“Art begins where technique ends”

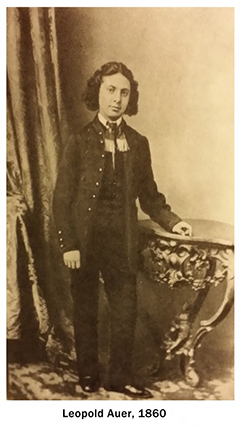

The Hungarian-born violinist, conductor and educator Leopold Auer (1845-1930) counted Jascha Heifetz, Nathan Milstein, Mischa Elman, Efrem Zimbalist, and numerous other great musicians as his students. In fact, he is rightfully referred to as the founder of the Russian violin school, and subsequently became a decisive force in the development of modern Hungarian violin pedagogy. Auer worked with Liszt, Brahms, Anton Rubinstein and the famous cellist Charles Davidov, and he founded and performed with his world-famous “Auer Quartet,” an ensemble that still performs to this day.

The Hungarian-born violinist, conductor and educator Leopold Auer (1845-1930) counted Jascha Heifetz, Nathan Milstein, Mischa Elman, Efrem Zimbalist, and numerous other great musicians as his students. In fact, he is rightfully referred to as the founder of the Russian violin school, and subsequently became a decisive force in the development of modern Hungarian violin pedagogy. Auer worked with Liszt, Brahms, Anton Rubinstein and the famous cellist Charles Davidov, and he founded and performed with his world-famous “Auer Quartet,” an ensemble that still performs to this day.

The Dispute Over Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto

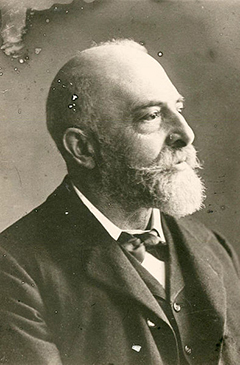

The String Quartet of the Saint Petersburg branch of the Russian Musical Society (RMS)

For many music lovers and concertgoers today, Auer’s name is connected with Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto. Tchaikovsky originally intended to dedicate his Violin Concerto of 1878 to Auer, but the violinist claimed, “although the work contains many beautiful musical thoughts, some of its parts are not idiomatic for the violin.” The press got ahold of the story, and as the result of this public humiliation, the composer withdrew the dedication to both the concert and the earlier Sérénade mélancolique. Auer eventually did play the concerto in 1893 after having made his alterations. It was in this edited Auer version that the Tchaikovsky concerto has been performed for much to the twentieth century.

Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35 (Pinchas Zukerman, violin; Israel Philharmonic Orchestra; Zubin Mehta, cond.)

Road to Success in Russia

Leopold Auer

Born in Veszprém on 7 June 1845, Auer started his studies at the age of eight at the Budapest Conservatory with Ridley Kohné. His performance of the Mendelssohn concerto secured a scholarship in Vienna, and Auer continued his studies at the Vienna Conservatory with Jakob Dont. By the age of 13 Auer had launched his professional career, but performances as far afield as Paris proved unsuccessful. As such, Auer sought the advice of Joseph Joachim. He would later describe his apprenticeship with Joachim in the following way. “Joachim was an inspiration for me and opened before my eyes horizons of that greater art of which until then I had lived in ignorance. With him I worked not only with my hands but with my head, studying the scores of the great masters and endeavoring to penetrate the very heart of their works…” After a highly successful appearance at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, Auer was engaged as the concertmaster in Düsseldorf, and subsequently held the same position in Hamburg. Visiting London in 1866, Auer was invited to perform with Anton Rubinstein and cellist Alfredo Piatti. On Rubinstein’s recommendation, Auer was appointed to succeed Wieniawski as violin professor at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1868 on a three-year contract. As it happens, Auer would stay in Russia for 49 years.

Auer: Schumann – Myrthen, Op. 25: No. 3. Der Nussbaum (Antal Szalai, violin; József Balog, piano)

Glorious Days in the Imperial Theatres and Conservatory

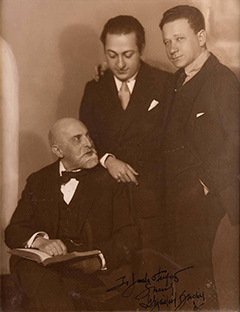

Auer with Heifetz and Zimbalist

For nearly half century, Auer was first violinist to the orchestra of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres. That included the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny—subsequently renamed Imperial Mariinsky Theatre—and the Imperial Theatres of Peterhof and the Hermitage. As court violinist he was required to perform all the violin solos in the performed ballets, most of them choreographed by Marius Petipa. Such was his fame and acceptance that the noted ballet composers of the day, including Pugni, Minkus, Drigo, Tchaikovsky, Arensky, Taneyev and Glazunov, wrote dedicated violin solos to showcase Auer’s talents.

Auer, Heifetz, Rachmaninoff, Hoffman

Auer also led the string quartet of the Russian Musical Society, and most of his pedagogical workmanship took place at the Conservatory. The majority of his students came to him as finished technicians, so that he could develop their interpretative powers. Auer’s enduring legacy was “virtuosity controlled by fine taste, classical purity without dryness, intensity without sentimentality.” The so-called “Russian” bow grip ascribed to Auer, consists of pressing the bow stick with the center joint of the index finger. This results in a richer tone, thought at the expense of flexibility.

Auer: Drigo – Arlekinada, “Harlequin’s Millions”: Serenade, “Notturno d’amore” (Antal Szalai, violin; József Balog, piano)

From Russia to USA

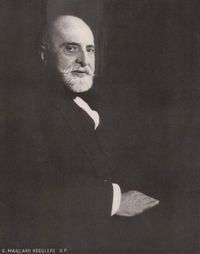

Leopold Auer

During his early days in Russia, Auer was compared unfavorably to Wieniawski. It was said that his “technique lacked a certain virtuoso flair, perhaps because of the poor physical structure of his hand.” However, his noble and fine-grained interpretations of the great concertos eventually convinced all his skeptics. During the summers between 1906 and 1911 Auer taught in London, and between 1912 and 1914 in Dresden. The Russian Revolution of 1917 forced Auer to depart Russia for Norway, and he sailed to New York in February 1918.

His former students welcomed him with open arms, and Auer played concerts in New York, Boston, Chicago and Philadelphia. He went on to teach in New York and at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. Auer wrote his memoires “My Long Life in Music” in 1923, and he became a US citizen in 1926. Auer died in Germany in 1930, and was interred in the Ferncliff Cemetery in Harsdale, New York. Jascha Heifetz once said, “Auer is a wonderful and an incomparable teacher; I do not believe there is one in the world who can possibly approach him… He is different with each pupil… and half an hour with Auer is always to me a great emotional and intellectual stimulus. He has a remarkable mind, a remarkable wit, a remarkable nervous system, and a remarkable magnetism.”

Auer: Arr. Rubinstein, Melodie in F Major, Op. 3, No. 1 (Antal Szalai, violin; József Balog, piano)

Good afternoon, I am looking for the Memories that Auer wrote. My father, Robert Kitain, was also his pupil in Skt. Petersburg.

How can I get them?

Thanks

Tamara Kitain

Hi Tamara,

You can search online but we have the feeling that the book is out of stock.

Good luck!