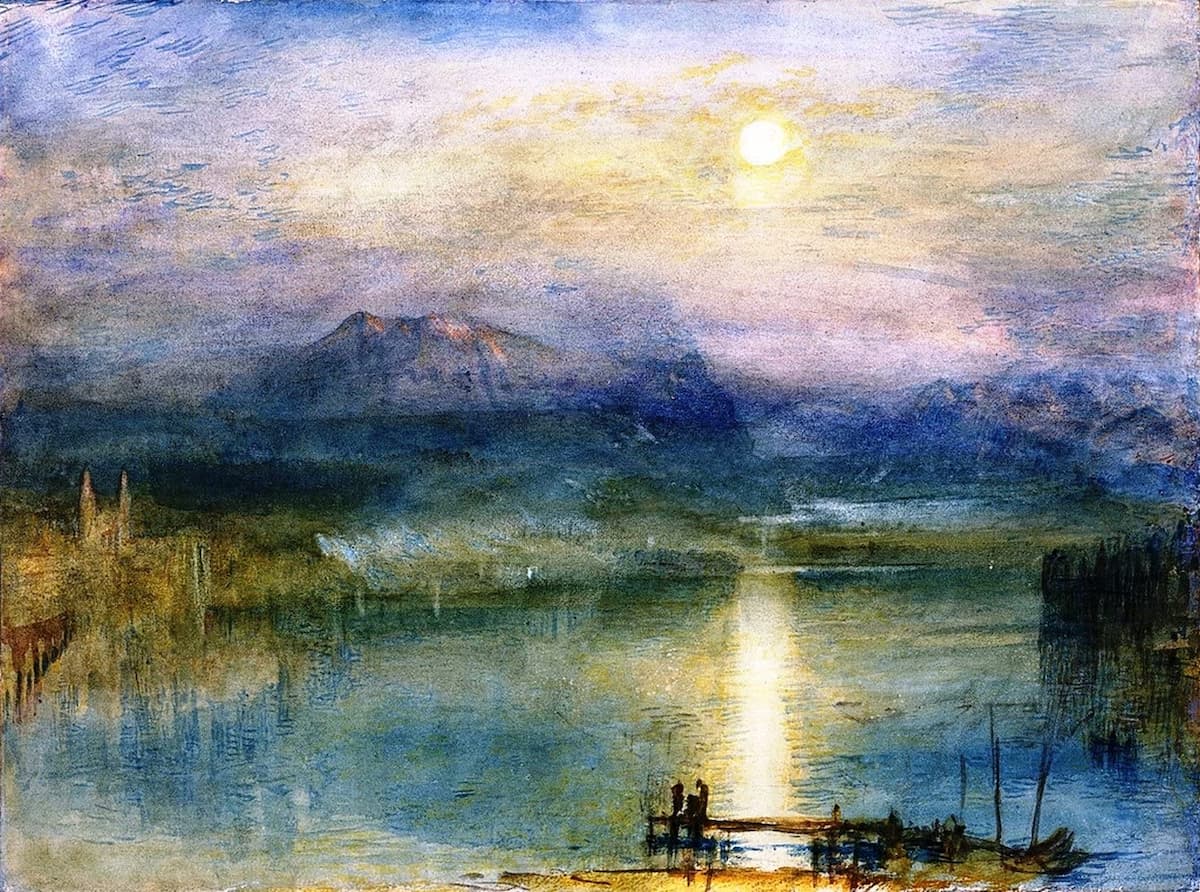

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 2 “Moonlight”

William Turner: Moonlight on Lake Lucerne

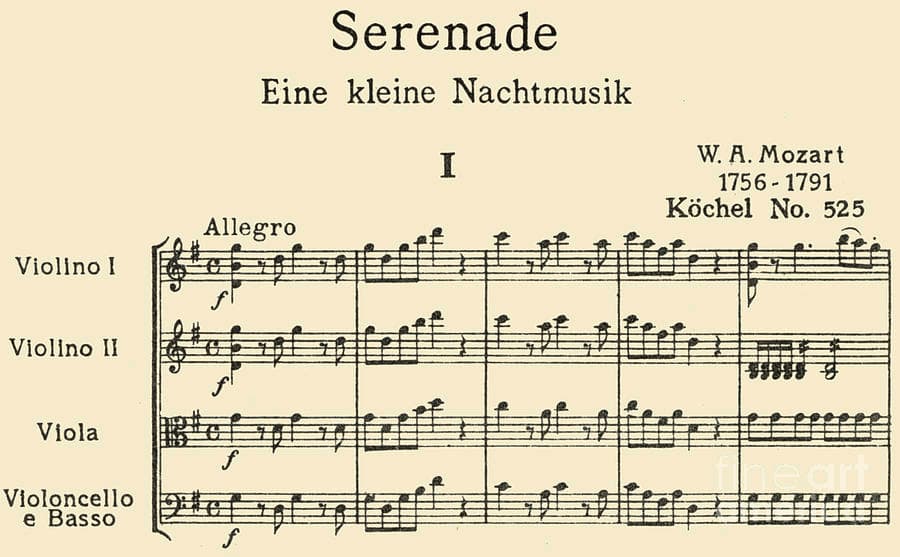

In the wonderful and whacky world of fancy nicknames, nothing is more famous than Beethoven’s “Moonlight” Sonata. Unsurprisingly, that particular nickname does not originate with Beethoven. In fact, it comes from remarks made by the German music critic and poet Ludwig Rellstab. Upon hearing the first movement of Beethoven’s C-sharp minor piano Sonata Op. 27, No. 2, Rellstab suggested that it inspired “a vision of a boat on Lake Lucerne by moonlight.” Beethoven, of course, had never been to Lake Lucerne, nor did he ever hear the appellation “Moonlight” Sonata, since it was not affixed until five years after his death. Beethoven had titled the work “Sonata quasi una fantasia,” at least that’s what the score of the first edition tells us. Regardless of name, this sonata was already hugely popular during Beethoven’s lifetime, a fact that somewhat puzzled the composer. “Surely” he exclaimed to a friend, “I’ve written better things!” The “Moonlight” nickname has stuck, and it has also been the subject of rather heated discussions. Some critics have called it “a misleading approach to a movement with almost the character of a funeral march.” Others find it evocative, in line with their own interpretations, or even harmless. One outspoken commentator wrote, “What this hysterical rage with poor Rellstab fails to grasp is that unless the general public had responded to the suggestion of moonlight in this music Rellstab’s remark would long ago have been forgotten.” As far as I can tell, this sonata was composed under the influence of Beethoven’s encroaching deafness, and a note written by Beethoven suggests that the first movement was inspired by Mozart’s murder scene in Don Giovanni. It makes rather a big difference in terms of interpretation whether one wants to emphasize “Moonlight” or “Murder,” don’t you think?

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55 “Eroica”

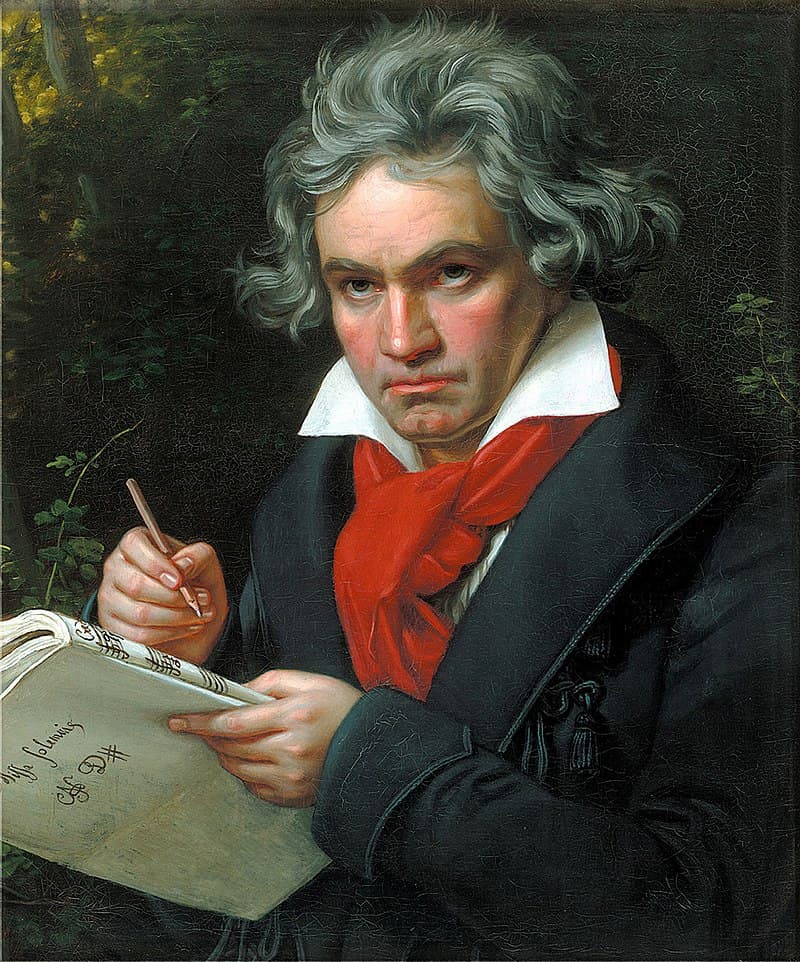

Joseph Karl Stieler: Beethoven, 1820

Beethoven might not have been too happy with the nickname “Moonlight,” but he did indeed title his Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Op. 55 “Eroica.” And fortunately, we have a pretty good idea of how this symphony got its nickname. Beethoven admired the ideals of the French Revolution, so he dedicated his third symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte. “Beethoven considered Napoleon Bonaparte to be the embodiment of the democratic and anti-monarchical ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.” But then he had second thoughts because a dedication to Napoleon would not get him a fee paid by his royal patron Prince Lobkowitz. Always practical but politically idealistic, Beethoven did title the work “Buonaparte,” until Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor on 14 May 1804. Beethoven’s secretary reported, “In writing this symphony, Beethoven had been thinking of Buonaparte, but Buonaparte while he was First Consul. At that time Beethoven had the highest esteem for him and compared him to the greatest consuls of Ancient Rome. Not only I, but many of Beethoven’s closer friends, saw this symphony on his table, beautifully copied in manuscript, with the word “Buonaparte” inscribed at the very top of the title page and “Ludwig van Beethoven” at the very bottom… I was the first to tell him the news that Buonaparte had declared himself Emperor, whereupon he broke into a rage and exclaimed, “So he is no more than a common mortal! Now, too, he will tread underfoot all the rights of Man, indulge only his ambition; now he will think himself superior to all men, become a tyrant!” Beethoven went to the table, seized the top of the title page, tore it in half, and threw it on the floor. The page had to be recopied, and it was only now that the symphony received the title “Sinfonia Eroica.” When it was first published in 1806, the score was titled “Heroic Symphony, Composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Trio No. 4 in B-flat Major, Op. 11 “Gassenhauer”

Joseph Weigl

In 1798, during a period when Beethoven was trying to make his living as a freelance composer in Vienna, he published the Piano Trio in B-flat major, Op. 11. That particular trio has become known under the nickname “Gassenhauer.” Since I had no idea what that actually means, I had to look it up. It turns out to be a very specific Viennese term identifying a short vernacular ditty, basically a simple popular tune that could be sung or whistled while walking down the lane. A good many of these popular tunes originated in comic operas, and Beethoven used one such tune as the theme for a set of variations in his Trio Op. 11. The tune “Pria ch’io l’impegno” (Before I go to work, I must have something to eat), originated in the comic opera L’amor marinaro by Joseph Weigl. It tells the story of a pirate captain who wants his son to marry a respectable girl, an opera singer masquerading as a countess and her conman boyfriend and a deaf conductor who is always hungry. As it happened, this tune became a runaway hit and was also used by Joseph von Eybler, Johann Nepomuk Hummel and Niccolò Paganini. For Beethoven, although he was not directly responsible for the nickname, it was mission accomplished. Everybody in town would recognize and whistle along with his “Gassenhauer Trio.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 11 in F minor, Op. 95 “Serioso”

Therese Malfatti, c. 1834

An eminent musicologist wrote, “The (Beethoven) F-minor Quartet is not a pretty piece, but it is terribly strong—and perhaps rather terrible… The piece stands aloof, preoccupied with its radical private war on every fiber of rhetoric and feeling that Beethoven knew or could invent. Everything unessential falls victim, leaving a residue of extreme concentration, in dangerously high tension.” That’s pretty serious stuff, and maybe you know that the Beethoven Op. 95 is the only string quartet to which Beethoven himself appended a nickname. He inscribed it with the words “Quartett Serioso.” That nickname apparently derives from the tempo marking to the third movement, “Allegro assai vivace ma serioso,” but in terms of musical characteristics, it seems to apply to the entire piece. But more than that, it seemed to have been a highly personal project as he wrote to a fellow musician, “the quartet is written for a small circle of connoisseurs and is never to be performed in public.” The work dates from 1810, and it was indeed written during a period when Beethoven was going through a rough patch in life. His health was deteriorating, and his deafness was worsening. Although he had gained a level of financial independence, his proposal to marry the 19-year-old Therese Malfatti had been rejected. As far as I can tell, the process of composition acted as a kind of emotional therapy for Beethoven, and although the quartet was completed in 1810, he only felt comfortable to release it four years later.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Sonata No. 26 in E flat Major, Op 81a, “Les adieux”

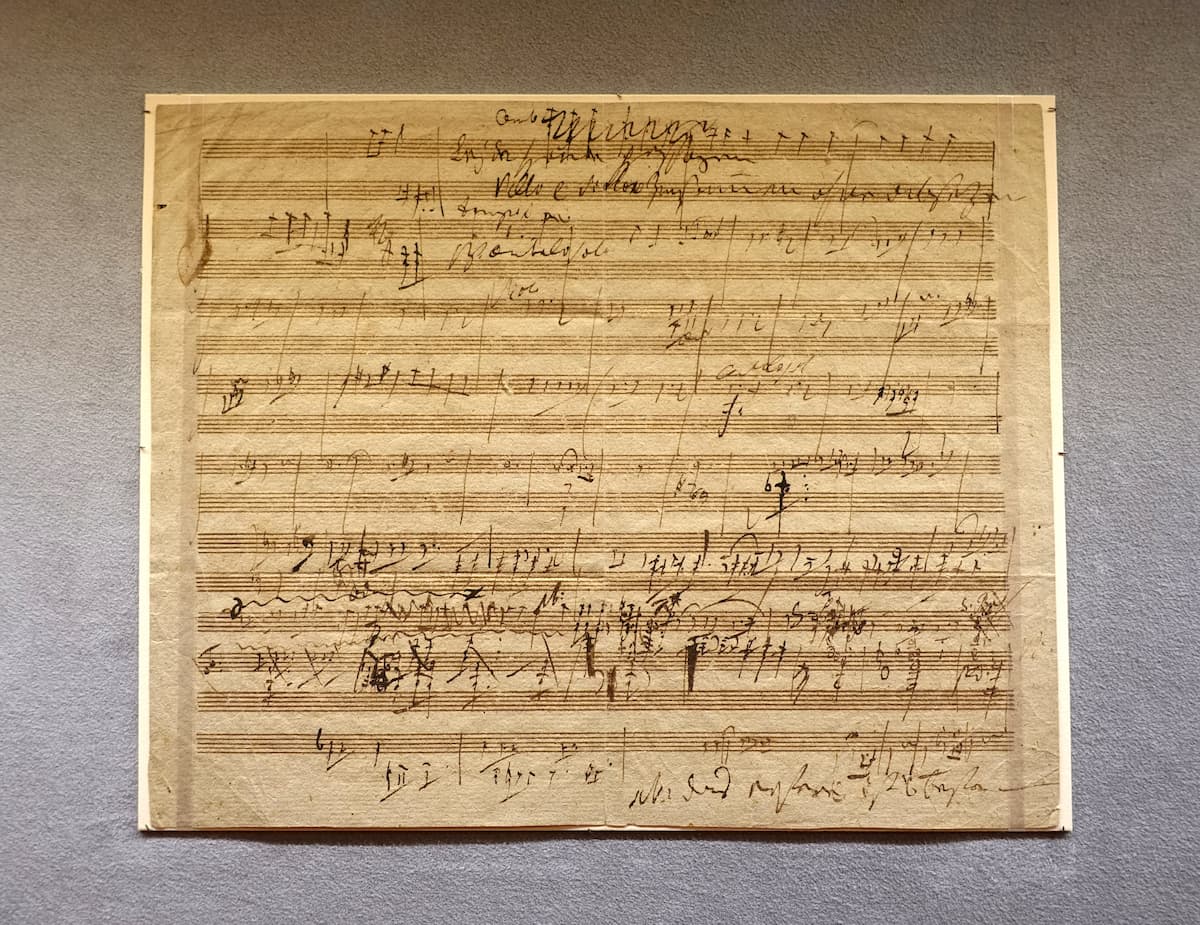

Sketches for the third and fourth movements of the Archduke Trio, Op. 97

The Piano Sonata No. 26 in E-flat Major, Op. 81a carries the title “Les Adieux” (Farewell). It’s not really a nickname, but “Beethoven’s deliberate programmatic attempt to musically encapsulate his feeling about the absence, and the eventual return of the Archduke Rudolph nine months later.” Archduke Rudolph was one of Beethoven’s most important patrons, and when Napoleonic troops lay siege to the city of Vienna, he did what aristocracy often does; he fled the city. Although the city was mounting a lengthy defense, the ruling nobility packed their suitcases and left. Rudolph, it turns out, wasn’t particularly worried about the rising inflation, hunger and disease that ravaged the local population. Beethoven did remain in Vienna, but he was complaining that the “booming cannons were causing his eardrums a great deal of pain.” Each movement of this sonata has a distinct title, commencing with “Das Lebewohl” (The Goodbye). A brief “Adagio” prefaces the opening movement and introduces a three-note horn motive over which Beethoven writes the three syllables “Le-be-wohl.” Expressing his sense of loss, loneliness, and consolation, Beethoven entitled the second movement “Abwesenheit” (The Absence). Finally, the music rushes through a series of deceptive cadences into the concluding “Das Wiedersehen” (The Return) movement. It’s easy to see why this work is commonly known as the “Farewell Sonata.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Trio in B-flat Major, Op. 97 “Archduke”

Archduke Rudolph

Talking about the Archduke Rudolph. He was a noble Habsburg by birth and showed an exceptional talent for music. He probably met Beethoven in the winter of 1803/04 and soon became his piano and theory student. Under Beethoven’s guidance, Rudolph improved steadily as a pianist and he premiered the violin sonata Op. 96 of his teacher. A critical observer wrote, “the performance as a whole was good, but we must mention that the piano part was played far better, more in accordance with the spirit of the piece, and with more feeling than that of the violin.” The Archduke also holds the unique distinction of having been Beethoven’s only composition student. In two decades of study, Rudolph produced a sizable and well-crafted body of music for piano, chamber ensemble, and voice. Beethoven complained that these lessons interfered with his own composing schedule, but since the Archduke was one of his most important patrons, he was careful not to tell him directly. Beethoven dedicated 11 of his greatest compositions to Rudolph, including the famous “Archduke” Trio. Beethoven did not supply that particular nickname, but it was easily derived from the dedication. He did, however, perform in the premiere of the work. The composer Louis Spohr listened to a rehearsal of the work and wrote, “On account of his deafness there was scarcely anything left of the virtuosity of the artist which had formerly been so greatly admired. In forte passages, the poor deaf man pounded on the keys until the strings jangled, and in piano, he played so softly that whole groups of notes were omitted, so that the music was unintelligible unless one could look into the pianoforte part. I was deeply saddened at so hard a fate.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68 “Pastoral”

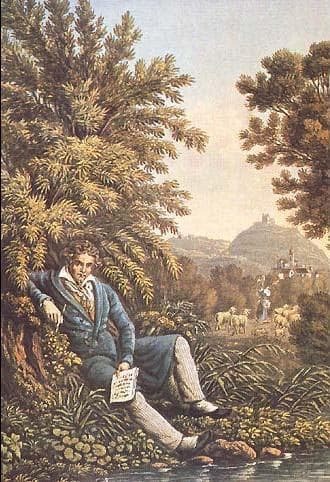

Franz Hegi: Beethoven composing the Pastoral Symphony

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 in F Major is one of only two symphonies Beethoven intentionally named. The full given title was “Pastoral Symphony, or Recollections of Country Life.” As my colleague has once written, “drawing upon the well-established genre of the programmatic symphony, the enormously popular “Pastoral” creates a musical universe where gentle repetitions and the imitation of nature define the structure on a small and large scale.” Beethoven just loved walking in nature, and he would write down musical ideas in a miniature sketchbook he always carried in his pocket. He described the “Pastoral Symphony” as more an “expression of feeling than painting.” And he made the descriptive movement titles public to the audience before the premiere.

The first movement is inscribed, “Awakening of cheerful feelings upon arriving in the country,” and the second movement “Scene by the brook” includes the famous bird calls. The last three movements flow into one another, and the third is titled “Merry gathering of peasants.” This happy meeting of a town band is interrupted by one of the most impressive thunderstorms ever to be sounded in music, “Tempest, storm.” Once the storm has passed, Beethoven sounds the “Shepherd’s hymn, happy and thankful feelings after the storm.” Every time I listen to this gorgeous “Pastoral Symphony,” I am in awe of how Beethoven managed to write a work that functions on both a descriptive and expressive level. I think we are on the verge of finding a new nickname for this symphony, as some present commentators have started to call it the “Environmental Symphony.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quintet in C Major, Op. 29 “Storm”

Ludwig van Beethoven

Nicknames find inspiration from a variety of sources. As we have seen with Beethoven, they might come from the composer, poets, critics, politicians, dedicatees, or popular songs. Nobody knows when and why the nickname “Storm” was appended to the String Quintet in C Major, Op 29. On one hand, it was composed during a time when the composer was struggling with increasing deafness. Beethoven was deeply depressed about his own social and emotional isolation, which he expressed in the suicide note of the “Heiligenstadt Testament.” There can be no doubt that an immense internal storm was raging in Beethoven’s mind. It is possible that Beethoven musically encoded that rage in the Finale movement of this Quintet. That movement does open with a violent tremolando storm in the lower parts, accompanied by flashes of lighting from the first violin. This opening “Storm” is contrasted by a childlike nursery tune before the storm returns with a vengeance. In this emotional rollercoaster, Beethoven then sounds an exaggerated courtly minuet leading once more to the return of the storm. It is certainly easy to hear why this movement might have given rise to the nickname “The Storm.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 5 in F Major, Op. 24 “Spring”

Beethoven’s Spring Sonata

Beethoven’s most popular violin sonata, his Sonata No. 5 in F major Op. 24 has earned its nickname “Spring,” on account of the vernal loveliness of the primary theme announced by the violin and echoed by the piano in the opening “Allegro.” Contemporary reviews called it “among the best Beethoven has written, which is to say that they are among the best being written at all. The composer’s original, fiery and bold spirit… becomes more and more apparent now…” To many listeners, this sonata feels like a warm breeze blowing through a window on an early spring day. The spontaneous lyricism and gentle radiance are not confined to the opening movement, however, with the entire sonata finding Beethoven in an especially buoyant state of mind. The nickname, as you might well imagine, did not originate with Beethoven but was added to this sonata after his death. The Beethoven manuscript does not show a title, but it does contain a Beethoven comment in red pencil. It reads, “The copyist who put triplets and septuplets here is an ass.” Just imagine what kind of nickname this sonata might have carried!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter