During his long performing career, the Polish-American violinist and composer Samuel Dushkin (1891-1976) was never considered a flashy virtuoso violinist but rather a highly respected musician. In his recordings, Dushkin reveals a powerful vibrato on the lower strings. Possibly attributed to the properties of early electric microphones, Dushkin produced a rather thick sound that became clearer and cleaner in the high register.

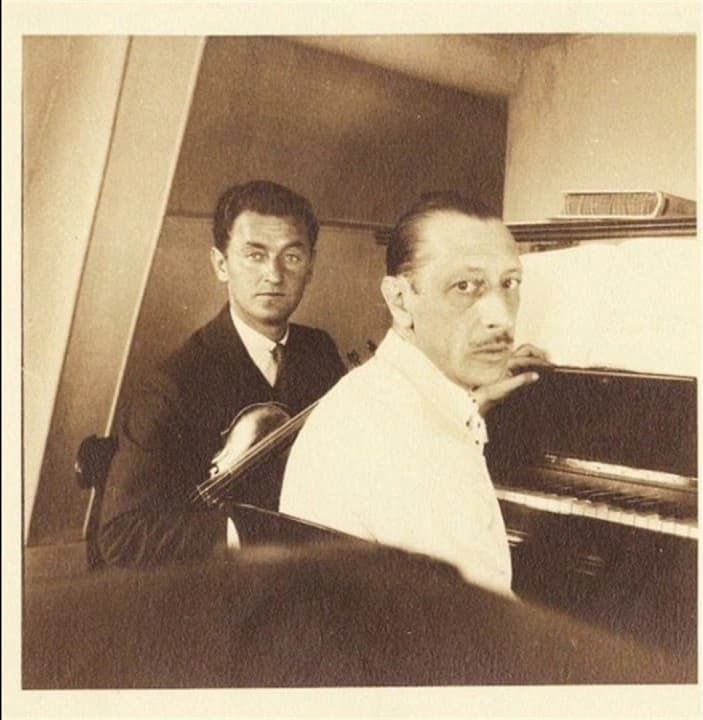

Samuel Dushkin and Igor Stravinsky at the piano

Dushkin, born in Poland, came to the USA at an early age and eventually became a protégé of the American composer and diplomat Blair Fairchild. Dushkin was sent to the Paris Conservatoire for instruction, and he also studied with Leopold Auer and was proud to be one of only two official students of Fritz Kreisler.

Samuel Dushkin: “Sicilienne,” (attributed to Maria Theresia von Paradis)

Dushkin started an extensive European tour in 1918, and he followed up with a tour of the United States in 1924. Like other violinists of his time, Dushkin published and performed a substantial number of arrangements and transcriptions for violin and piano. Among them was a “Sicilienne for strings and clavier” attributed to the blind musician and composer Maria Theresia von Paradis.

Paradis was a close friend of Mozart and well acquainted with Haydn, Salieri, and Gluck. As a composer, she wrote works for the stage, cantatas, songs, and a number of instrumental works for the piano. Her most famous composition, the lovely “Sicilienne,” however, is a musical hoax by Samuel Dushkin. Based on the Larghetto movement from Carl Maria von Weber’s Violin Sonata in F major, Op. 10, No. 1, Dushkin only took credit as the editor after having “discovered” this unknown composition.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: 2 Pieces, Op. 6, No. 2 “Hungarian Dance” (arr. S. Dushkin) (Hideko Udagawa, violin; Konstantin Lifschitz, piano)

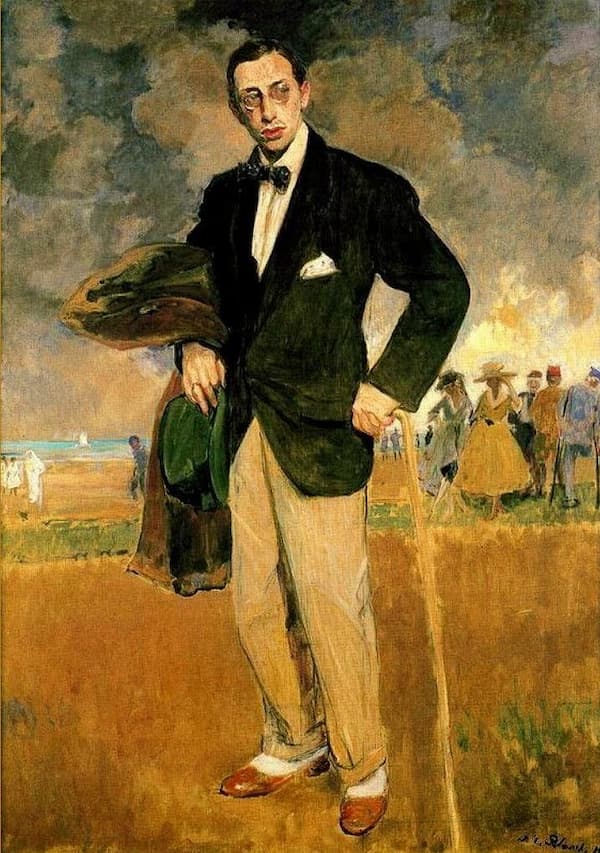

Igor Stravinsky

Dushkin supposedly found the “Paradis” piece in the 1920s but was never able to produce a manuscript to substantiate his claim. Composed in a romantic idiom and harmonic style, the “Sicilienne” is incompatible with the classical musical language von Paradis would have known. Paradis certainly never mentioned it among her works, and Dushkin never admitted his authorship.

Maybe you heard this little prank performed as part of the royal wedding celebration of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle? The exact motivation for producing these hoaxes is unclear, but he certainly might have learned a thing or two from his teacher, Fritz Kreisler. By choosing lesser-known composers, these works didn’t initially raise the red flags that might be expected in the case of an attribution to Haydn or Mozart.

Igor Stravinsky: Violin Concerto “Toccata”

Besides crafting musical hoaxes and transcriptions of works by other composer, Dushkin was a forceful advocate of contemporary music. And that is borne out in his collaborations and friendship with Igor Stravinsky. After the horrific carnage of World War I, Stravinsky was striving for a new sense of clarity, tranquillity, and objectivity. Stravinsky was not a violinist, and apparently hated virtuoso performances, criticising “their need for seeking immediate triumphs in the music.” However, all that changed when he met Samuel Dushkin in Paris in 1930.

To embark on a violin concerto was still a different kettle of fish altogether, and he first consulted his good friend Paul Hindemith. “I asked whether the fact that I did not play the violin would inevitably be to the disadvantage of my composition. He reassured me by saying that, on the contrary, he thought it would help me to avoid a routine technique and would give rise to ideas that would not be suggested by the familiar movement of the fingers.”

Igor Stravinsky: Violin Concerto “Aria 1”

Stravinsky frequently met Dushkin in Paris and one day wrote down a chord and asked the violinist if it could be played. Dushkin recalls, “I had never seen a chord with such an enormous stretch, and said no.” Stravinsky supposedly replied, “what a pity,” but Dushkin tried out the chord at home and found that “in that register the stretch of the eleventh was relatively easy to play, and the sound fascinated me.”

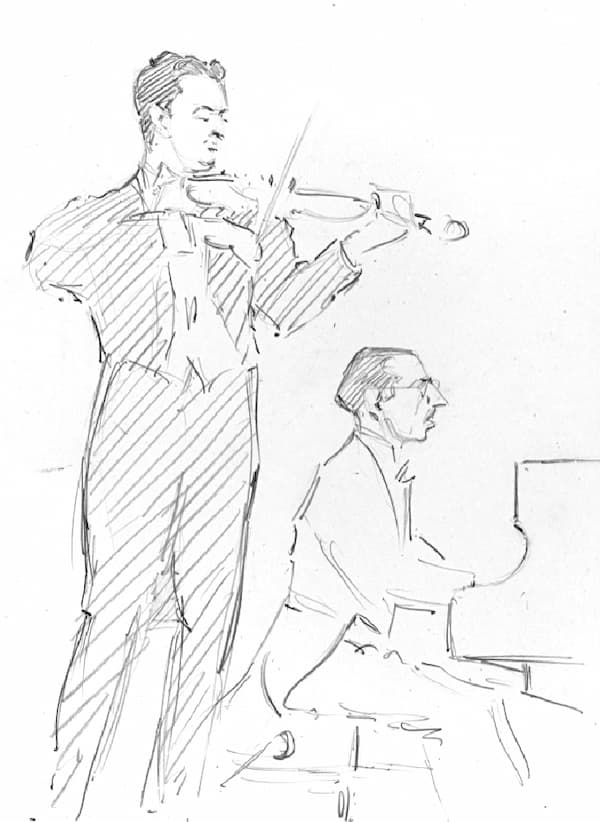

Samuel Dushkin and Igor Stravinsky

He quickly phoned Stravinsky and told him that it could be done, and once the concerto was finished six months later, that chord begins each of the four movements. Stravinsky called it “his passport to that concerto.” Stravinsky presented musical ideas and Dushkin offered technical suggestions. As Dushkin recalled, “Whenever he accepted one of my suggestions, even a simple change, Stravinsky would insist on altering the very foundations correspondingly. He behaved like an architect who if asked to change a room on the third floor had to go down to the foundations to keep the proportions of the whole structure.”

Igor Stravinsky: Violin Concerto “Aria II” (Isaac Stern, violin; Columbia Symphony Orchestra; Igor Stravinsky, cond.)

Dushkin premiered the Stravinsky Violin Concerto in a live broadcast from Berlin on 23 October 1931, with Stravinsky conducting. Dushkin also gave the work’s first US performance in January 1932, with Serge Koussevitzky conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Not to be outdone, he also made the first recording of the piece in 1935, with Stravinsky conducting once more.

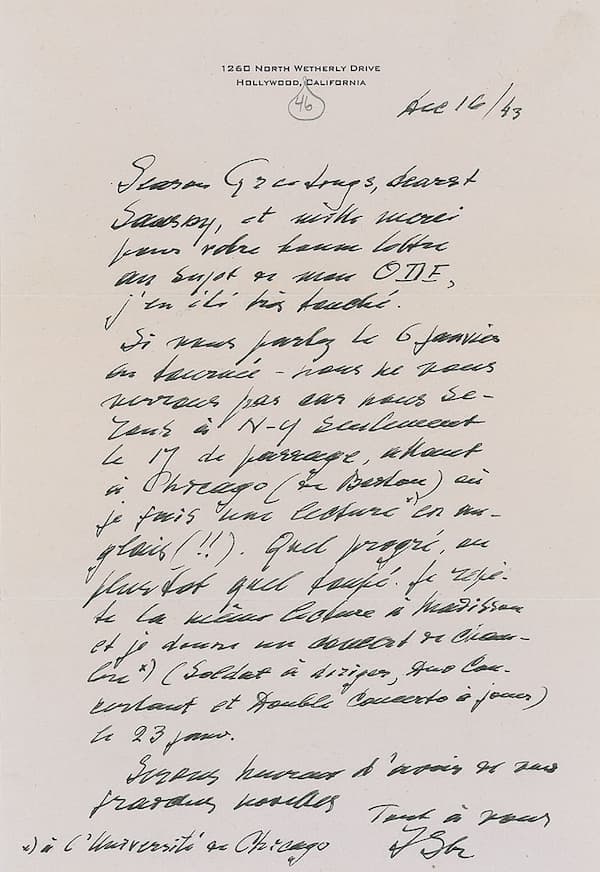

Stravinsky’s letter to Samuel Dushkin

In his autobiography, Stravinsky praised Dushkin’s “remarkable gifts as a violinist and referred to his delicate understanding and, in the exercise of his profession, an abnegation that is very rare.” And it was clear that the violin concerto was not the end of the collaborations but the beginning. Stravinsky writes, “Far from having exhausted my interest in the violin, my concerto, on the contrary, impelled me to write yet another important work for that instrument.”

Igor Stravinsky: Violin Concerto “Capriccio”

Stravinsky openly admitted that he did not have a great liking for the combination of piano and strings, “but a deeper knowledge of the violin and close collaboration with a technician like Dushkin had revealed possibilities I longed to explore. Besides, it seemed desirable to open up a wider field for my music by means of chamber concerts, which are so much easier to arrange, as they do not require large orchestras of high quality, which are so costly and so rarely to be found except in big cities.”

Apologetically, Stravinsky came up with the idea of writing a sort of sonata for violin, later to be called Duo Concertante. The composer explained, “I had taken no pleasure in the blend of strings struck in the piano with strings set in vibration with the bow. In order to reconcile myself to this instrumental combination, I was compelled to turn to the minimum of instruments, that is to say, only two, in which I saw the possibility of solving the instrumental and acoustic problem.” This new work strives for “lyricism with rules in the spirit of the pastoral poets of antiquity and their scholarly art and technique.

Igor Stravinsky: Duo Concertante

The Duo Concertante, together with transcriptions of other Stravinsky works, formed the program for recitals that Stravinsky and Dushkin presented in Europe and the United States between 1932 and 1937. A critic writes, “Mr. Stravinsky had never played the piano so smoothly and clearly, with polish, almost with zest. Mr. Dushkin was efficient and authoritative. The ensemble was excellently adjusted.” Parts of the programs were taken up by transcriptions that produced a fresh look at a familiar repertoire but one that did not require many rehearsals and “would pave the way for more performances and more income.”

Samuel Dushkin and Igor Stravinsky

Stravinsky was clearly impressed by Dushkin’s transcriptions. As he wrote, “to know the technical possibilities of an instrument without being able to play it is one thing; to have that technique in one’s fingertips is quite another.” Stravinsky’s early violin transcriptions had been somewhat problematic, but his later efforts with Dushkin enabled the soloist to bring forth the composer’s ideas without sacrificing the effect. A scholar writes, “the philosophy of placing sonority first and ease of execution second inevitably creates some prickly passages amongst otherwise agreeable writing, but these passages are the most interesting aspects of the music.”

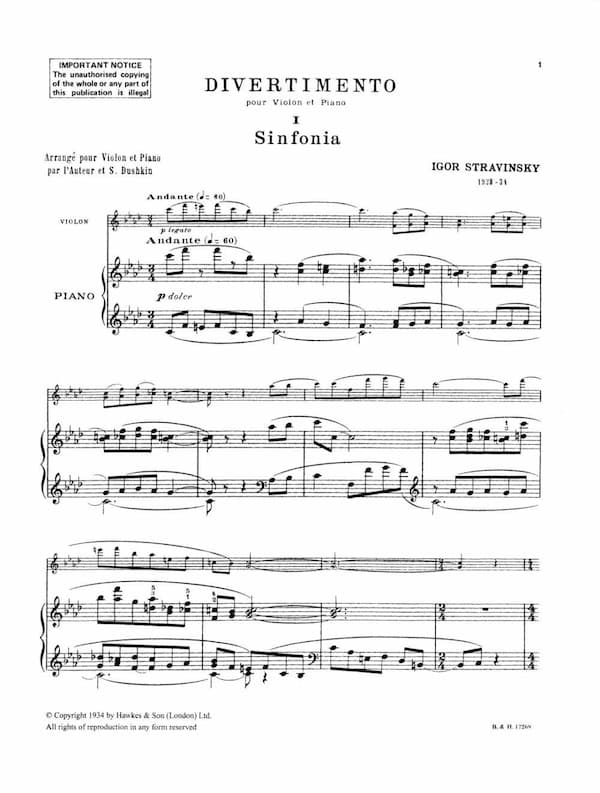

Igor Stravinsky: Le baiser de la fee: Divertimento (arr. S. Dushkin) (Liana Gourdjia, violin; Katia Skanavi, piano)

Dushkin and Stravinsky spent almost ten years in close contact, sometimes even daily. For Dushkin, the contact with Stravinsky represents the high point of his artistic career.

Never before or never since was he as successful as when he performed with Stravinsky as pianist or conductor. In Dushkin’s hands, these transcriptions become entirely idiomatic.

Stravinsky’s Divertimento, arranged by Samuel Dushkin

While Stravinsky listened carefully to Dushkin in technical matters, he refused to compromise on his aesthetic. The appeal of Dushkin’s playing for Stravinsky is perhaps seen in its evident intellect and demonstrative precision, especially rhythmically. To some commentators, “Dushkin demonstrated much of the mainstream approach of younger players of the 1920s and 1930s. Whilst not exceptional in themselves, his strong links with Stravinsky give the works composed within this collaboration a defining sense of authority. However, Dushkin not only collaborated with Stravinsky but also wrote a work for George Gershwin, concertos for William Schuman and Bohuslav Martinů, premiered the orchestral version of Ravel’s Tzigane, and composed a series of religious chants. All that and more is coming up in our next episode.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Igor Stavinsky: The Firebird, “Berceuse” (arr. S. Dushkin) (Isaac Stern, violin; Alexander Zakin, piano)