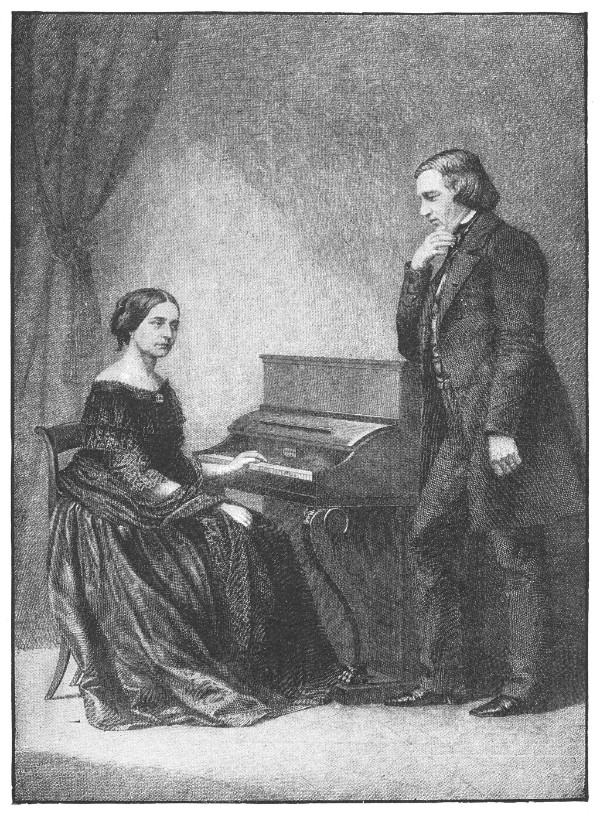

Painting by Walenty Wańkowicz (1799-1842 in Paris) a Polish painter of Belarusian origin.

Born Maria Wołowskis in 1789 in Warsaw, Poland, she astonished her family with her ability to improvise on the spinet—a smaller piano—when she was very young, but women were not accepted into the music schools in those days. Maria began to study the piano at the age of eight with a series of well-respected local teachers who came to their home. She pursued lessons in composition a few years later. Since public concerts were not the fashion nor widespread at the time, Maria’s parents, who were well-connected and enthusiastic patrons of the art, held musical gatherings. Members of the aristocracy, poets, and leading virtuosos of the cosmopolitan city were among the guests and Maria was often featured as the musical entertainment for the evening. These connections would later become important for Maria’s career.

1810 was an auspicious year for Maria. She performed in the major musical centers of Europe, in Warsaw and Paris, Luigi Cherubini heard her perform in one of Paris salons that year and dedicated his Fantasy for Piano to her and she married Polish aristocrat Jozef Szymanowski.

20 Exercices et Préludes

Prelude No. 18 in E Major: Presto

Soon after the marriage Szymanowska bore three children. She retired from performing and turned her focus on composition, writing over 100 works, many of them virtuoso piano pieces such as nocturnes, polonaises and variations. It is not known if Szymanowska studied with the eminent composer John Field—some critics noticed similarities between her compositions and his. Field’s works certainly influenced her, and it was Field who recommended her work to the publisher Breitkopf and Härtel. Szymanowska’s set of 20 Exercises et Préludes met with notable success and they and other works were published in Leipzig, Germany, in 1819. Like Chopin, Szymanowska enjoyed writing études that were both instructive for the pianist and musically attractive to audiences. Her songs and salon pieces were also widely appreciated.

Credit: Wikipedia

Life was difficult. She had to support herself and her children as well as take care of all the tedious aspects of her career—traveling, lodging and procuring engagements, setting ticket prices, managing the box office receipts and determining programs. Szymanowska recruited her brothers and sisters to help manage the business details enabling her to concentrate on the countless hours required to hone her skills.

Caprice sur la Romance de Joconde in E Major

From 1822 to 1827 she toured throughout Russia, Germany, Italy and France. Her programs included contemporary compositions, as well as works for voice and piano. Critics admired her ability to play in a lyrical style, her expression enhanced by melodic ornamentation, and they praised her power, brilliance and precision. Szymanowska became one of the first professional piano virtuosos of the time and possibly one of the first to perform music from memory, well before Franz Liszt and Clara Schumann. In fact, she caused quite a stir during a concert in Poland in 1823 when she performed her Caprice sur la Romance de Joconde. It was not even written out.

Szymanowska’s concerts were particularly well received in Russia where she rubbed shoulders with the aristocracy. Tsar Alexander officially appointed Szymanowska, to the coveted position First Pianist to the Empresses Maria Fedorovna and Elizaveta Alekseevna, at the Russian court in 1823, which provided financial security and enhanced her reputation.

Russian gentry hoped to emulate their European counterparts, and were eager to adopt the trappings of western society. Learning to play the piano, especially if they could study with the distinguished court performer, offered a certain caché. Szymanowska decided to settle in St Petersburg in 1827. The annual court stipend and guaranteed pension, her piano teaching, and music publications, which produced royalties, and her performances both public and private, offered Szymanowska and her family a comfortable living. She was one of very few women artists of the time who thrived.

It is said that when she made a triumphant return to perform in Warsaw in 1827 at the National Theater, Chopin was in attendance. Once he began to establish his career Szymanowska was a staunch supporter. There are some striking commonalities between Chopin’s études and Szymanowska’s, particularly her Etude No. 18 in E major.

Like her parents before her, Szymanowska established salon evenings. Poets, musicians, and the most stimulating minds of Europe attended. Over the course of her career she developed friendships with writers including Pushkin, Mickiewicz and Goethe (who dedicated his well-known poem Aussöhnung to her); and composers Cherubini, Beethoven, and Glinka. Instead of keeping a diary, Szymanowska kept a scrapbook. She collected memorabilia from these famous artists who left their marks in poetry, drawings, melodies and signatures—a testament to her extensive influence.

Tragically, in 1831, a cholera epidemic in St. Petersburg claimed her life, cutting her astounding career short. Szymanowska though, is no longer forgotten. There has been a resurgence of interest in her legacy. In 2011, the first International Maria Szymanowska Conference took place in Paris. CD’s of her songs and her complete piano and chamber music have been released and scholarly articles as well as books have been written about her artistry by authors Slawomir Dobrzanski and Anna Kijas. For more information see the charming blog : Chopin with Cherries. Maria Szymanowska was an inspiration to the generations of women artists who followed in her footsteps.

Maria Szymanowska Nocturne