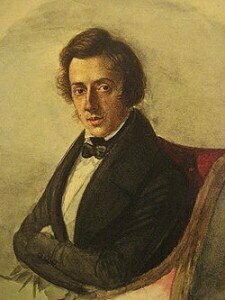

Frédéric Chopin

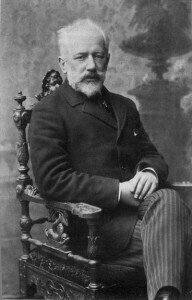

Completed in April 1893, the 18 Morceaux, Op. 72 were Tchaikovsky’s last works for solo piano. Putting together the relevant musical materials for a series of piano pieces he told his brother, “in order to earn some money, I will compose a few piano pieces and romances.” Initially, work progressed rather slowly, but “it’s remarkable that the further I get, the easier and more enjoyable the job becomes,” he writes. “The first two or three items were merely the result of an effort of will, but now I cannot stop my ideas, which appear to me one after another, at all hours of the day.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Originally Tchaikovsky had aimed at writing 30 pieces, but he finalized the set at 18. Apparently, Tchaikovsky had never been a great friend of Frédéric Chopin’s music, and biographers and oral historians suggested that Tchaikovsky “found in him a certain sickliness of expression, as well as an excess of subjective sensibility.” In his formal writings, Tchaikovsky had very little to say about the Polish composer, but the 15th of his 18 Morceaux was clearly conceived as a mazurka in the style of Chopin.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: “Un poco di Chopin,” from 18 Morceaux, Op. 72

Friedrich Kalkbrenner

Here is a bit of a trick question; who was considered the foremost pianist in Europe when the Polish composer Frédéric Chopin relocated to Paris? Since I’ve given you a bit of a hint already, you would be absolutely correct in your assumption that it was not Franz Liszt, but Friedrich Kalkbrenner (1785-1849). Born in Germany, Kalkbrenner studied at the Paris Conservatoire and eventually settled in Paris. Famous throughout Europe as swashbuckling piano virtuoso, he was also an investor and promoter in the Pleyel piano company. An astute businessman, Kalkbrenner established a “Factory for aspiring virtuosos,” drawing students from as far away as Cuba. When Frédéric Chopin first met Kalkbrenner in 1831, he was dazzled. “I am in very close relations with Kalkbrenner, the 1st pianist in Europe,” he writes, “all the other piano virtuosos in Paris, including Franz Liszt, are zero besides him.” In the winter of 1831, Chopin seriously considered becoming a Kalkbrenner student, writing “anybody who understands music must appreciate Kalkbrenner’s talents… I can assure you there is something superior about him, to all the virtuosi whom I have hitherto heard.” And on 16 December 1831, Chopin reports “I wish I could say I play as well as Kalkbrenner, who is perfection in quite another style to Paganini. Kalkbrenner’s fascinating touch, the quietness and equality of his playing, are indescribable; every note proclaims the master. He is truly a giant, who dwarfs all other artists.” Frédéric Chopin’s plans to study with Kalkbrenner came to naught, as he demanded a commitment of three years! Chopin eventually dedicated his first piano concerto to Kalkbrenner, who reciprocated by composing a couple of variation sets on Chopin themes.

Friedrich Kalkbrenner: Variations brilliants on a mazurka by Chopin, Op. 120

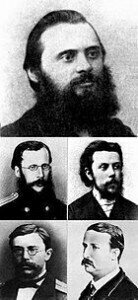

“The Mighty Five”

The Polish composer’s originality as a composer received a decidedly nationalist interpretation by Mily Balakirev (1837-1910) and his circle of “The Mighty Five.” For Balakirev, Chopin managed to integrate folk materials with the most advanced techniques of contemporary European art music. And it was precisely this fusion of nationalism and modernism that Balakirev attempted to promote. For him, “Chopin was neither a salon composer nor a romantic composer, but a radical, progressive figure.” Balakirev was introduced to the music of Chopin at an early age, and the celebration of his music became a preoccupation well into his twilight years. On the occasion of the Frédéric Chopin centenary in 1910, Balakirev produced his orchestral Chopin Suite, and re-wrote the second movement of Chopin’s E minor concerto for solo piano. A couple of years earlier, his friend Konstantin Tchernov had persuaded him to write down an improvisation on two Chopin Op. 28 preludes. The result was the Impromptu, modeled on Chopin’s E-flat minor and B Major Preludes.

Mily Balakirev: Chopin Suite, Op. 11 (Singapore Symphony Orchestra; Hoey Choo, cond.)

Mily Balakirev: Chopin – Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11: II. Romance (James Rhodes, piano)

Mily Balakirev: Impromptu (after Chopin’s Préludes) (Nicholas Walker, piano)

Heitor Villa-Lobos

In 1949, the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization, probably better known under the acronym UNESCO announced a project to pay tribute to the centenary of Frédéric Chopin’s death in 1849. It established the foundation of two scholarships in Paris for young Polish composers, and financed the publication of a complete catalogue of the recordings of Chopin’s works. In addition, it organized a concert consisting of compositions specifically written for the occasion by a number of prominent living composers. Held at the Salle Gaveau on 3 October 1949, the “Homage à Chopin” concert featured a series of ten chamber, vocal and instrumental pieces composed by Lennox Berkeley, Carlos Chavez, Oscar Esplà, Jacques Ibert, G.-F. Malipiero, Bohuslav Martinů, Andrzej Panufnik, Florent Schmitt, Alexandre Tansman, and Heitor Villa-Lobos. Villa-Lobos’ Hommage is cast in two movements, and addresses two musical forms intimately associated with Chopin. Despite some spiky Brazilian inflections, the “Nocturne,” elicits an almost timeless quality, and the highly idiomatic and stormy “Ballade,” is a rather sophisticated emulation of Frédéric Chopin’s style.

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Hommage à Chopin

I simply find his First concerto wonderful.