After the quadrille had had its day, the waltz took the dance floors of Europe by storm. The title for the dance comes from the German meaning to revolve and that twirling motion was the primary characteristic of the form. Of all the dances we’ve been discussing, however, it’s probably the waltz that you know already: you know the position to hold your partner and, if you might be a bit vague on the steps, you know that it’s in triple time: one- two-three, one-two-three…

The waltz started as a peasant dance, first described in the late 16th century, in some horror, as a dance where the dancers held each other so closely that their faces touched. That close position was one of the dance’s controversies. In Vienna of the 18th century, the waltz ascended from being a dance of the servants or peasants to being a dance of the higher classes. It reached England in 1791 but wasn’t really popularized until the early 19th century.

Where the minuet was known for its stateliness, the waltz was considered simpler and less sophisticated and was one of the factors contributing to its popularity. By the late 18th century, the Berlin fashion magazines were reporting that, in Berlin, ‘waltzes and nothing but waltzes are now so much in fashion that at dances nothing else is looked at; one need only be able to waltz, and all is well’.

Those who objected to the waltz took exception to two factors: its speed, based on medical grounds, that the dance was bad for the health considering the speed of the dancers as they whirled around the room. They also objected on moral grounds because of the closeness in the dancers’ hold on each other. One dancing master, writing in 1816, defended the waltz, saying that it was a promoter of vigorous ‘health and productivity of a hilarity of spirits’.

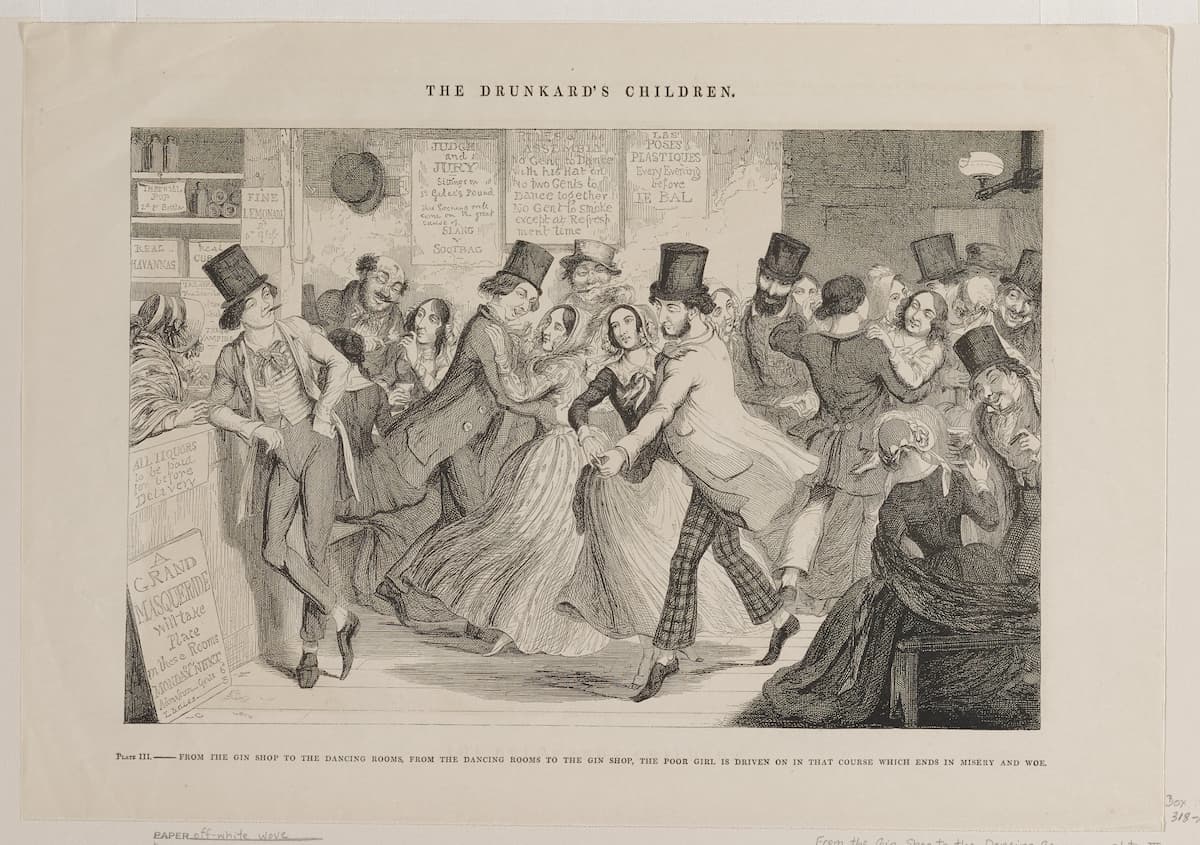

As part of his series of engravings about the dangers of alcoholism, British caricaturist George Cruikshank depicted the danger of close dances like the waltz, such as in this picture from The Drunkard’s Children:

Cruikshank: The Drunkard’s Children, illustration 3: From the Gin Shop to the Dancing Rooms, from the Dancing Rooms to the Gin Shop,

the Poor Girl is Driven on in That Course Which Ends in Misery, 1848 (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Although Mozart never wrote a waltz, he did write music that was in triple time, but which were given more traditional titles such as ländler or Deutscher – often when these were published in other countries, they were renamed waltzes by their local publishers. Beethoven wrote his Diabelli Variations upon being sent a Waltz by Diabelli.

Ludwig van Beethoven: 33 Variations on a Waltz by Diabelli in C Major, Op. 120, “Diabelli Variations” – Thema: Vivace (Konstantin Scherbakov, piano)

It’s not until Schubert that we have a composer who really writes waltzes. In his collection 36 Originaltänze (36 Original Dances), D.365 (Op.9), which is also known as his ‘First Waltzes’,

Franz Schubert: 36 Originaltanze, Op. 9, D. 365, “Erste Walzer” (Michael Endres, piano)

This was perfect music for the home: simple waltzes for the piano that could be played while your sisters and brothers danced and practiced before going out to display them in public.

Then it was Weber, however, who took the waltz out of the living room and onto the concert stage, with his work for piano solo Aufforderung zum Tanz. This was published in 1819 and quickly moved from the piano to the orchestra in the hands of Hector Berlioz.

George GoodwinKilburne: The Recital

Carl Maria von Weber: Aufforderung zum Tanze (Invitation to the Dance), Op. 65, J. 260 (orch. Berlioz) (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Herbert von Karajan, cond.)

When the great Viennese composers Joseph Lanner and Johann Strauss I took on the dance around 1830, its popularity could no longer be ignored. Lanner and Strauss made changes to the old 8-measure melodies by increasing them to sixteen measures in length and speeding up the tempo. Following the example created by Weber, introduction and codas were added to the body. What became increasingly more important, as well, was the naming of the waltz. Sometimes they were named for places, such as Lanner’s Die Schönbrunner (The Schönbrunn Waltz), named for the palace in Vienna, Johann Strauss I’s Wiener-Carnevals-Walzer (Vienna Carnival Waltz), or Johann Strauss II’s immortal ode to the Danube: An der schönen, blauen Donau (The Beautiful Blue Danube).

Joseph Lanner: Mitternachts Waltz (Midnight Waltz), Op. 8 (Orchestre Régional de Cannes; Wolfgang Dörner, cond.)

Lanner has his followers who loved his delicacy and melodies and Strauss I was loved for his rhythmic variety. Strauss took his orchestra on tour, increasing the international popularity of the dance. Josef Gungl from Berlin was the first to take his waltz orchestra to the US, in 1849, but it was still the Strauss family that ruled the dance floor until about 1870, when Johann Strauss II moved over to operetta.

Julius LeBlanc Stewart: The Ball, 1875

With the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian ruling class in WWI, the waltz declined rapidly, being replaced by popular music from the US, and with Berlin replacing Vienna as the center for light music. In Ravel’s La valse, we have the old dance whirling itself to death. Commissioned by Serge Diaghilev, but rejected by him, it was finally staged by Ida Rubinstein, with choreography by Bronia Nijinska. Vaslav Nijinsky’s sister.

The waltz that we know now isn’t usually the whirling brilliance of the Viennese waltz, but rather the slow waltz that came out of Boston to invade Europe in its turn.

Frederick Vezin: At the Ball, 1925

The waltz hasn’t died, it’s just not the ruling dance form it was a century ago. It still shows up in musicals, such as The Carousel Waltz by Richard Rodgers in 1945. The great docking scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and the film made of the final public performance by The Band in 1976 was entitled The Last Waltz, signifying their farewell concert appearance.

A country dance becomes a home dance becomes a controversial public dance until it dances out of our lives.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter