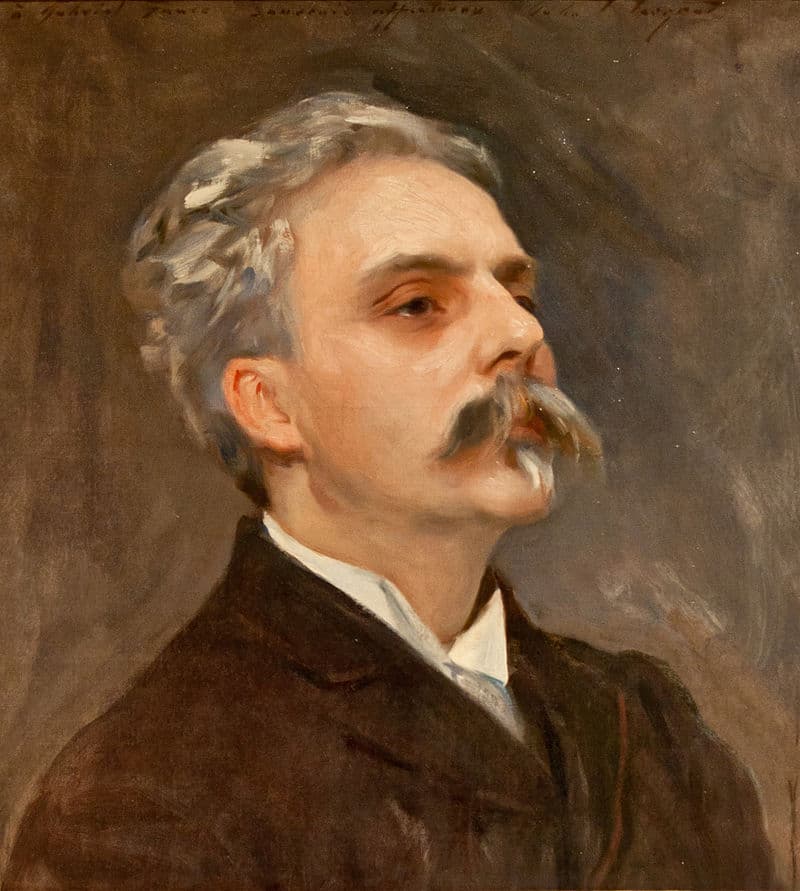

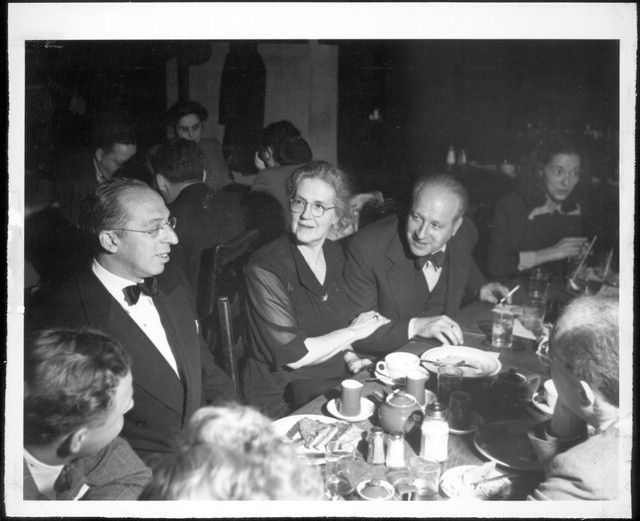

During his studies with Nadia Boulanger in Paris, American composer Aaron Copland (1900-1990) met France’s most important composers, including Saint-Saëns and Fauré.

Aaron Copland and Nadia Boulanger

Once he had returned to America, Copland became an outspoken champion and advocate of Fauré’s music. He writes, “The position of Gabriel Fauré in the contemporary musical movement is, in several respects, curious and unique. Perhaps no other composer has ever been so generally ignored outside his own country while at the same time enjoying an unquestionably eminent reputation at home… In America, and one might add, in all other countries except France, his work is practically unknown… He composed his first songs in 1865 and has continued for almost sixty years to produce compositions, which, paradoxically, become ever more spiritually youthful and serene as he becomes physically older and weaker.” According to Copland, Fauré foreshadowed the atonal music of Schoenberg, and in his Hommage à Fauré dating from 1923 Copland includes a string quartet version of Fauré’s Prelude, Op. 103 No. 9.

Aaron Copland: Hommage à Fauré, “Prelude” (arr. for String Orchestra) (Musica Vitae Chamber Orchestra; Péter Csaba, cond.)

Elisabeth de Caraman-Chimay

Born Elisabeth de Caraman-Chimay in 1860, she was the daughter of a Belgian Prince and great-granddaughter of the founder of the Brussels Conservatoire. Her mother was Marie de Montesquiou, who studied piano with Chopin’s last student and Clara Schumann. She married the fabulously wealthy banker Count Henry Greffulhe, and to escape a boring, abusive and restrictive marriage, she established her own music salon. In no time, she was considered the “queen of the salons of the Faubourg Saint-Germain in Paris.” Gabriel Fauré first met her in 1887 and quickly started to organize concerts for her salon. In turn, the Countess invited him to stay at her summer villa on the cliff-top overlooking Dieppe. Somewhat tellingly, Fauré referred to her as his “King of Bavaria.” Initially, Fauré’s “Pavane,” one of his most popular works, was scored for piano and chorus. But when he decided to dedicate the work to the Comtesse Greffulhe, he was looking to make it a somewhat grander affair. The Comtesse recommended the addition of an invisible chorus, dancers and a text originating with her cousin Robert de Montesquiou. Fauré wrote,”M. de Montesquiou … has most kindly accepted the egregiously thankless and difficult task of setting to this music, which is already complete, words that will make our Pavane fit to be both danced and sung. He gave it a delightful text: sly coquetries by the female dancers and great sighs by the male dancers, which will singularly enhance the music. If the whole marvelous thing with a lovely dance in fine costumes and an invisible chorus and orchestra could be performed, what a treat it would be!” And so it came to pass on the island in the Bois de Boulogne on 21 July 1891.

Gabriel Fauré: Pavane, Op. 50

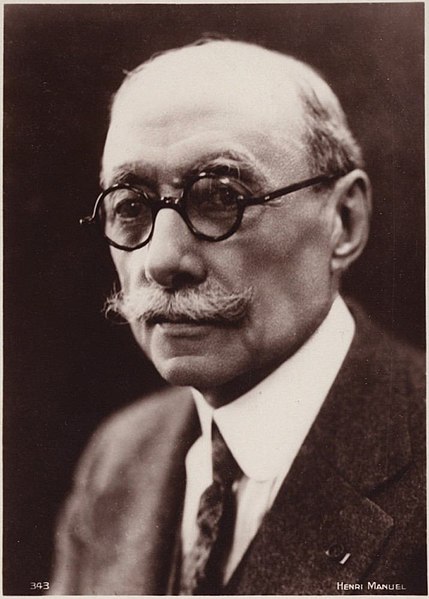

André Messager

André Messager (1853-1929) is primarily remembered as a composer of light music. Initially, he had limited exposure to music, “you would not find any musicians among my ancestors,” he writes. “When very young, I learned the piano, but later on, my intentions to become a composer met with such opposition from my father.” Eventually, he was sent to study at the École Niedermeyer in Paris, where he took lessons in composition with Gabriel Fauré. Fauré immediately acknowledged his comprehensive ability stating, “he is familiar with everything, knowing it all, fascinated by anything new.” They quickly moved from being master and student to being firm friends and occasional musical collaborators. In 1874, Messager succeeded Fauré as organiste du chœur at Saint-Sulpice, Paris, working under the principal organist, Charles-Marie Widor. Messager and Fauré frequently traveled together, and in 1879 they visited Cologne to see Wagner’s “Rheingold” and “Walküre.” They saw the complete Ring cycle in Munich, and in 1888 made their first pilgrimage to Bayreuth, which inspired an entire generation of French musicians. On that occasion, they created an entertaining piece for piano four-hands called “Souvenirs de Bayreuth.” Apparently, they performed this little gem with great regularity in the leading music salons of Paris.

Gabriel Fauré/ André Messager: Souvenir de Bayreuth (Patrick de Hooghe, piano; Pierre-Alain Volondat, piano)

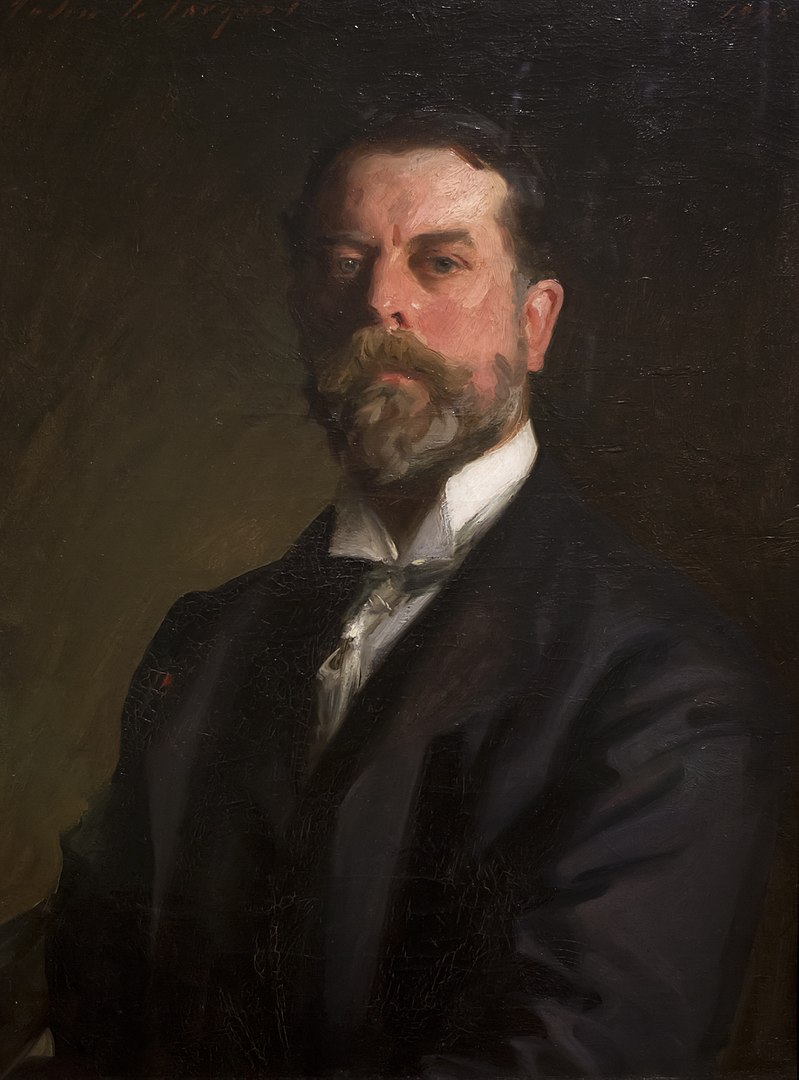

John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) was one of the leading portrait painters of his generation. Born in Florence to American parents, he lived in Europe for most of his life. He spoke excellent French, which gained him entrée to the highest artistic circles of Paris. “He had a masterly technique and great psychological insight as a painter, and he was also an accomplished pianist who accompanied amateurs and professionals.” Sargent was described as a consummate musician, with the ability to play difficult music at sight, and when cornered by a difficult piece he couldn’t play, “revealed his genuine talents for music by playing all that which was and is more essential.” Fauré met Sargent in Paris, and they became lifelong friends. In fact, Fauré ranked high in Sargent’s pantheon of great composers; perhaps second only to Richard Wagner. It goes without saying that Fauré posed for Sargent, who produced a total of 4 portraits. And since Fauré’s music was not universally appreciated, Sargent took it upon himself to organize studio concerts of his music in London.

Gabriel Fauré: Shylock, Op. 57 (Nicolai Gedda, tenor; Orchestre national du Capitole de Toulouse; Michel Plasson, cond.)

Fauré and the Hasselmans

Marguerite Hasselmans (1876-1947) was the daughter of the famed French harpist and composer Alphonse Hasselmans. He was a renowned virtuoso and became professor of the harp at the Paris Conservatoire in 1884. His daughter Marguerite trained as a pianist, and she conversed in Russian and loved talking philosophy. She certainly was a highly confident woman, “smoking in public and wearing makeup.” By 1898, Marguerite was married to André Tracol, a violinist in the orchestra of the Paris Conservatory. Fauré first cast his eyes on her in 1900; he was 55 and about the same age as her father. Marguerite became Gabriel’s mistress, and he furnished her a luxurious apartment on Rue de Wagram, where she established a piano studio. Marguerite was his constant companion, and at a concert with the Societé des Concerts, she performed the Mozart C-minor piano concerto with a cadenza Fauré especially composed for her. Surprisingly, Fauré never dedicated a composition to her, but she did perform the world premiere of his Fantaisie Op. 111 in 1919.

Gabriel Fauré: Fantaisie, Op. 111 (Stéphane Lemelin, piano; CBC Vancouver Orchestra; Mario Bernardi, cond.)

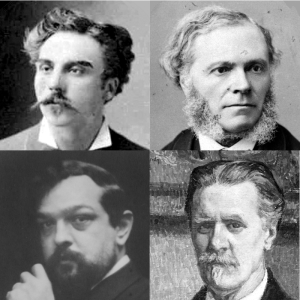

Members of the Société nationale de musique: Fauré, Franck, D’Indy and Debussy

Founded during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71, the “Société nationale de musique” sought to exclusively promote French music of rising contemporary composers. As the constitution stated, “The proposed purpose of the Society is to aid the production and popularization of all serious works, whether published or not, by French composers. To encourage and bring to light, as far as lies within its power, all musical attempts, whatever their form, on condition that they give evidence of lofty artistic aspirations on the part of their author. Fraternally, with entire forgetfulness of self, with the firm resolve to aid each other with all their capacity, the members will unite their efforts, each in his own sphere of action, to the study and performance of the works which they shall be called upon to select and interpret.” Founding members of the society, among others, included Théodore Dubois, Henri Duparc, César Franck and Gabriel Fauré. The society essentially shunned opera, and concentrated on chamber music. Fauré subsequently recalled, “The truth is that before 1870, I would never have dreamt of composing a sonata or a quartet. At that period there was no chance of the composer getting a hearing with works like that.” Among the works premiered by the society are Fauré’s First and Second Piano Quartets and the song cycle “La Bonne chanson.”

Gabriel Fauré: La bonne Chanson, Op. 61 (Stéphane Degout, baritone; Alain Planès, piano)

Mrs. Patrick Campbell

She was born Beatrice Rose Stella Tanner (1865-1940), but eventually changed her name to Mrs. Patrick Campbell. “Mrs. Pat,” as she was informally known, was an English stage actress who appeared in plays by Shakespeare and Shaw, and she even briefly featured in Hollywood films. When Maurice Maeterlinck’s play Pelléas et Mélisande was first staged in English, Mrs. Pat invited Debussy to compose incidental music. However, Debussy was busy with turning the play into an opera and curtly declined. Gabriel Fauré was in London in March and April 1898, and he was introduced to Mrs. Pat. Still reeling from Debussy’s rejection, she now invited Fauré to compose the music for the production. Fauré wrote to his wife, “I will have to grind away hard for Mélisande when I get back. I hardly have a month and a half to write all that music. True, some of it is already in my thick head!” The composer combined music for incomplete or unsuccessful works and crafted 19 pieces of varying length and importance. Fauré conducted the premiere at the Prince of Wales’ Theatre on 21 June 1898, and Mrs. Pat was over the moon. She wrote, “he had grasped with most tender inspiration the poetic purity that pervades and envelops M. Maeterlinck’s lovely play.” Fauré subsequently compiled a four-movement suite from the original theatre music, and the work is primarily remembered in that particular form.

Gabriel Fauré: Pelléas et Mélisande, Op. 80 (Suite) (Academy of St. Martin in the Fields Orchestra; Neville Marriner, cond.)

Charles Van Lerberghe

Scholars have suggested, “Gabriel Fauré’s mélodies offer an inexhaustible variety of style and expression that have made them the foundation of the French art song repertoire. During the second half of his long career, Fauré composed all but a handful of his songs within six carefully integrated cycles.” In 1906, the Belgian poet Albert Mockel introduced Gabriel Fauré to Charles Van Lerberghe’s book of ninety-six poems entitled “La Chanson d’Ève.” The poet was strongly identified with the symbolist movement, with growing atheism and his anticlerical stance readily identifiable in the later works. Those sentiments, challenging established norms at the start of the 20th century, made his work highly popular. We do know that Fauré’s religious views evolved over time, and at the time he began setting “La Chanson d’Ève”, he was no longer working for any religious institutions. According to a friend, “Fauré’s—and I have it from his lips—the word ‘God’ was merely an immense synonym for the word ‘Love.’ This belief… by its sheer breadth… sooner or later must have worn down the protests of slack epicurean indifference and irreligiosity which various musical camps heaped upon him, really out of partisanship, though some would claim that such an attitude of philosophical neutrality was unbefitting a former organist of La Madeleine.” Fauré’s musical setting of Van Lerberghe takes its bearing from the composer’s candid reflection on the subject of God. As he writes to his wife in 1922, “In one of your recent letters, you spoke to me of your admiration for the created world and your disdain for its creatures. Is that fair? The universe is order, man is disorder. But is that his fault? He was thrown onto this earth, where everything seems harmonious to us and where he goes lurching, stumbling from his first day to his last; he was thrown here weighted down with a burden of physical and moral ailments to the point that original sin had to be invented to explain this phenomenon!”

Gabriel Fauré: La chanson d’Eve, Op. 95 (Veronique Dietschy, soprano; Philippe Cassard, piano)

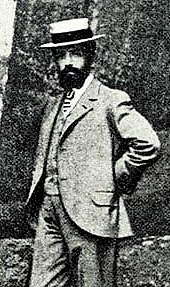

Ovide Musin, 1880

The Belgian violinist and composer Ovide Musin (1854-1929) is one of the most important representatives of the Franco-Belgian violin school in the 19th and 20th centuries. Forced to leave his homeland during the Franco-Prussian War, Musin came to Paris in 1872 and studied with Hubert Léonard. Léonard introduced Musin to the Parisian salons, and he quickly made the acquaintance of César Franck, Camille Saint-Saëns, and Gabriel Fauré. In fact, Camille Saint-Saëns dedicated the “Morceau de concert pour violon,” Op. 62 to Musin, and Fauré intended to compose a violin concerto for him. He worked on it between 1878 and 1879, and the first and second movements premiered with Musin as the soloist. The “inventive second movement, full of charm and passion”, enchanted a contemporary reviewer. However, the opening “Allegro” was described as “dull and monotonous.” Fauré never completed the concerto, and curiously, only the first movement has survived. The enchanted second movement appears to have been destroyed by Fauré himself, as he wrote to his wife, “When I get back to Paris, I shall spend a little time each day giving you all my sketches and drafts and everything else of which I want nothing to survive after me so that you can burn them.”

Gabriel Fauré: Violin Concerto, Op. 14 (Rodolfo Bonucci, violin; Mexico City Philharmonic Orchestra; Enrique Bátiz, cond.)

Pierre Lalo, 1902

Pierre Lalo (1866-1943) was the son of composer Edouard Lalo, and he made his name as a music critic and translator. From 1896, he contributed his first articles, and a couple of years later, he was appointed music critic of the “Revue de Paris” and “Le Temps.” His reviews are described as “conservative, witty, astute and sporting linguistic finesse, which occasionally turned to virulence.” A persistent trope in his writings was his dislike for the music of Ravel. Nevertheless, Lalo served on the governing boards of the Paris Conservatoire, and he became a close friend and trusted adviser of Ravel’s teacher, Gabriel Fauré. Lalo was less hostile to the music of Debussy, and his article “Maurice Ravel et le Debussysme” in 1907 stirred up a heated debate amongst the public. In honor of the passing of his wife Noémi Lalo in 1913, Fauré dedicated his F-sharp minor Nocturne, Op. 104/1 to her. “The funeral effect of tolling bells,” a critic wrote, “may also reflect the composer’s own state of anguish, with deafness encroaching.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Gabriel Fauré: Nocturne No. 11 in F-sharp minor, Op. 104/1 (Pascal Rogé, piano)