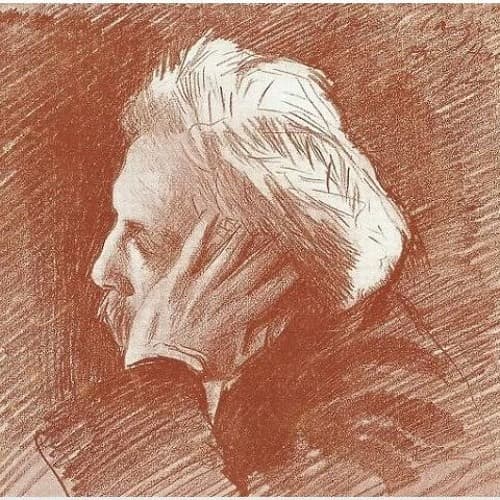

An example of a fugue structure © composerfocus.com

Among the most feared course requirements for many aspiring composers and students of music is a class simply labeled “Fugue.” And it’s no wonder, as a good many universities that still teach this kind of skills will ask you to sit in this particular class for an entire semester. And invariably, you will have to compose a fugue for your final project. The basic premise is simple enough. Take a short melody or phrase introduced in one part. That melody then taken up by other parts and developed by interweaving the parts. What sounds simple is in reality a highly complex process of rules and restrictions that is commonly regarded as the most fully developed procedure of imitative counterpoint.

Bach’s unfinished fugue in The Art of Fugue

It is hardly surprising that a good many composers past and present consider the process of writing a fugue an “exercises in a dead language.” Yet for the musical and expressive genius Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), the possibilities within these restrictions were endless. His most celebrated and extensively studied collection of contrapuntal movements The Art of Fugue explores the possibilities inherent in a single musical theme. Demonstrating every compositional technique and method known to him, Bach composed eigthteen movements; fourteen fugues and four canons. The collection remained unfinished, however, as Bach died while incorporating his musical signature. How many more gripping jewels he might have composed, we will never know.

J.S. Bach: The Art of Fugue, BWV 1080 (arr. for string quartet) (Emerson String Quartet)

Mozart’s “Jupiter” fugal entries

Even during Bach’s lifetime, fugues and other forms of imitative counterpoint were considered seriously old fashioned. The aesthetics of music and culture had simply changed dramatically. During his extensive travels, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) was exposed to a multiplicity of compositional styles, tastes and genres. Mozart, the undisputed pop star of the 18th century, unrelentingly integrated, synthesized and transformed stylistic and musical conventions. It might reasonably be argued, however, that it took the encounter with the music of Bach and all those marvelous fugues that eventually produced compositions of universal appeal and stunning individuality. Mozart had been exposed to counterpoint throughout his life, but he engaged in serious study of fugue only during the 1780s. The diplomat Baron Gottfried van Swieten—who penned the libretto for Haydn’s Creation—was an avid collector of musical manuscripts. Wanting to have these works performed, he held regular musical parties in his Viennese residence, and Mozart was a steady guest. He reports to his sister, “nothing is played but fugues by Handel and Bach.” Mozart’s contact with the mastery of the German contrapuntal tradition opened a completely new musical horizon. He produced a number of stand-alone fugues, and this newly gained compositional skill helped to inform the creation of his final sublime orchestral masterpieces. Words simply can’t describe the jaw-dropping and breathtaking fugal display of quintuple invertible counterpoint in the final movement of the “Jupiter.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Symphony No. 41, “IV Molto allegro” (Philharmonia Orchestra; Otto Klemperer, cond.)

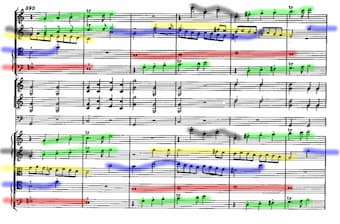

Johannes Brahms

In 1899, Ernest Walker addressed the 25th session of the Royal Musical Association with a lecture on Johannes Brahms. He described the composer’s musical style as a “fusion of heterogeneous materials with the desire for emotional expression.” Essentially then, Walker saw Brahms as the logical union of Bach’s contrapuntal art and Beethoven’s formal perfection. To his contemporaries and critics, Brahms looked like a bastion of musical conservatism. Surprisingly, it was Arnold Schoenberg who suggested that Brahms was “a great innovator in the realm of musical language, and that his chamber music prepared the way for the radical changes in musical conception at the turn of the 20th century.” But let’s be clear, musical language for Brahms always starts in strict accordance with his extensive knowledge of counterpoint and fugue. He studied every available treatise on this subject and the integrity of the musical structure is paired with the attempt to achieve a deeper level of contrapuntally inspired motivic cohesion. Just listen to the finale of his E-minor Cello Sonata, a movement that epitomizes Brahms’ style. The fugal subject is derived from Bach’s Art of Fugue, and the movement weaves together a highly contrapuntal style with the exploitation of the possibilities inherent in sonata form. Through his study of fugue, Brahms became aware of his place within the Classical tradition, and the inspiration he drew from it resulted in the revitalization of classical form.

Johannes Brahms: Cello Sonata No. 1, Op. 38 “Allegro” (Yo-Yo Ma, cello; Emanuel Ax, piano)

Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin

As a young student, Nadia Boulanger discovered Maurice Ravel cheerfully writing counterpoint exercises in Fauré’s class. She recalled, “I had a surprise when I found myself in Fauré’s class and discovered Ravel was there, too, doing as I used to do then, traditional counterpoint. I didn’t always find it interesting, yet it seemed quite natural that Ravel should do it… It was only years later that I asked him why he was still studying counterpoint. ‘One must clean the house from time to time; I often do it that way,’ he replied.” Ravel’s devotion to the discipline of counterpoint and fugue provided the basis for his elegant and imaginative contrapuntal virtuosity. In fact, Ravel’s first-level entries in the Prix de Rome competitions between the years 1900 and 1905 were naturally five fugues. His engagement with strict contrapuntal forms continued in the piano suite Le Tombeau de Couperin, completed when he was discharged from military service in 1917. First performed by Marguerite Long in 1919, the audience was suitably surprised and impressed to discover that a meandering and jazz-inspired “Fugue” was part of the collection.

Maurice Ravel: Le tombeau de Couperin, No. 2 “Fugue” (Rinko Hama, piano)

The Esterházy castle

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) entered into the services of the Esterházy family as a court musician in 1761, and he would remain on the job for a total of 41 years. Much of his career was spent at the family’s remote estate, with Haydn reporting “Well, here I sit in my wilderness; forsaken, like some poor orphan, almost without human society… nobody is nearby who could distract me or confuse me about myself. I had no choice but had to become original.” Haydn had turned forty and was working on his six string quartets opus 20, when originality struck. Whereas in earlier efforts he would often fuse the viola and cello parts together in one musical line, he now made the fullest use of four completely independent voices. And one of the clearest ways of demonstrating complete independence of individual voices is to write strict counterpoint and fugues.

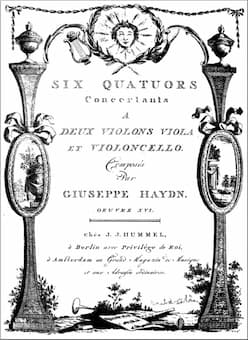

Haydn: Sun Quartets, Op. 20

For his opus 20, subsequently nicknamed “Sun Quartets” because the sun is displayed on the cover of the first edition, Haydn composed three fugal finales. Haydn was undoubtedly the leader of fugal composition and technique in the Classical era, and writing fugal finales also offered a brand new solution to the relative weighting of all movements. These fugues are not dry academic exercises, however, as Haydn greatly expanded the texture and dynamics and experimented with flexible phrase length and structure. Every measure is full of variety and unpredictability, with Haydn combining his extensive knowledge of historical sources with the furthest reaches of his brilliant musical imagination.

Joseph Haydn: String Quartet No. 24, Op. 20, No. 6 “Fuga con tre soggetti” (Kodály Quartet)

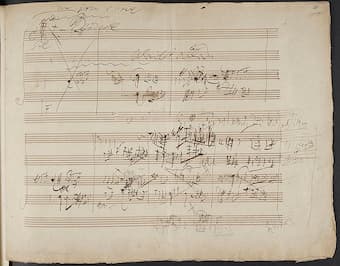

Beethoven: Sketches for the String Quartet Op. 131

As a young and eager student of music, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) received thorough instruction in counterpoint and fugal writing. During his early days in Vienna he even attracted attention by playing fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier on his recitals. Fugal passages are found in his early piano sonatas and also in the “Eroica,” but fugues did not take on a central role in Beethoven’s oeuvre until late in his career. No doubt you are familiar with the fugue in the Cello Sonata, Op. 102 No. 2, the technically devilish fugue in the “Hammerklavier,” the massive dissonant fugue published as “Große Fuge” Op. 133, and fugal passages in the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth Symphony. However, it is his Opus 131 string quartet that is considered the pinnacle of his creative output. Writing in 1870, Richard Wagner published a poetic description of the work, “Tis the dance of the whole world itself: wild joy, the wail of pain, love’s transport, utmost bliss, grief, frenzy, riot, suffering, the lightning flickers, thunders growl: and above it the stupendous fiddler who bears and bounds it all, who leads it haughtily from whirlwind into whirlwind, to the brink of the abyss – he smiles at himself, for to him this sorcery was the merest play—and night beckons him. His day is done.” Written during a period of immense personal suffering, the opening fugue has been called “the most superhuman piece of music that Beethoven has ever written.” It is like a mysterious vision of another universe and represents for some critics “the melancholiest sentiment ever expressed in music.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 14, Op. 131 “Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressive” (Kodály Quartet)

Simon Sechter

A few months before his death, Franz Schubert (1797-1828) first laid eyes on a score of Handel oratorios. “Now for the first time,” he writes, “I see what I lack, but I will study hard with Sechter so that I can make good the omission.” Simon Sechter was probably Vienna’s most famous teacher of counterpoint, and he recalled, “A short time before Schubert’s last illness he came to me… in order to study counterpoint and fugue, because, as he put it, he realized that he needed coaching in these.”

Organ at Heiligenkreuz Monastary

Schubert only managed to have one lesson with Sechter, before he was taken severely ill. He wrote to a friend eight days later, “I am ill. I have had nothing to eat or drink for eleven days now, and can only wander feebly and uncertainly between armchair and bed.” One week later Schubert passed away. Around his lesson with Sechter and his untimely death, Schubert and his friend, the composer Franz Lachner, visited the Heiligenkreuz monastery south of Vienna. Apparently, it was Schubert who suggested that they each write a fugue for the famous organ, which they both did. The Schubert manuscript is lost, but a copy of the work, written in four staves instead of the normally three for organ, did survive. As such, it was first published in 1844 for organ or piano four-hand, but it might well be the case that this fugue represents the very last composition Schubert ever completed.

Franz Schubert: Fugue in E minor, D. 952 (Tal and Groethuysen Duo)

Dmitri Shostakovich © Deutsche Fotothek

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) rapidly composed his Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues between 10 October 1950 and 25 February 1951. This polyphonic cycle is the first work composed in the twentieth century that follows the tradition and the dimension of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. The Shostakovich cycle embraces all twenty-four keys, however, it is organized around the circle of fifths, and not in chromatic ascending order like Bach. We know that Shostakovich played the Bach preludes and fugues as a young boy, and in 1950 he was an honorary member of the jury of a piano competition organized in Leipzig for the 200th anniversary of the death of Bach. Bach’s music, and especially the Well-Tempered Clavier, must have given Shostakovich a certain creative impulse and in conversation with some German musicians in Leipzig he exclaimed, “Why shouldn‘t we try to continue this wonderful tradition.” Back home, Shostakovich was in political hot water, fired from his teaching positions in Moscow and Leningrad, with his music officially banned from concerts and broadcast. In fact, he was on the verge of suicide, and he “decided to start working again… I am going to write a prelude and fugue every day. I shall take into consideration the experience of Johann Sebastian Bach.” As with Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert, the fugue served as the vehicle for the expression of the most personal, intimate and uncompromising thoughts and feelings.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Dmitry Shostakovich: 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87 (Excerpts) (Olli Mustonen, piano)