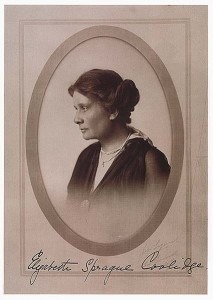

If you are passionate about the chamber music of the twentieth century, chances are that the works are due to Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge (1864-1953) — one of the most notable patrons of our time. Without her vision we would not have the numerous chamber music masterworks she commissioned or the Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium where wonderful programs are performed to this day. The composers she supported read like a who’s who list—Bartók, Barber, Britten, Copland, Ravel, Prokofiev, Stravinsky and many other towering figures of the time. A distant cousin of President Calvin Coolidge, she was sometimes misidentified as his wife, and called the “other Mrs. Coolidge” in jest.

If you are passionate about the chamber music of the twentieth century, chances are that the works are due to Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge (1864-1953) — one of the most notable patrons of our time. Without her vision we would not have the numerous chamber music masterworks she commissioned or the Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium where wonderful programs are performed to this day. The composers she supported read like a who’s who list—Bartók, Barber, Britten, Copland, Ravel, Prokofiev, Stravinsky and many other towering figures of the time. A distant cousin of President Calvin Coolidge, she was sometimes misidentified as his wife, and called the “other Mrs. Coolidge” in jest.

Elizabeth Sprague’s musical nurturing began early. She studied piano and composition with eminent teachers. When she was seventeen she and her parents embarked on an extended trip to take in the sights and sounds of the major concert halls of Europe including Paris’ Théâtre de l’Opéra and Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival in Germany. By then she was a striking woman at just over six feet tall, and according to the Library of Congress archives, “forehead high; eyes blue; nose straight; chin pointed; hair light; complexion light; face oval.”

Elizabeth was twenty-seven years old when she married physician Frederick Shurtleff Coolidge in 1891—a progressive man, who encouraged her performing and composing. Elizabeth continued her salon evenings and programs for charity. She composed a string quartet, and in honor of her tenth wedding anniversary, a song cycle to the text of Sonnets from the Portuguese by Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

Tragically Elizabeth’s husband and parents passed away in quick succession. To honor her father she initiated a pension fund for the musicians of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, of which her father was a patron.

Mrs. Coolidge was a skillful musician who craved collaborations with other performers. In 1916 four members of the Chicago Symphony, who had formed a string quartet, appealed to Elizabeth. If she could support them they could quit their “day job” and perform as a quartet full time. When Elizabeth agreed the quartet relocated to Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Within two years the Berkshire Quartet, Elizabeth’s “Berkshire Boys” became the basis of the Berkshire Music Festival at South Mountain eventually known as the Festival at Tanglewood one of the leading summer music festivals in the country.

Mrs. Coolidge started an annual competition for new compositions. The first Berkshire Prize in 1919 was for a viola work. The jury, unable to decide between two works, appealed to Elizabeth to cast her vote. Both composers were dear friends of Mrs. Coolidge. She chose Ernest Bloch’s Suite for Viola and Piano over Rebecca Clarke’s Sonata for Viola and Piano but programed both pieces for the 1916 festival. They have since become staples of the repertory.

Ernest Bloch: Suite for Viola and Piano – IV. Molto vivo (Paul Neubauer, viola; Margo Garrett, piano)

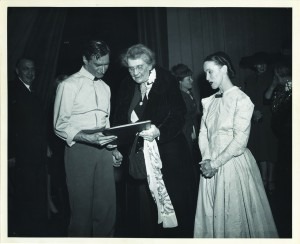

Martha Graham and Erick Hawkins are greeted by Elizabeth Coolidge, center, following the debut performance of “Appalachian Spring.” The Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation Collection, Music Division.

Bloch was a close associate of the newly appointed Chief of the Music Division of the Library of Congress, Carl Engel. Bloch suggested that Coolidge invite the cultured, clever man to the next Berkshire Festival. Once Engel and Coolidge met there was no stopping them. Their friendship soon led to collaboration, first to bring chamber music programs to the Library of Congress in Washington. The fact that there was no performance venue didn’t stop Elizabeth. She advocated building a chamber music hall, “the most perfect and beautiful room for music” and would provide additional funds to support performances and ongoing commissions. The plan required Congressional approval and behind-the-scenes machinations— as there was no mechanism in place to hold and distribute funds at the library. But Elizabeth prevailed and the construction of an auditorium began in 1925.

The first festival took place that year. Composer Charles Martin Loeffler’s setting of St. Francis of Assisi’s Canticle of the Sun was commissioned for the occasion. Mrs. Coolidge, a true visionary, believed manuscripts held in the archives of the Library of Congress ought to be performed, not gathering dust on the shelves. Furthermore, the widest audience should enjoy the music. She had great faith in the power of radio. Elizabeth made certain that radio broadcast equipment was installed in the hall so that performances could be heard across the country.

The trailblazing activities of Mrs. Coolidge and her Foundation included dance. The first ballet commission was Stravinsky’s Apollon Musagète of 1928. Sometimes things did not go smoothly. Stravinsky missed deadlines, as did Ravel, who was late with his Chansons Madécasses. Elizabeth was greatly displeased and tolerated no such nonsense even from the most prominent artists. According to scholar Cyrilla Barr in her presentation The Coolidge Legacy, Elizabeth’s sense of impartiality is reflected in a letter she wrote regarding composer Arnold Schoenberg, who tried to negotiate a higher fee for a string quartet commission than was customary, “… I agree that it would be a great addition to our programs to have his quartet, but I cannot see why we should pay him a large fee…” Fortunately they came to an agreement. Schoenberg’s third and fourth string quartets were completed.

APOLLON MUSAGETE Opéra de Paris (Balanchine)

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge

Although Elizabeth was frugal, nonetheless she was extremely generous to musicians in need. In 1934 when Schoenberg tried to help his student Alban Berg sell the opera score of Wozzeck, Coolidge supplied a large percentage of the funds and during World War II she tried to help artists who were trying to escape war-torn Europe.

Mrs. Coolidge had an instinctive musical sensibility and discerning taste. Under the auspices of the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation she was responsible for an astonishing array of newly commissioned chamber music from American and European composers, which were presented in her lovely auditorium. The pieces are treasured by audiences and musicians alike—Samuel Barber’s Hermit Songs, Op. 29, Ottorino Respighi’s Trittico Botticelliano, Béla Bartók’s String Quartet No. 5, and Francis Poulenc Flute Sonata, in addition to chamber music by composers Ernest Bloch, Bohuslav Martinů, Paul Hindemith, Rebecca Clarke and Frank Bridge. Elizabeth became close friends with virtually every major twentieth century composer and performer of chamber music despite her formidable presence and oftentimes daunting personality.

Samuel Barber: Hermit Songs, Op. 29 – No. 7 Promiscuity (Leontyne Price, soprano; Samuel Barber, piano)

Ottorino Respighi: Trittico botticelliano, P. 151 – I. La Primavera: Allegro vivace (Chamber Orchestra of New York; Salvatore Di Vittorio, cond.)

We owe a debt of gratitude for the 1944 festival, which dedicated an entire program to music created for choreographer Martha Graham, including Copland’s famed Appalachian Spring, scored for thirteen players, and Darius Milhaud’s Jeux de Printemps.

Historic Appalachian Spring with Martha Graham

Martha Graham

Elizabeth continued to perform well into her eighties, practicing several hours a day, taking part in chamber music gatherings. Sadly, she was losing her hearing; According to Ms. Barr, “She once admitted to [her friend] Hans Kindler, ‘You have no idea how difficult it is to concentrate on Brahms when there is an entirely different composition roaring inside one’s head, without rhythm or harmony, but simply incessant noises.’” Mrs. Coolidge dragged her various hearing contraptions to concerts, occasionally a huge ear trumpet contained in an unwieldy black box. Sometimes she turned it off in the middle of a piece. She was not always pleased with the commissions.

Coolidge lived modestly and was able to support the arts in a way that is just as necessary today. Her philanthropy became the model for endowments that followed. Hers was an astounding legacy not only for the magnificent concerts, the Coolidge Auditorium, the Foundation and commissioning of new works, but also for donating her vast collection of original manuscripts and papers. Today the high quality performances continue to date over 100 works including four ballets.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter