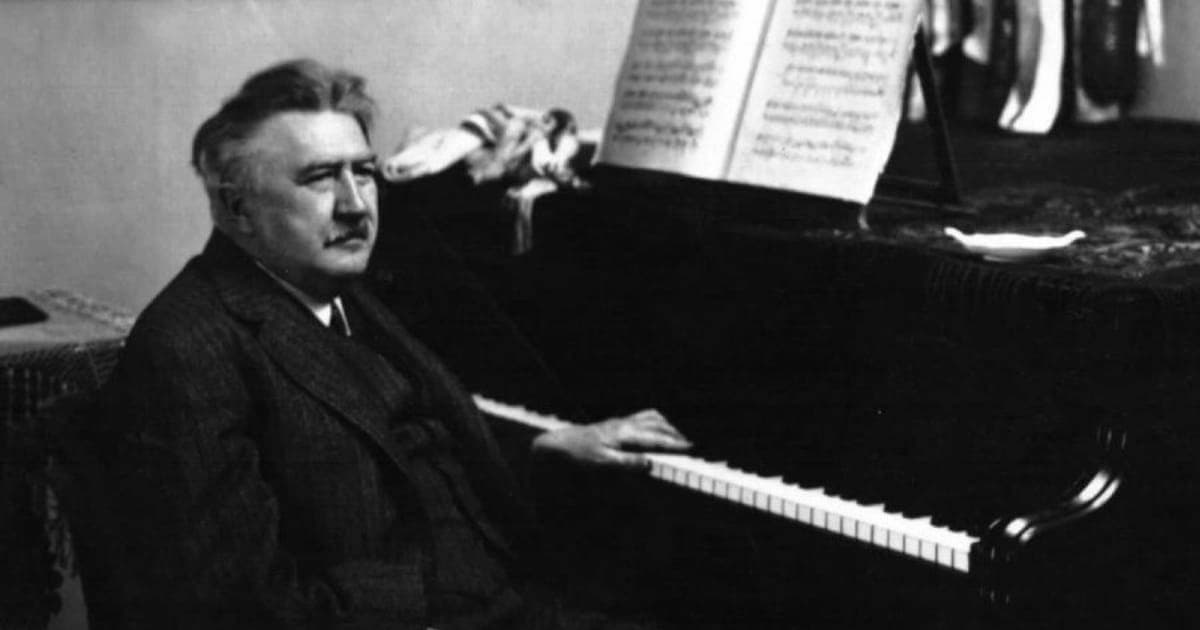

Josef Suk

January is a busy time for lovers of classical music as we celebrate the birthdays of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Franz Schubert on 27 and 31 January, respectively. And while these two giants are subject to annual celebrations, a good number of highly talented and wonderful composers were also born in January. It just so happens that we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Czech composer and violinist Josef Suk in January 2024.

In the great dictionaries of famous composers, Josef Suk seems more of a footnote, but he was the favourite student of Antonín Dvořák. Mind you, he was also his son-in-law as he married Dvořák’s daughter Otilie in 1898. We know that Gustav Mahler and Alban Berg admired Suk’s music, and with the blessing of Johannes Brahms, he was regarded as the leading composer of the modern Czech school.

Josef Suk: Piano Quartet in A minor, Op. 1

Bohemian Roots

Suk never reached the popularity enjoyed by his compatriots Leoš Janáček and Bohuslav Martinů. And there is a simple reason for that. Unlike his more revolutionary compatriots, Suk never broke away from the chromatic style of the late nineteenth century but instead embraced the musical language of Liszt and Wager and advanced them in a highly personal and intimate musical language.

Suk came from a long line of Bohemian musicians and choirmasters. His father trained him in playing the organ and the piano, and he received advanced violin training from Antonín Bennewitz after his entry to the Prague Conservatory. He received a thorough grounding in music theory, but most importantly, he studied chamber music with Hanuš Wihan and subsequently composition with Antonín Dvořák.

Josef Suk: Serenade for Strings in E-flat Major, Op. 6

Czech Quartet

Josef Suk graduated from the conservatory in 1891 and submitted his Piano Quartet Op. 1 for examination. The work gained him an extra year at the conservatory for special tuition in chamber music and composition, and he started playing second violin in a group under Wihan, which in 1892 became known as the “Czech Quartet.” The quartet performed in Vienna in January 1893, and the critic Eduard Hanslick, Brahms, and Brucker were present.

The Czech Quartet

The Vienna performance proved a major turning point that established their international reputation, and the “Czech Quartet” gave more than 4,000 concerts until Suk’s retirement in 1933. As you can tell, Suk was an outstanding violinist, and he did perform as a soloist, but he felt really at home in a chamber setting. Apparently, Suk did not spend much time practicing individual pieces; “all he needed before a performance was a quick warm-up.”

Josef Suk: String Quartet No. 1 in B-flat Major, Op. 11 (The Suk Quartet)

Early Success

The “Czech Quartet” naturally focused on works by Smetana and Dvořák, sprinkled with literature from the standard eighteenth and nineteenth-century chamber literature. In addition, they performed contemporary works by Debussy, Ravel, Milhaud, Schoenberg, Janáček, and Suk himself. It was the great pianist Artur Schnabel who remembered the quartet as “four fascinating men, a wonderful blend of great simplicity and great vitality, and they were also superb players.”

Suk enjoyed early successes as a composer, and a contemporary musicologist writes, “I know of very few string quartets since the time of Brahms which do justice to the style of the artistic form with such certainty as this work of the remarkable second violinist of the ‘Bohemians’.” Yet despite his opportunities through his constant travels as a performer to hear and perform the latest European novelties, he was subject to no other strong musical influence.

Josef Suk: 8 Piano Pieces, Op. 12 (Pavel Štěpán, piano)

Courtship…

Otilie

In the summer of 1892, Josef Suk fell in love with Otilie, affectionately called Otilka, the fourteen-year-old daughter of Antonín Dvořák. Apparently, Dvořák was the last one to notice the blossoming romance, but his wife Anna was strictly against the relationship. Not merely on account that her daughter was rather young, but she was also looking for someone with a much more stable profession.

Otilie was a highly gifted musician, an exceptional pianist, and an aspiring composer. As Suk reports, “Once, after my return from travelling, Otilie confessed to me that she had composed several “little pieces for piano.” Initially, she felt embarrassed to play them for me but when I finally persuaded her to play, it caused her great joy when, during her second play-through, I stood up with a pencil in my hand and wrote down everything just as I had heard her play it. She clapped her hands and laughed a great deal when I advised her on something, and she was very surprised it had not occurred to her.”

Otilie Suková-Dvořáková: “Humoresque” (Tomáš Víšek, piano)

… and Tragedy

Otilie and her son Josef

On 7 November 1898, the day of Dvořáks’ silver anniversary, Josef and Otilka got married. Three years later their only son Josef was born. However, during her pregnancy Otilka was diagnosed with a serious heart condition. Concurrently, Dvořák had been forced by illness to “take to his bed,” and he suffered for five weeks under an “attack of influenza.” Dvořák died on 1 May 1904, and his funeral service was held on 5 May in in Vyšehrad Cemetery in Prague.

Suk was devastated by Dvořák’s death, and Otilka’s condition also significantly worsened after her father’s passing. She suffered a fatal heart attack and passed away on 5 July 1905,

at the unspeakable young age of twenty-seven. The loss of his wife and father-in-law deeply affected Suk’s life and subsequent compositions. He never remarried but remained true to the memory of his wife. The 8 Piano Pieces, Op. 12 are dedicated to Otilka, and the always popular Love Song Op. 7 became a symbol of his love.

Josef Suk: “Song of Love,” Op. 7

A New Beginning

Already before the turn of the century, Suk realised that his emulation of his teacher would eventually result in an artistic dead end. It is within the incidental music for the play “Radúz and Mahulena” that his own steady and organic development moved towards a complex polytonal musical language. Suk made note of the work’s impact upon his compositional style, writing “I admit that I found myself in the music for Radúz a Mahulena, and that this work impacted my compositions for many years.”

“Until later,” he wrote, “I had no idea that the motives of love and death found in the music of Radúz would accompany my artistic growth from the beginning until the end.” While the music of this period is exuberantly happy, the personal tragedy strongly influenced his music after 1905. As he sought spiritual and artistic ways of coping with his loss, his language became infused with both a metaphysical expressiveness and a very complex chromatic language.

Josef Suk: “Fairy Tale,” Op. 16 (Suite from Radúz and Mahulena) (Prague Symphony Orchestra; Jiří Bělohlávek, cond.)

Asrael

Josef Suk’s greatest achievement lays in orchestral music, and the promise shown in Radúz was followed by the Violin Fantasy and the Straussian tone poem Praga. The death of his father-in-law and his wife had shattered the composer’s life and attitudes, and it set into motion the Asrael Symphony, Op. 27. Titled after the angel of death in the Old Testament and as the Islamic carrier of souls after death, the work originally was to sound a celebratory remembrance of Dvořák’s life and work.

However, the optimistic tone quickly disappeared, and Suk writes, “The fearsome Angel of Death struck with his scythe a second time. Such a misfortune either destroys a man or brings to the surface all the powers dormant in him. Music saved me, and after a year I began the second part of the symphony, beginning with an adagio, a tender portrait of Otilka.” Asrael is arguable Suk’s greatest works “and one of the finest and most eloquent pieces of orchestral music of its time, comparable with Mahler in its structural mastery and emotional impact.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Thank you for this tribute to Suk. The great Rudolf Serkin, when he was yet a teenager, performed Suk’s Op. 30 piano set, Life and Dream, in Vienna in April 1919. This was part of a series of private concerts overseen by Arnold Schoenberg.