First things first, a symphonic poem is an orchestral composition, usually in a single continuous movement. Basically, the music of a symphonic poem attempts to communicate or carry meanings, messages, or concepts that originate from outside music itself. This can be a poem, short story, novel, painting, or other non-musical sources.

When instrumental music carries or conveys such non-musical information, it falls into a larger category called “Programme Music.”

© www.chosic.com

The famous pianist and composer Franz Liszt writes, “a programme is a preface added to a piece of instrumental music, by means of which the composer intends to direct the listener’s attention to the poetic idea of the whole or to a particular part of it.” On one hand, music can describe objects, like a flowing river by Smetana, narrating the story of an old Cossack fighting against repression, or tell the autobiographical journey of Hector Berlioz to Italy. However, Liszt also tells us that “Programme Music” can put the listener emotionally in the same frame of mind, as could the objects themselves.

Symphonic poems are interchangeably called tone poems, and that form flourished in the second half of the 19th century and in the early part of the 20th. Literally, hundreds of such symphonic poems were composed, and a scholar writes, “In many ways, it represents the most sophisticated development of instrumental programme music in the history of music.” I am sorry that I can’t mention them all. However, I can present to you some of the best symphonic poems of all time. Please don’t be upset if your favorite tone poem is not represented, but we are happy to have additional blogs based on your preferences and suggestions.

Paul Dukas: The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

Mickey Mouse as The Sorcerer’s Apprentice in Disney’s Fantasia

I am sure that many of you know one of the best symphonic poems of all time from the animated 1940s film “Fantasia.” The story of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” comes from a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and the music by Paul Dukas (1865-1935) depicts the magical events of Goethe’s poem. In fact, both Goethe’s poem and Dukas’ music have achieved worldwide recognition.

A brief musical introduction casts a mysterious and magical spell, as the old sorcerer leaves his workshop. Without warning, the trumpet sounds a forceful motif associated with the casting of a spell, and the introduction ominously grows in musical intensity. In due course, the marching broomstick theme cautiously emerges. Sliding scales, suggesting the flowing of water, gradually increase in dynamic level as the apprentice’s bath is beginning to overflow.

As the music is working towards an exhilarating climax, the shrieking apprentice, in futile desperation, seizes an axe and chops the broom in two. Instead of calming the situation, however, each segment becomes a new broom and the water is flowing at twice the speed. The broomstick theme is sounded in canon, and the music relentlessly accelerates in tempo and increases in dynamic level. Finally, we hear the return of the spell motif, signaling the return of the sorcerer, who quickly restores order.

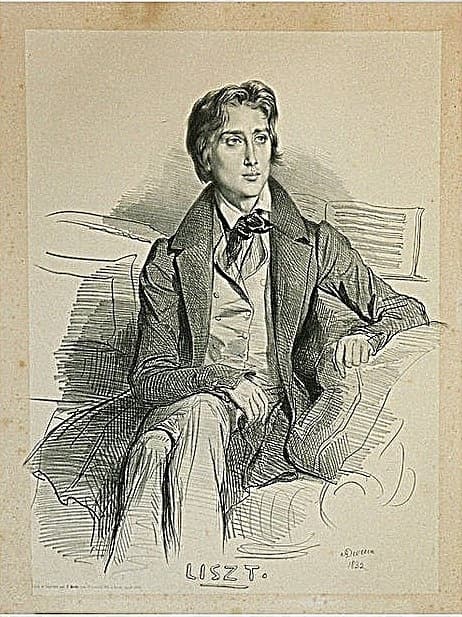

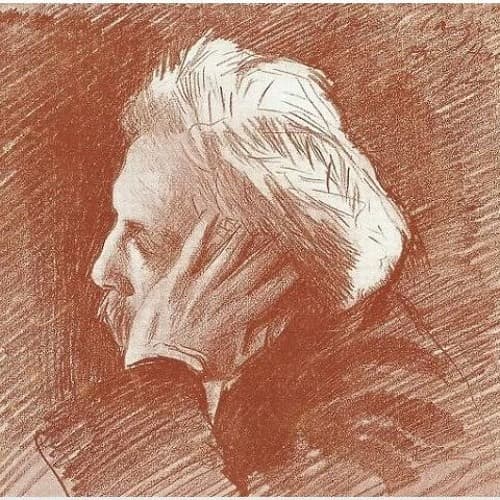

Franz Liszt: Mazeppa

Portrait of Franz Liszt, 1832

The Hungarian composer Franz Liszt (1811-1886) is considered the father of the symphonic poem, as he was the first to apply that title to 13 works in that form. Liszt was looking to write music with the complexity of a classical symphony but with the emotional impact of an opera. “Mazeppa” is based on the story of the Ukrainian Cossack Ivan Mazeppa, and his support of Sweden in his quest for Ukrainian independence from Poland and Russia. The work first appeared in a set of 12 piano pieces and was reworked several times before it became the symphonic poem Mazeppa.

The story tells of the Ukrainian nobleman Mazeppa who works at the court of the King of Poland. Mazeppa has a steamy love affair with the wife of a Polish Count and is punished by being tied naked onto a wild horse. The horse violently gallops towards Ukraine but eventually collapses. Mazeppa is saved by Ukrainian Cossacks who then name him as their leader. Under his leadership, the Ukrainian men gained major victories on the battlefield.

One of the best symphonic poems of all time, Mazeppa is divided into two specific sections. Section 1 is titled “Mazeppa’s ride,” and opens with an extended introduction. This is followed by a musical description of the hero’s journey through the vast steppes of Ukraine. The wild ride is sounded in restless strings, while the melody associated with “Mazeppa” is first sounded in the trombone. This theme is heard throughout the work, as the hero experiences differing situations and emotions. Depending on the emotions experienced, the theme is transformed and distorted, and six strokes of the timpani evoke Mazeppa’s fall. The second section opens quietly, as bassoon and horn soloists express astonishment that the hero is still alive. To the sounding of a march, Mazeppa and his Cossacks are placed in front of the army and the return of the hero’s theme signifies his end in glory.

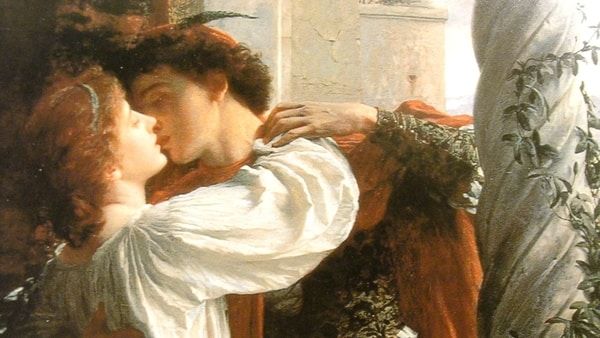

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Romeo and Juliet

Romeo and Juliet are surely the most famous lovers in history. The basic story dates back to antiquity, and Shakespeare borrowed heavily for his tragedy. That play is set in Verona Italy, and Juliet drinks a potion to put her into a deathlike coma to escape an arranged marriage. Romeo, her lover, never gets the message that it is simply a ruse, and he finds his love lifeless in the family crypt. Overcome with grief Romeo drinks the poison, and when Juliet awakes and discovers that Romeo is dead, she stabs herself with his dagger.

The tragic death of the two young lovers ultimately reconciles their feuding families. This tragic and most famous love story ever written also found its way into countless musical settings.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) composed three different versions of his Romeo and Juliet, but he did not want to title it a symphonic poem but rather a “Fantasy-Overture.” The final version was finished in 1880 and first heard in public in 1886. Tchaikovsky uses musical themes to symbolize characters and events, including the conflict between the Capulets and the Montagues, Friar Laurence, the love between Romeo and Juliet, and the battle between the two families. Very specifically, the French horns symbolize Romeo and the flutes represent Juliet.

One of the best symphonic poems of all time, Tchaikovsky’s music centers on the battle between the feuding families. You can certainly hear the musical fighting towards the end, and it provides the tragic climax to the work. The love theme, first sounded in the horn and viola, and later in the clarinet, carries significant meaning. The music sounds entirely pure and at peace, and while we know that their love is doomed, Tchaikovsky infuses this theme with an eternal sounding quality. It is beautifully seductive yet simultaneously tragic music that mirrors the trials and tribulations of Tchaikovsky’s personal life.

George Gershwin: An American in Paris

George Gershwin

When George Gershwin (1898-1937) came to Paris in 1926 he was looking to expand his musical horizon by taking lessons with Maurice Ravel. Ravel excused himself under the pretense of not “wanting to spoil Gershwin’s musical voice,” and he referred him to Nadia Boulanger, who also refused to tutor him. Undeterred, Gershwin met up with Stravinsky, Milhaud, and Auric, and he certainly soaked up the exciting atmosphere of the Parisian capital. His brother Ira wrote in his diary, “George is spending considerable time networking, sharing his progress with composers and publishers. He is mingling with composers and artists from across Europe.”

Looking to transfer his impression of the French capital into music, Gershwin worked feverishly on his “Tone Poem for Orchestra” titled An American in Paris. The composer writes, “My purpose is to portray the impressions of an American visitor in Paris as he strolls about the city, listening to the various street noises, and absorbs the French atmosphere.” You can certainly hear that special atmosphere in Gershwin’s orchestration. It is scored for the standard instruments of the symphony orchestra, but also includes celesta, saxophones, and automobile horns.

Gershwin immediately introduces us to the two main “walking themes,” accompanied by the bustle of the city and blaring taxi horns. In the contrasting middle section, Gershwin introduces the American Blues and a sense of being homesick. The return to the opening recapitulates the walking themes, but the stroll concludes with the slow blues theme.

The composer called it “the most modern music I’ve yet attempted,” and it is certainly one of the best symphonic poems of all time.

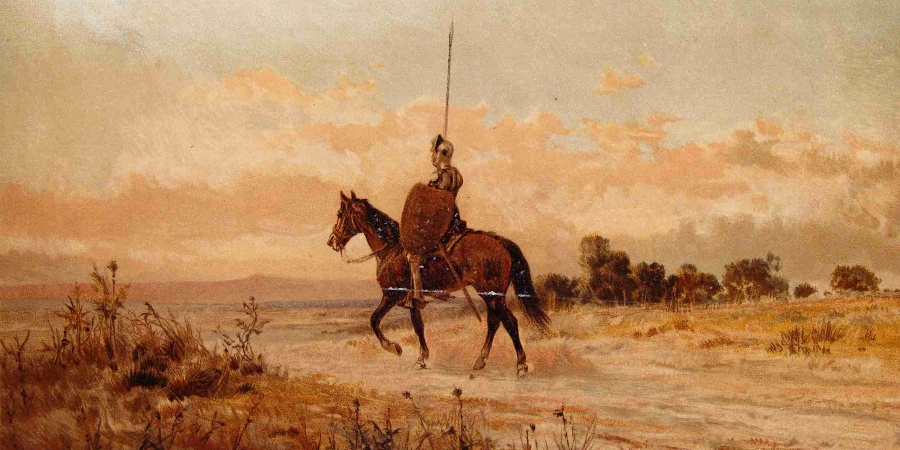

Richard Strauss: Don Quixote

Don Quixote © flickr.com

The Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes found his personal hero in a 16th century Spanish noble who leaves home to right the ills of the world. “Don Quixote de la Mancha” is a bumbling knight who is unable to separate reality from fiction. He takes up his lance and sword to defend the helpless and destroy the wicked, and in the process aids damsels in distress and battles giants, mostly in his own head. The adventures of Don Quixote and his supporting characters have inspired a flood of musical interpretations, among them the magnificent and well-known tone poem by Richard Strauss.

Richard Strauss (1864-1949) composed his monumental tone poems during a ten-year period from 1888 to 1898. A scholar writes, “Fusing the sheer force of his imagination with his embrace of an aesthetic of programme music that denounced tradition, and abstract musical form as obsolete, Strauss crafted the central musical expressions of the Austro-German tradition at the turn of the century.” In his musical representations, Strauss reveals himself as a composer “capable of making poet content and formal design coalesce with great brilliance.”

Don Quixote is, without doubt, the most obviously descriptive and picturesque of Strauss’ symphonic poems. The solo cello represents “Don Quixote,” and his sidekick “Sancho Panza,” can be heard in the bass clarinet and tenor tuba. The horse “Rosinante” is suggested by motives sounded in the solo viola. Strauss wrote 10 fantastic variations, prefaced by a prologue. In due course, the three main musical themes, including the dreamy oboe melody representing “Dulcinea,” are ingeniously transformed and combined, and heard as a succession of musical tableaux depicting episodes from the story. From the famous attack on a group of windmills and the deathly battle with a herd of sheep to his final defeat by the Knight of the White Moon, no composer has ever had a “fuller understanding or captured more facets of Don Quixote’s personality than Richard Strauss.”

Ottorino Resphighi: Pines of Rome

When Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) was appointed professor of composition at the prestigious Conservatory of Santa Cecilia in Rome in 1913, he produced two symphonic poems that brilliantly evocate the Eternal City. Respighi wrote, “In these symphonic poems the composer has endeavored to give expression to the sentiments and visions suggested to him by pine trees in four locations contemplated at the hour in which their character is most in harmony with the surrounding landscape, or in which their beauty appears most impressive to the observer.”

The four-movement symphonic poem The Pines of Rome is scored for large orchestra, including organ and augmented brass. Performed continuously, it musically depicts pine trees located in different areas around the city of Rome. “Pines of the Villa Borghese” portrays children playing among the pine groves on a sunny afternoon. In the central section, highly reminiscent of Debussy, a carriage drawn by trotting horses momentarily disrupts the children’s nursery rhyme.

The children suddenly disappear in “The Pines near a Catacomb” as the shadows of the trees cover the entrance to the subterranean chambers. Gloomy strains of ancient plainsong suggest the hidden nature of the catacombs, while the trombones and horns represent priests’ chanting. “The Pines of the Janiculum” reflects silvery moonlight, as the remote song of a nightingale sounds in the distance. As dawn rises over “The Pines of the Appian Way,” the music recalls the past glories of the Roman Republic, as the brilliance of the newly rising sun is reflected in the armor and weaponry of a triumphant Roman legion advancing along this famous historic road.

Claude Debussy: Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun

Édouard Manet: Frontispiece for L’après-midi d’un faune (1876)

Allow me to conclude this blog on the best symphonic poems of all time with one of my personal favorites. In his youth, Claude Debussy was strongly influenced by poetry and literature, and not necessarily music. Above all, it was the language of poetry that fueled his imagination. Much has been written about “Prélude à L’après-midi d’un faune” with regard to Mallarmé’s extended poem and Debussy’s musical setting. Many people still read the score as a direct parallel to Mallarmé’s poem.

Debussy would have none of that, as he wrote 2 years after the premiere of the work. “The “Prélude à L’après-midi d’un faune” might it be what remains of the dream at the tip of the faun’s flute? More precisely, it is a general impression of the poem, for if the music were to follow more closely it would run out of breath.” This is exactly what Liszt had in mind, remember? He wanted to put the listener emotionally in the same frame of mind, as could the object itself. To be sure, although the number of lines of the poem is identical to the number of measures in the score, it is clearly not a word-by-word translation.

Instead, the music captures the delicious vagueness of contours, remaining entirely unpredictable and reflecting the unconstrained nature of the faun’s meditations. The orchestral flute is given a solo part throughout, and unsurprisingly, the instrument sounds a languid opening melody that gradually unfolds to include an increasingly intense orchestral accompaniment. Clarinet and oboe temporarily take over the initiative, and as the music accelerates, the opening flute theme reappears in a highly chromatic guise. Eventually, the music settles into a serene and peaceful idyll, and the composer and conductor Pierre Boulez claimed, “Modern music was awakened by L’après-midi d’un faune.” I hope I have awakened your interest in the best symphonic poems of all time, and please let us know in the comments which other works you’d like to see featured in the future.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Firstly, I could omit the Gershwin as for me it’s in a totally different category.

With Strauss, I would substitute Ein Heldenleben for Don Quixote.

The others are excellent choices, and I would add the following:

Franck – Le Chausser de Maudit.

Sibelius – Nightride and Sunrise.

Delius – A Song of Summer.

Vaughan Williams – Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1.

Honegger – Pastorale d’Ete.

With a due respect, I must disagree with your wanting to eliminate American in Paris and wanting to place it in a different category (which category?). This piece has all the ear markings of any other tone poems, the sights and sound are right there. It is, for sure, in a more modern setting than most that are discussed here.

The beauty of critiquing classical music is certainly subjective and we all have that freedom.

Fine list. My preference would be Tapiola for Night Ride , though N Ride is great.

Also would add Dvorak Wood Dove.

Any list of great symphonic poems must include several by Liszt, its brilliant inventor.

Les Preludes, Tasso, Prometheus, Mazeppa, Hamlet, From the Cradle to the Grave, Orpheus.

Some other great tone poems:

Dvorak: The Water Goblin & Golden Spinning Wheel

Tchaikovsky: The Tempest

Saint-Saens: Danse Macabre, Phaëton

Sibelius: Pohjola’s Daughter