Claude Debussy

Credit: http://az616578.vo.msecnd.net/

It wasn’t the first time that Yao had his finger in art: two years earlier, Yao had attacked classical music.

In 1962, China’s cultural circles decided to publish various biographies, musical scores and corpus of Debussy to commemorate the iconoclastic composer’s 100th birthday. As part of the celebration, a translation of Monsieur Croche, a collection of Debussy’s critical essays on music, appeared in 1963. In that low-information time, the publishers could only get the 1926 French version, in which only 25 articles were included. The translation job fell to Zhang Yuhe, a young French teacher from Shanghai College of Foreign Languages and a newcomer to translating music literature. Debussy had his own unique way of using language. Unfortunately, it was difficult for Zhang Yuhe to comprehend Debussy’s essays properly because he wasn’t a professional musician. For another thing, it was tough to translate Debussy’s wit and wisdom accurately from French to Chinese. But the book sold well. The publisher planned to reprint it and asked the author for revision if needed.

Before Zhang Yuhe could spare the time to do so, Yao Wenyuan published a vitriolic article titled Please Take a Look at “An Innovative and Distinctive View” in Wenhui Daily. The ill-founded critique used the mouthpiece of Shanghai government to attack Zhang’s Debussy translation. Yao took for granted that bourgeois musicians were all corrupt and reactionary. On these grounds, Yao deemed Debussy arrogant and contemptuous and someone who would never solicit views from the proletariat.

A day after the publication of Yao Wenyuan’s critique, the editor of Wenhui Daily received a phone call, on which a man with a strong Hunan accent criticized Yao’s critique as smattering and requested a confrontation with the author. Soon afterward the man published a set of editorials under the pen name Shangu to rebuke Yao and vigorously defend Debussy. The man was He Luting, director of the Shanghai Conservatory of Music since 1949.

In that special atmosphere, everyone was cautious about expressing opinions. Only a few unyielding intellectuals sided with He Luting. Still, the debate, which went beyond the realm of scholars, triggered a firestorm of controversy in China’s musical circle. The authorities even organized a counter campaign against He Luting.

Monsieur Croche

Credit: http://www.le-livre.fr/

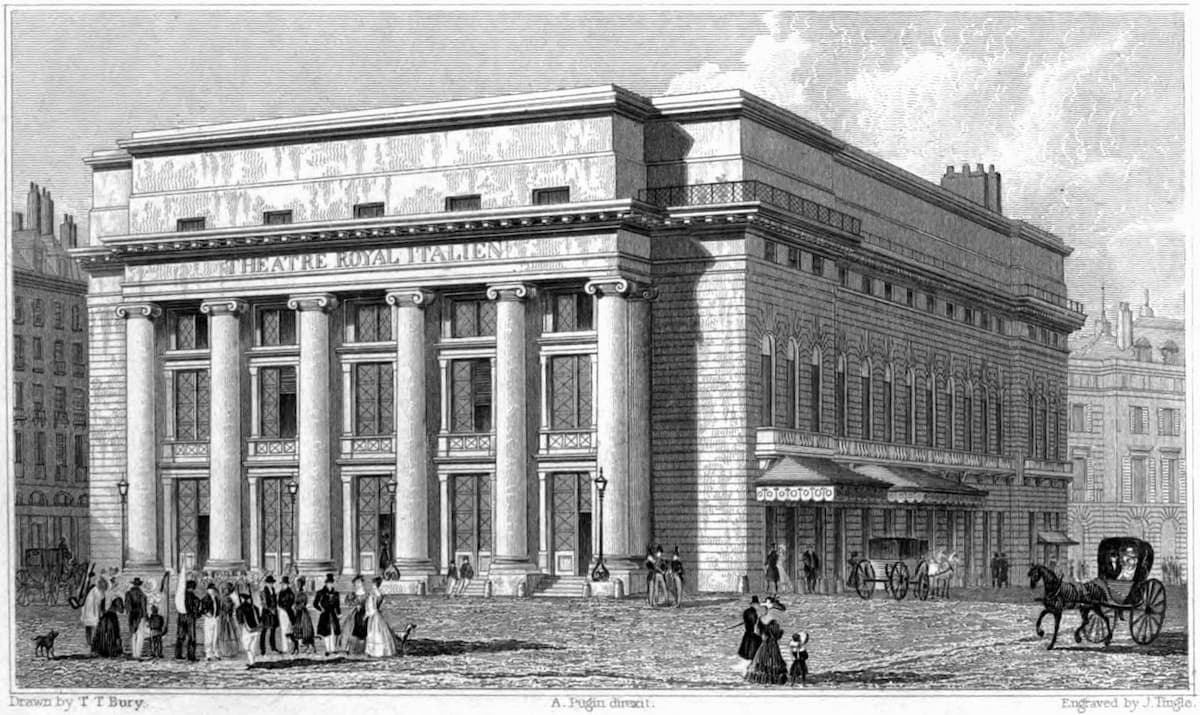

Here comes the question: why did Yao vilify Debussy? The answer is bureaucracy. Ke Qingshi, the party’s secretary of Shanghai at the time, met with Mao and received his directive. Mao said that the translators’ preface commentaries to some western works lacked “class viewpoint.” Ke passed those words onto his colleague and friend Zhang Chunqiao, who would become a member of the Maoist radical group later dubbed “the Gang of Four.” Zhang then passed Mao’s directive to Yao, because they were both in charge of propaganda. He urged Yao to find some targets. Yao was afraid to ask Mao which commentaries he had meant and Mao did not elaborate. Eventually Yao came upon the translation of Monsieur Croche, whose preface referred to the original author’s profound, original and challenging insights. Debussy always insisted on his artistic viewpoints and never followed the crowd. He criticized the bureaucracy of the Opéra national de Paris, laughed at the audiences who wore gorgeous clothes but knew virtually nothing about music, and even created a fictional character “Monsieur Croche” to express his disagreements. Therefore, Yao defined it as “lacking class viewpoint” and decided to launch an attack.

The story doesn’t end there. At the time, Zhang was too young to understand the darkness of politics. He contended against the specific prejudice against Debussy and was blacklisted. Zhang Yuhe immigrated to Canada after the political disturbance. Encouraged by his intimates, in 2012 Zhang published a new version of the translation of Monsieur Croche in mainland China which had more chapters to commemorate the great composer’s 150th birthday.

Ciccolini plays Reverie