Classical Mozart vs. Romantic Beethoven?

When we read textbooks on music history, Mozart is frequently classified as a Classical, and Beethoven as a Romantic composer. It almost sounds like that these two musical giants were diametrically opposed to each other—like two boxers in a ring—with a clear boundary between them. Mozart and Beethoven didn’t hate each other, and they probably never personally met. Each clearly strove to express significant emotions, but they had somewhat different points of view. While the world of Mozart looked for order, poise, serenity and rational discourse, Beethoven’s world favoured ecstasy, wonderment, and irrationality. One searched for an objective and rational approach to life and art and looked upon the world in terms of universal brotherhood, while the other explored the world with intense subjectivity and in terms of personal feelings.

Apollo of the Belvedere

The philosopher Friedrich Nietsche compared the Classical era to Apollo, the god of light and measure, and the Romantic era to Dionysus, the god of wine, intoxication and passion. Both sentiments actually correspond to basic impulses of humanity, contrasting a need for moderation, entertainment, rationality and control of one’s emotion with the desire for uninhibited emotional expressions, the longing for the unknown and the unattainable. In simple terms, classicism is objective while romanticism is subjective.

Dionysus

As we know all too well from our present-day experiences, once rationality and feelings are treated as fundamental opposites, sparks do fly. Let us therefore survey notable composers active during the transitional period when aesthetic and musical worlds seemingly collided. Franz Schubert (1797-1828) might well be a central figure during this transitional period. Early in his career he was considered the last of the Classical composers, as he ignores the tumultuous Beethovenian models and returns to the poise and order of the Mozart universe.

Franz Schubert: Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat Major, D. 485 (Philharmonia Cassovia; Johannes Wildner, cond.)

The young Schubert by Josef Abel

This basic narrative of delineation between classicism and romanticism had social, cultural and economic roots and emerged from the revolutions in France and the United States. As an immediate outcome, power was transferred from the aristocracy to the middle class, and via the industrial revolution society depended on commerce and industry. It stimulated an emphasis on political, economic, religious and personal freedoms, but above all it featured an emphasis on the individual. And during the later stages of his career, Schubert decidedly turned towards the central ideas of romanticism. In his Lieder and late instrumental pieces he placed emphasis on the supernatural, the nocturnal, frightful and downright terrifying. Inspired by extra-musical associations, music became an entirely spiritual experience.

Hans Baldung, Death and the Maiden, 1517

For much of Mozart’s career, clarity, balance and transparency were hallmarks of the classical musical style. Music was subject to the principles of rhetoric and grammar, and contrasting musical ideas introduced listeners to opposing affects and ideas. A heavy

emphasis on musical form included intellectual and sometimes emotional dialogs, and the musical focus fell on melody and on a simple musical texture. Music was to be noble as well as entertaining, and it should always be natural and uncomplicated. Mozart, for subsequent generations seemingly became the poster child for this Classical musical style. However, when we really start to explore Mozart’s music, all these simplistic generalizations don’t hold true. While he was certainly guided by the ideals of classicism, the exceptional emotional and even demonic qualities that informed his finest masterpieces are definitely precursors of the romantic ideals. A scholar writes, “In all of Mozart’s supreme expressions of suffering and terror, there is something shockingly voluptuous.”

Portrait of Schubert by Gabor Melegh, 1827

We consider Ludwig van Beethoven a revolutionary composer working during revolutionary times. Imbued with the Romantic spirit, he loosened formal constraints and presented uninhibited expressions of his ideas and emotions. He found a new freedom of expressions, and in his instrumental music, freed from the burden of words, he could communicate pure emotion. His music does reach new extremes in terms of length and brevity, and he explored the most distant harmonic and tonal relationships. Extreme contrasts of dynamics are supported by the use of highly expressive terms as a hint to the mood of the music. Beethoven, it is argued, was preoccupied with inner problems, a sense of eternal longing, and a regret for lost happiness and childhood. Wrongly, we tend to think of Beethoven as a grumpy old pessimist. Nothing, however, could be further from the truth as he stands as a bridge between the Classical and the Romantic. In his compositions, Beethoven most perfectly struck a balance between these two contrasting worldviews.

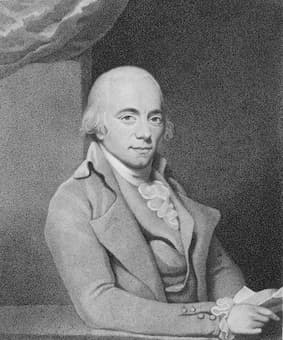

Muzio Clementi by Thomas Hardy

Mozart and Beethoven were not the only composers trying to make sense of this cultural paradigm shift. In fact, they were joined by a whole host of highly talented and exceptional composers. Among them was Muzio Clementi (1752-1832), remembered as one of the most noted and influential musicians during this transitional period. Born in Rome but mostly active in England, he was “the first of the great virtuosos and may well be regarded as the originator of the proper treatment of the modern pianoforte… he is the first composer completely equipped writer of sonatas.” Clementi personally met Haydn and Mozart, and he was aware of Beethoven’s late works. Beethoven had the highest regard for Clementi, and he greatly admired the Clementi sonatas because they were expressly written for the capabilities of the piano. Not unlike Mozart and Beethoven, Clementi stood firmly on the shoulders of both the classical and romantic traditions. And Johannes Brahms was one of his biggest fans.

Muzio Clementi: Keyboard Sonata in G Minor, Op. 34, No. 2 (Maria Clementi, piano)

Johann Nepomuk Hummel

Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) studied with Mozart for about two years between 1768 and 1788. Hummel’s talent impressed Mozart, and he not only agreed to teach him for free, but also provided him with free lodging and food. Hummel came to composition via the piano, just like Clementi, and he was also one of the great virtuosi of his day. Hummel’s own compositions obviously start with Mozartian models, but he took a different direction than Beethoven. Hummel simultaneously challenged classical harmonic structures and the extension of form, and his influence informed the early works of Chopin and Schumann. A critic writes, “the openings of the Hummel A minor and Chopin E minor concertos are too close to be coincidental.” Trying to make sense of the shifting parameters in musical thought, Hummel’s music powerfully reflects the transition from the Classical to the Romantic musical era.

Johann Nepomuk Hummel: Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Minor, Op. 85 (Martin Galling, piano; Stuttgart Philharmonic Orchestra; Alexander Paulmuller, cond.)

Franz Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1791

The Classical composer Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) had one of the most original musical minds. For long periods of time he was isolated from other composers and trends in music, and as he wrote, “It forced me to become original.” In a great number of compositions, Haydn loved to play with the expectations of the listeners. And in one particularly famous composition, his music is tied to a social cause, one of the distinct traits of musical romanticism. The “Farewell Symphony” is arguably Haydn’s most extraordinary composition. Haydn and his band of musicians were to remain for an additional two months in a remote location before being allowed to go home. Everybody protested, but Haydn’s solution was to compose a symphony with a message for Prince Nikolaus. At the end of the symphony, one by one, the players blew out the candles on their music racks and left the room. The Prince took the hint and Haydn won the day. Basing an entire five-movement symphony on extra-musical inspirations and social clauses is boldly knocking on the door of romanticism.

Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 45 in F-Sharp Minor, Hob.I:45, “Farewell” (Munich Chamber Orchestra; Alexander Liebreich, cond.)

The young Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) grew up in a household belonging to the intellectual and financial elite of Berlin society. By the time he had reached his 14th birthday, he already had an impressive variety and number of works in his compositional portfolio. In fact, between 1821 and 1823 alone, he composed a total of 12 symphonies for strings. The teenage composer assembled a series of compositions that skillfully synthesized Classical forms with Baroque techniques and Romantic orchestral techniques and symphonic processes. Mozartian in its formal clarity and expressive contrast, the development takes full advantage of this thematic simplicity by presenting the material in a variety of harmonic and instrumental guises. The harmonic progressions are highly sophisticated, and the fugal conclusion must have caused some mild surprises. Here as elsewhere in Mendelssohn, classical poise and romantic fervor happily coincided side by side.

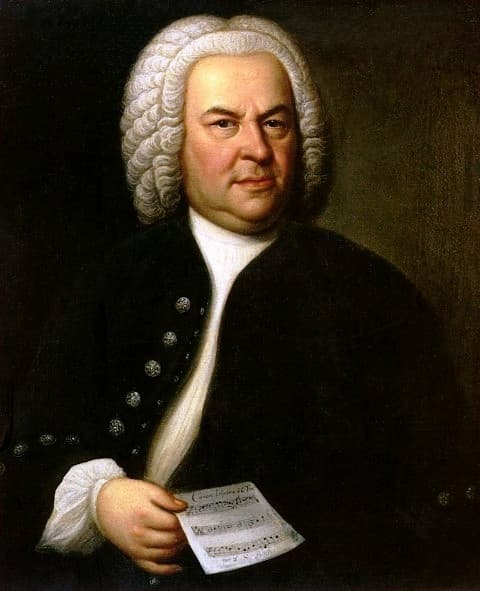

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

When we look for the precursors of musical romanticism, we clearly need to consider Bach. However, the Bach in question is Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788), son of the famed Johann Sebastian. He was highly esteemed during his lifetime and praised by Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven, but his name fell into neglect during the 19th century. Working in Berlin, C.P.E. maintained regular contacts with Moses Mendelssohn—grandfather of Felix Mendelssohn—the founder of German popular philosophy and one of the central figures of the Enlightenment. Concordantly, he was a close personal friend of the poet Johann Gellert. Gellert paved the way for a movement in German literature and art in which subjectivity and extremes of emotion were given free expression. Named “Sturm und Drang” (Storm and Urge) after a popular poem, this literary stream eventually relished tormented, gloomy, terrified and irrational feelings. Relying on extreme unpredictability and a wide range of emotions, C.P.E’s music easily moves with complete freedom and variety across the entire spectrum of structural designs. His true legacy is not merely felt in the psychological realm of Romanticism, but in the improvisatory and cyclic musical experiments of the19th century.

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: Sinfonia in E Minor, Wq. 178, H. 653 (Klaus Kirbach, harpsichord; Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Chamber Orchestra; Hartmut Haenchen, cond.)

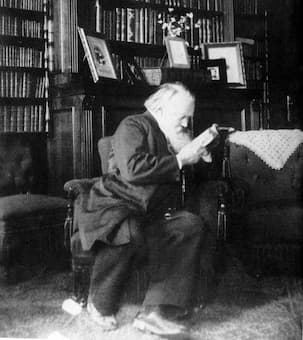

Johannes Brahms, c. 1894

In stark contrast to the stormy and passionate works of composers like Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) retained reverence for the classical heritage and maintained the Romantic tradition of his great predecessors. During his compositional career, Brahms exhibited a heightened sense of musical insecurity. He self-consciously responded to criticism, even when leveled by his closest personal friends, and he ruthlessly destroyed or severely reshaped his compositions. As a case in point, Brahms completed his B-major Trio in 1853 but revised the work some 36 years later. The revised work combines youthful romantic exuberance with sophisticated musical textures and an entirely logical and classical way of constructing motive and controlling their subsequent development. Brahms combines the warm lyricism of romantic imagination with a muscular intellectual rationality.

The title of this article talks about the collision of two musical worlds, but in reality it never happened. It is true that the composers featured in this article tried to artistically make sense of conflicting worldviews, but they still talked to each other and learned from each other. They drew inspiration from both sides of this aesthetic divide, and their artistic solutions and compromises are of fundamental significance to Western cultural and artistic thought.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Great article describing the differences and commonalities of classical and romantic music. Also, wonderful examples of performances.

What about Jan Ladislav Dussek? He was a Romantic sooner then musical traditionitalists want to admit. The level of Romantic expression in his music is just amazing.

The Schubert string quartet uses thirteenth chords. These contribute to the Romantic quality of the work. A typical one would be the minor 13th chord, spelled G, F, B, Eb.