Over a period of about 22 years, Ludwig van Beethoven composed a total of eleven overtures for a variety of occasions and under different circumstances. Overtures had traditionally served as openings for stage or larger vocal works for centuries. Although they were frequently called “Sinfonia” or “Sinfonie” well into the 18th century, they had nothing to do with the symphony. An entry in a musical dictionary of 1802 explains, “The now more common introductory movements to large vocal pieces, which are called overtures, have an undefined and arbitrary form; they are generally given a form identical or similar to the first Allegro of the symphony. The overture’s character is also indeterminate, and generally conforms to the character of the vocal piece to which the overture serves as introduction.”

Ludwig van Beethoven © coloradosymphony.org

Beethoven wrote four overtures for various performances and versions of his opera Leonore/Fidelio, and three for festivals opening new theatres. These festival overtures are similar to the overtures to Egmont and Prometheus as “they constitute only the first part of more extensive incidental music.” However, the overture to Coriolan, originally attached to a play, developed a life of its own and might well be considered one of the first concert overtures. But let’s start at the beginning, and with The Creatures of Prometheus.

Ludwig van Beethoven: The Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43 “Overture”

Prometheus, so it is told in Greek mythology, gave humanity the gift of fire. That creative spark gave humankind the ability to run its own affairs, and it awoke a consciousness that once only belonged to the gods. Humans were now in charge of their own destinies, relying on courage, cunning, ambition, speed, and strength to perform incredible deeds, battle fierce monsters, and establish great cultures that changed and shaped the world. Beethoven was shaping his world in Vienna in 1800 when he received the commission to compose music for the ballet The Creatures of Prometheus.

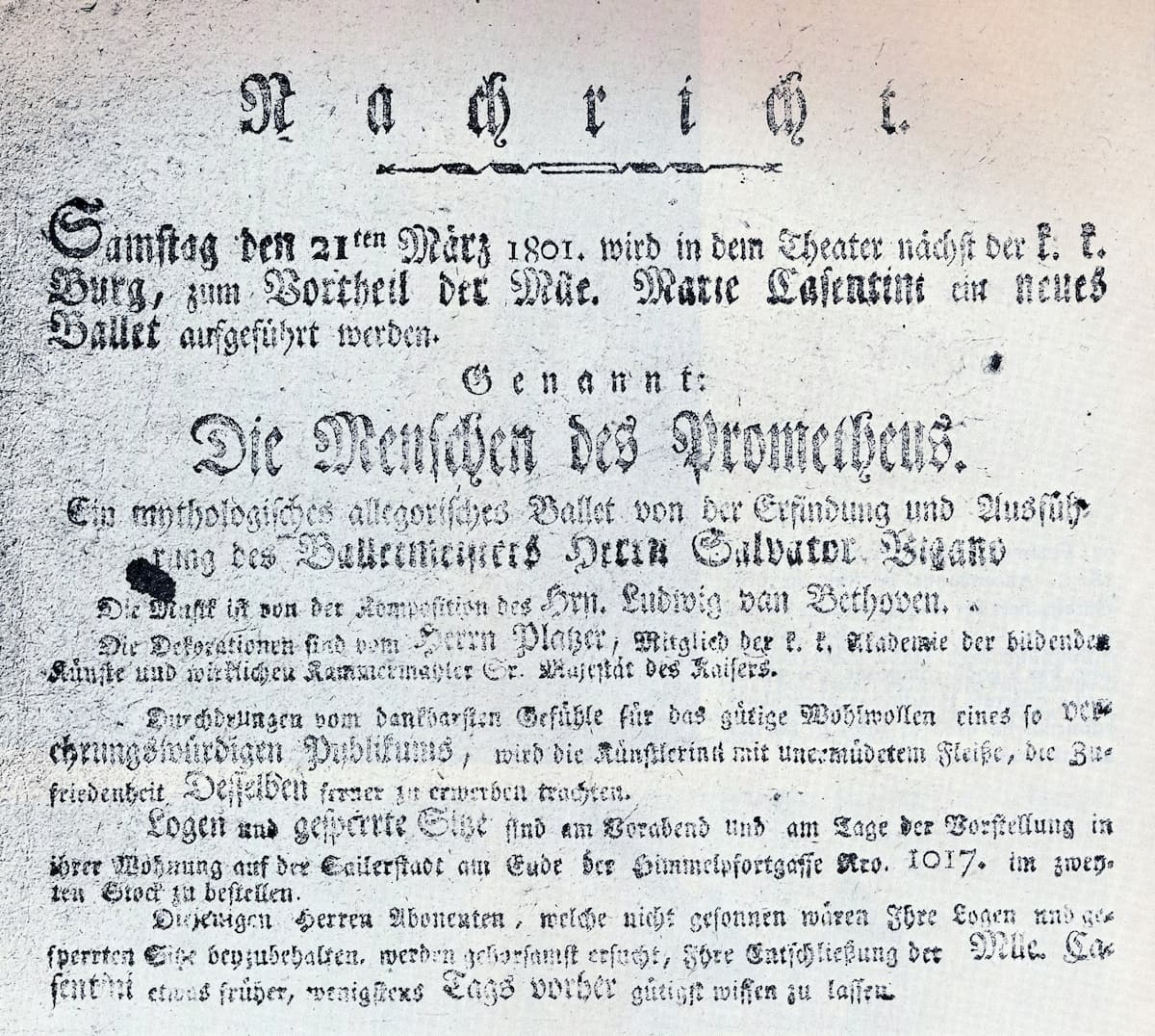

Playbill for the ballet performance of The Creatures of Prometheus

The production premiered in March 1801 and was moderately successful. It ran for 20 performances during its first season and for 13 during the second. For reasons still unknown, the ballet completely disappeared thereafter, and the original text and choreography are lost. The overture was published in 1804 and quickly acquired an independent life. To this day, it remains the only part of the ballet—although some reconstructions have been attempted—that is performed as a stand-alone composition.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Leonore Overture No. 2, Op. 72b

Leonard Bernstein called Beethoven’s only opera Fidelio “one of his greatest works, containing some of the most glorious music ever conceived by a mortal, one of the most cherished and revered of all operas, a timeless monument to love, life, and liberty, a celebration of human rights, of freedom to speak out, to dissent. It’s a political manifesto against tyranny and oppression, a hymn to the beauty and sanctity of marriage, an exalted affirmation of faith in God as the ultimate human resource.”

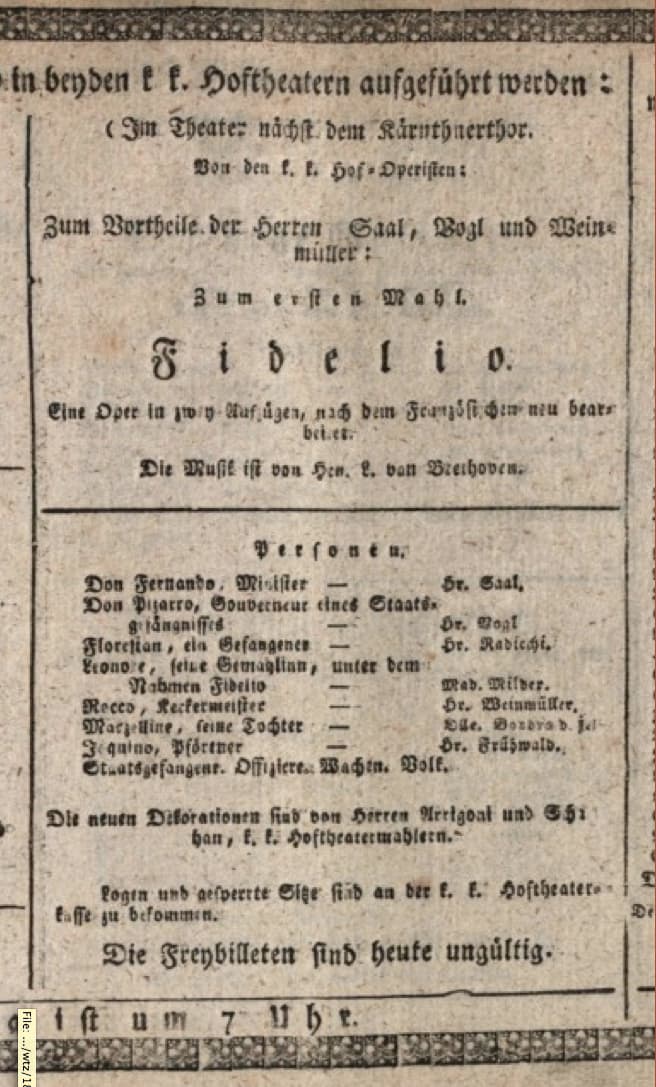

Playbill of Beethoven’s Fidelio, 1814

Reading Bernstein’s description it is unsurprising that Beethoven struggled with the opera for almost ten years, producing three versions and composing four different overtures. The three discarded overtures are known under the original title of the opera, Leonore. When the first version of the opera premiered to a rather lukewarm reception in 1805, audiences were treated to the Leonore Overture No. 2, basically a miniature tone poem that outlines the entire plot of the opera.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72a

Beethoven revised his opera in 1806 and composed a brand new overture, his Leonore Overture No. 3. You are most likely to hear this particular overture in concert today. It is a grand affair, with the essence of the entire opera transmitted in a mere 15 minutes. The opening sounds a musical image from Florestan’s dungeon, succeeded by a quotation from his gigantic second-act aria, which quickens, is richly developed, and then cut off by a trumpet call signifying his liberation. This leads to a passage suggesting Florestan’s realization that it is Leonore who is responsible for freeing him. The overture ends in a jubilant celebration of freedom and conjugal love. Gustav Mahler inserted this overture between the two scenes in Fidelio’s second act, but Beethoven must have realized that this overture, very close in expression to a tone poem, severely overpowered the opera.

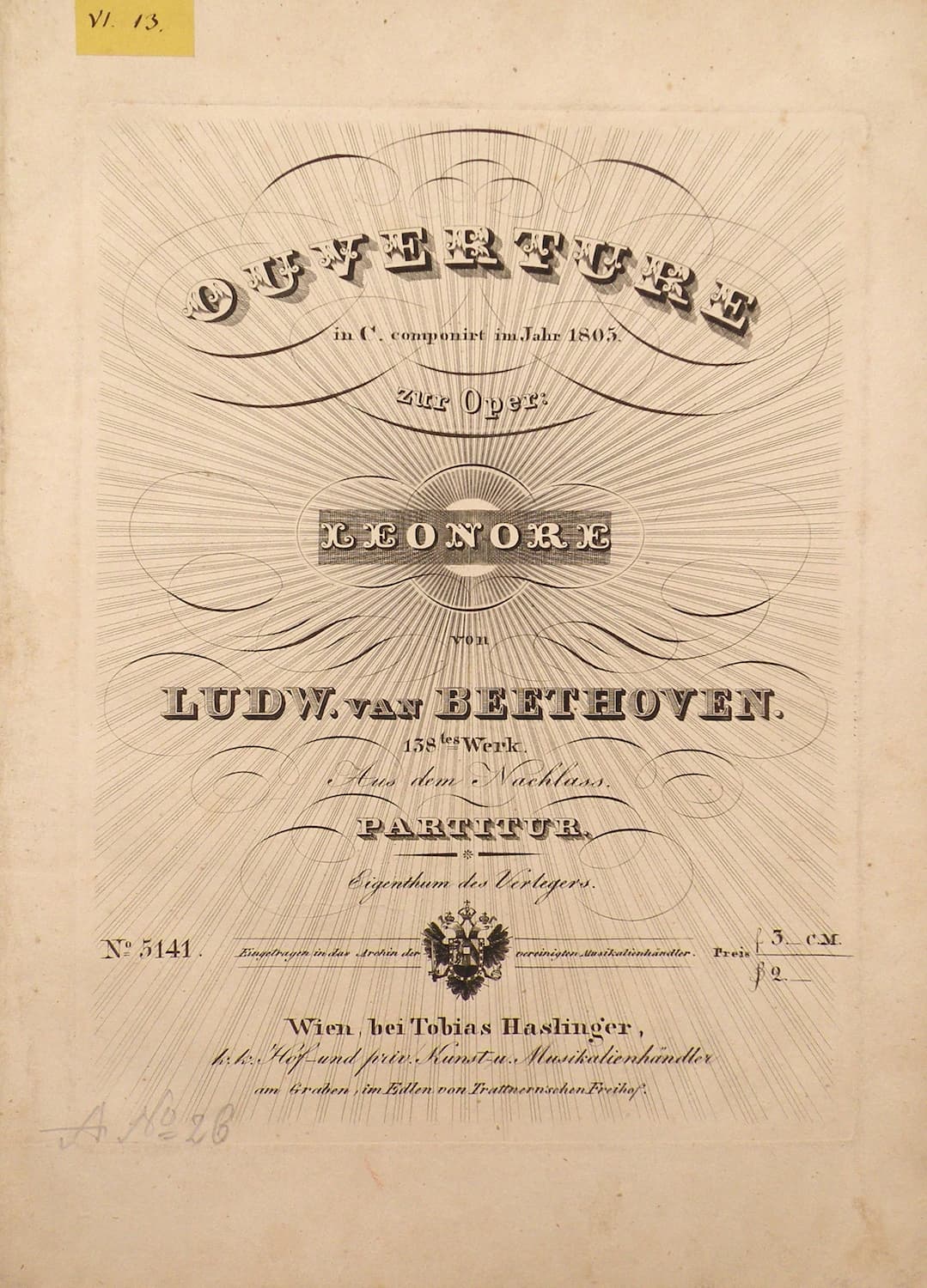

Ludwig van Beethoven: Leonore Overture No. 1, Op. 138

In 1808 Beethoven was preparing his opera for a performance in Prague, and he once again rethought his overture. Leonore No. 3 is an intensely dramatic and full-scale symphonic movement that easily overwhelms the rather light initial scenes of the opera. As such, Beethoven scaled back on the dramatic weight of Leonore 2 and 3 and composed his Leonore No. 1.

Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 1 Op. 138

Commentators have suggested that the “sweepingly virtuosic violin lines seem to anticipate later overtures by Carl Maria von Weber.” In the event, the performance in Prague never took place and the score was first published only in 1838.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Fidelio, Op. 72 “Overture”

When the final version of Fidelio sounded in 1814, it was prefaced by a brilliant curtain-raiser overture that no longer overpowers the stage. The Fidelio Overture no longer uses any of the musical themes heard in the opera, and Beethoven later told his friend Anton Schindler, “Of all my children, this is the one that cost me the worst birth-pangs and brought me the most sorrow; and for that reason, it is the one most dear to me.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Namensfeier Overture, Op.115

Ludwig van Beethoven always thought of his overtures as functioning within a ceremonial or dramatic frame. The various versions of his Leonore Overture, as we have seen, served as introductions to operatic entertainment, and Wellington’s Victory patriotically celebrated the defeat of Napoleonic forces. More practical reasons seem to have guided Beethoven’s decision to begin work on an overture in honor of the “Name Day” of Emperor Franz I of Austria. Having lost much of his popularity with the Viennese public, Beethoven apparently hoped that an overtly patriotic composition performed in front of a large public gathering, would rekindle his personal fame.

Joseph Kreutzinger: Portrait of Kaiser Franz I

The Namensfeier Overture was scheduled for performance on October 4, 1814. However, Beethoven was not able to complete the piece in time, with the eventual premier taking place on December 25, 1815. The music is predictably bombastic and sentimentally lyrical and concludes with a rhythmically uneven coda. This stand-alone overture would readily fit within the frame of a concert overture, but sadly, it is “considered one of Beethoven’s least successful orchestral compositions,” and therefore not performed with any kind of regularity.

Ludwig van Beethoven: The Consecration of the House, Op. 124

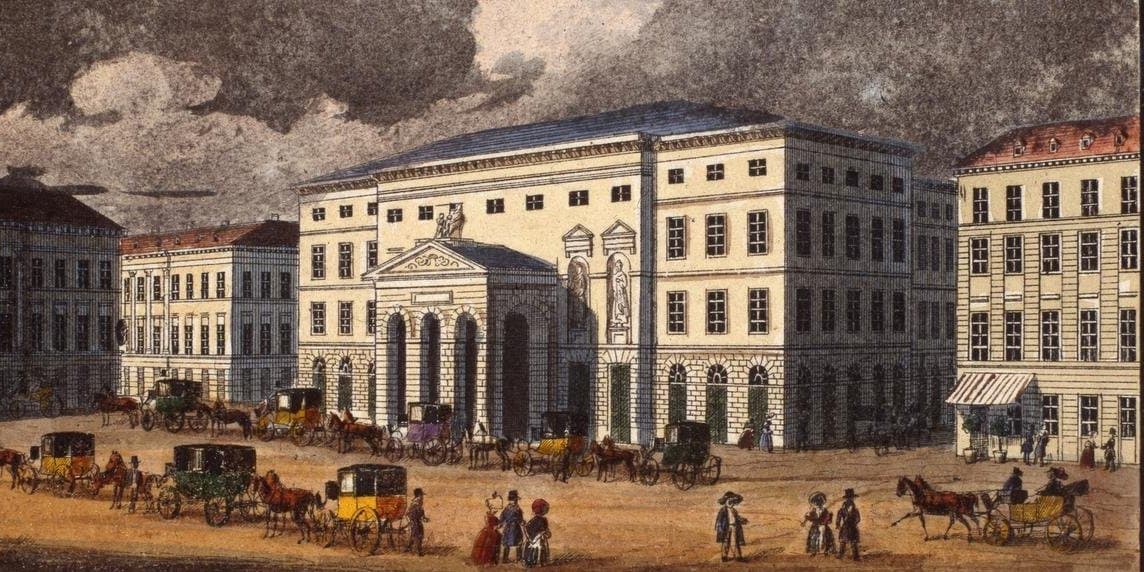

On 3 October 1822 the “Theater in der Josefstadt” reopened its doors to the Viennese public. On very short notice, Director Carl Friedrich Hensler decided to commission Beethoven to compose music for “The Consecration of the House.”

Interior of Theater in der Josefstadt

Supposedly, Beethoven conceived two themes for this overture while on a walk and told Anton Schindler “that he intended to treat one of these themes in a contrapuntal fashion after Handel.

Ludwig van Beethoven: The Ruins of Athens, Op. 113 “Overture”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Die Ruinen von Athen (The Ruins of Athens), Op. 113 – Overture (Cappella Aquileia; Marcus Bosch, cond.)

In order to meet the deadline, Beethoven revised the incidental score for The Ruins of Athens slated for the dedication of a new theatre in Pest in 1811. It was to feature two new components, a pair of festive overtures that paid homage to the great masters J. S. Bach and George Frideric Handel. As we can readily hear, only the Handel tribute came to fruition.

German Theatre in Pest

The work is heard somewhat infrequently today, but it is one of just three large orchestral works composed by Beethoven during his final decade. As a commentator writes, “In manner, ethos, and affect, the overture reflects much that was visionary and new in Beethoven’s approach to composition at that time.” As such, it is hardly surprising that it also opened the benefit concert on 7 May 1824, during which his Ninth Symphony was premiered.

Ludwig van Beethoven: King Stephen, Op. 117 “Overture”

The aforementioned overtures for “The Ruins of Athens” and “King Stephen” are based on theatrical plays by August von Kotzebue. The former is a powerful piece of political and cultural propaganda. In the play, the goddess Athena awakes from a 2000-year slumber to find Athens in a deprived state, having been taken over by the Ottoman Empire. With the assistance of Hermes, Athena joins Franz I at the opening of Pest’s new theater in celebration of the triumph of the muses of comedy and tragedy, Thalia and Melpomene. Athena crowns a bust of Franz I, erected by Zeus, and Hungary takes its place as the new Athens. The plays were written to commemorate the opening of a magnificent new theater in the Hungarian city of Pest on the banks of the Danube. The theater’s construction was funded by Franz I, the last Holy Roman Emperor and the first emperor of Austria, as a way of politically unifying Hungary with the interests of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy. Beethoven received the commission in 1811, and quickly composed the overture while taking a rest at the Bohemian spa of Teplitz. “Beethoven transformed the play into a virtual operetta or Singspiel and wrote enduring and popular music of the highest quality.”

August von Kotzebue

August von Kotzebue (1761-1819) was a German lawyer, political journalist, and a government official in Estonia. He was a prolific playwright, magazine editor, and cultural journalist who ended up being assassinated in Mannheim by a theology student who suspected him of being a Russian spy. His murder served as the pretext to issue the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819, which cracked down on the liberal press and seriously restricted academic freedom in the states of the German Confederation. Kotzebue’s short play King Stephen served as the prologue for the lavish celebrations of the opening of the new theater in Pest. Initially, the author had written a trilogy of short plays on Hungarian subjects, but the middle one was censored for political reasons and replaced. King Stephen I was the national hero of Hungary, sainted for his efforts to Christianize the country in the 11th century. Kotzebue’s little play begins as a tribute to this historical figure but diverges into the politically sound celebration of the current Emperor, Franz I, and his wife. In his music, Beethoven made sure to incorporate Hungarian flavors. Two of the principal themes reflect Hungarian folk styles. “Both display what period listeners would have heard as Magyarisms, the first (andante con moto, introduced by the flute) through the ornament on the first note, the second (a presto section that begins a minute into the piece) through its vivacious syncopations.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Egmont, Op. 84 “Overture”

For the remaining two Beethoven overtures we turn once more to the theatrical stage. Count Egmont (1522–68), immortalized in Goethe’s tragedy of 1788, was an actual historical figure. In his struggle for Dutch liberty against the autocratic imperial rule of Spain, the Catholic loyal Count Egmont pleads for tolerance from the Spanish King. Philip II of Spain is not amused, and Egmont is arrested, imprisoned, and sentenced to death. When his mistress Klärchen fails to free him, she poisons herself and commits suicide. Before his own death, Egmont delivers a rousing speech and he dies in the knowledge that the rebellion is in progress and that his people will be free.

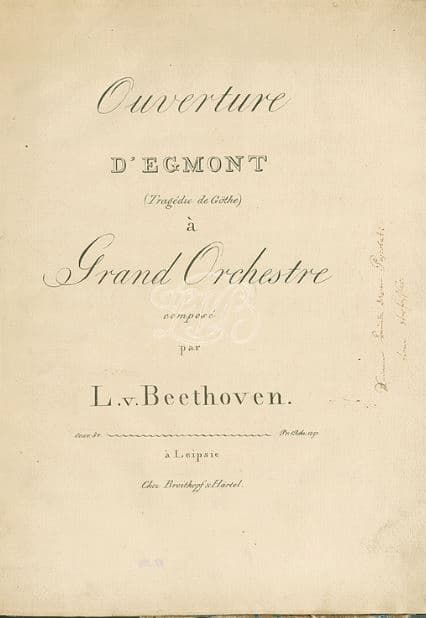

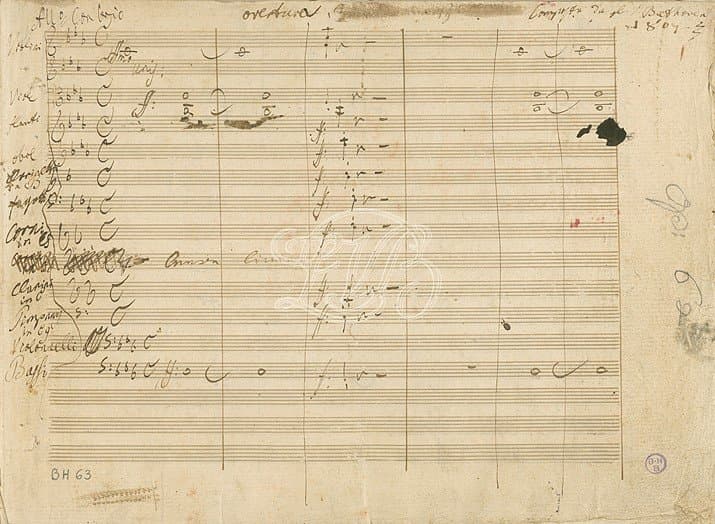

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture first edition © Beethoven Haus Bonn

Beethoven’s music for the play consists not only of the frequently performed overture, but also features a sequence of nine pieces for soprano, male narrator, and full symphony orchestra. The music was greeted with high praise, and Goethe himself declared that Beethoven had expressed his intentions with “a remarkable genius.” The music for the overture summarizing the drama begins in a somber and serious mood. Portraying oppression and darkness, the ominous slow introduction reveals a musical motif associated with the tyrant. That motif returns throughout before a brilliant coda rousingly transforms tragedy into triumph. Goethe’s play retained its place in the theatrical repertoire, as did Beethoven’s Overture on the concert stage.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Coriolan, Op. 62 “Overture”

Ludwig van Beethoven’s overture to Heinrich von Collin’s play Coriolan is of special interest. Collin’s play is based on the less frequently performed tragedy Coriolanus by Shakespeare, and it enjoyed some moderate success on the Viennese stage after its creation in 1802. The plot unfolds in ancient Rome. General Coriolan, angered at being banished from the capital for disregarding the people’s wishes, allies himself with Rome’s enemies. When, however, the besieged city threatens to fall, both his mother and his wife prevent him from conquering his native city. Conflicted between the love of country and desire for revenge, between reason and erupting emotions, he finally commits suicide. Collin’s play quickly faded from view, but the author attempted to resurrect his work in 1807 by commissioning Beethoven to write an overture to his drama.

Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture © Beethoven Haus Bonn

The play with Beethoven’s overture featured for a single performance at the palace of Beethoven’s patron Prince Lobkowitz. Soon thereafter, the play completely disappeared but Beethoven’s overture soon sounded independently. “The music was no longer attached to the performance of the drama, and had thus lost its original function as an introduction.” The overture was issued in print at the end of 1807, and “performed several times as an independent concert piece during the 1807/08 season.” It is still not entirely clear if the independent concert overture was the result of the composer’s intentions or a mere byproduct of Beethoven’s rapidly growing popularity. Either way, the Beethoven overtures stand at the cusp of a musical and historical discourse that shaped much of the musical narrative in the 19th century and beyond.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

FANTASTIC .

A lover of Beethoven for over 60 yrs