Women loved Franz Liszt, and Franz Liszt loved women. The pianist and composer is almost as famous for his love life and his effect on women as his music-making.

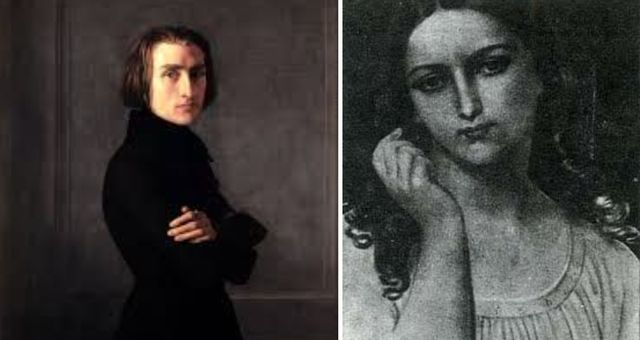

Henri Lehmann: Franz Liszt, 1840 (Paris Carnavalet Museum)

Today we’re looking at ten of the most intense love affairs that Franz Liszt ever had, from his long-term partners to short-term hookups to the stalker who made it her life goal to kill him.

Caroline de Saint-Criq (1828-1830)

Caroline de Saint-Criq

In the summer of 1827, when he was fifteen, Franz Liszt watched in despair as his father died. His father had also been his manager, and his death meant that Franz would have to make his way in the musical world alone.

That autumn, he began teaching piano to survive. One of his pupils was a kind, beautiful, wealthy seventeen-year-old girl named Countess Caroline de Saint-Criq.

By early 1828, the two teenagers had fallen in love. Franz taught her piano, while she taught him literature, introducing him to Dante, Victor Hugo, and other authors.

Caroline’s mother was sympathetic to their love and supported them, but tragically, she died in June 1828. After his wife’s death, Caroline’s father pressed his daughter to marry Bertrand Dartigaux, a wealthy family friend ten years Caroline’s senior.

Caroline married Dartigaux in March of 1831. Liszt took his first breakup hard and was depressed for months afterward.

Adele de Laprunarede, Duchesse de Fleury (1831)

Adele de Laprunarede

When he was nineteen, Liszt met a thirty-four-year-old married noblewoman named Adèle de Laprunarède at a Genevan hotel.

Supposedly she persuaded her older (and clearly oblivious) husband to invite Liszt to stay at their home, the Castle Marlioz in Savoy, France. Liszt accepted the invitation and came to visit in January 1831.

Legend has it that the roads to the castle became impassable with snow and ice, but that seems unlikely, as a letter to Franz’s mother survives from this time, meaning someone was able to get through to deliver it.

The affair fizzled out within a matter of weeks.

Franz Liszt: La Campanella (Evgeny Kissin)

Marie d’Agoult (1833-44)

Marie d’Agoult

Marie d’Agoult was born in 1805 in Frankfurt, the daughter of a French aristocrat and his German wife.

In 1827, when she was twenty-two, Marie married a man nearly twice her age and became the Comtesse d’Agoult. She didn’t love her husband and hinted in later writings that the physical side of their relationship was a disaster. Nevertheless, she had two daughters with him in 1828 and 1830.

In early 1833, she met Liszt at a gathering in Paris. Their relationship was initially platonic as they spoke to each other about their life experiences and shared interests. But when Marie moved (temporarily, as it turns out) out of Paris in 1833, they realized the true depth of their feelings for one another.

Tragedy struck in December 1834, when Marie’s six-year-old daughter died. Not long afterward, she and Liszt began sleeping together, and soon she found out she was pregnant with Liszt’s baby. Blandine-Rachel Liszt was born in December 1834.

In the end, Marie left her husband, causing a great scandal. She and Liszt eventually had three children together: Blandine in 1834, Cosima in 1837, and Daniel in 1839. The relationship with Liszt had freed her from the necessity of living a conventional bourgeois life, and she became an influential historian and author.

Unfortunately, however, that relationship started breaking down as early as 1837. Things were on and off for years, but they finally split for good by 1840. She drew on the fateful relationship when writing her novel Nélida.

Marie Pleyel (1840)

Marie Pleyel

Marie (nicknamed Camille) Moke was born in 1811 in Paris. She became a celebrated pianist by her teens.

Her career almost came to an end in 1831 when her fiancé – composer Hector Berlioz – came very close to killing her and her mother in a dramatic murder-suicide. Luckily, at the last moment Berlioz chose not to follow through.

The reason Berlioz had gotten so enraged was that she’d broken up with him long-distance and suddenly married a man named Camille Pleyel instead. It was an economically savvy match, as Pleyel was the heir to a piano manufacturer.

However, the young woman refused to be tamed. Even after her marriage she continued having love affairs, and in 1834 her humiliated husband asked for a divorce.

It is believed that Liszt and Marie hooked up around 1839 or 1840. There is evidence that Chopin once came back to his apartment after traveling and realized that Franz and Marie had had a tryst there in his absence. (He was horrified.)

It was never going to be a long-term arrangement due to their respective careers, but it seems like they had fun. Liszt wrote to her in the 1840s after dedicating a work to her: “Such is the sorcery of your person and your talent that if you would only not disdain to run through these few pages of Reminiscences with your inimitable fingers I have not the slightest doubt that they will present themselves as something new and will product the most magnificent effect.”

Franz Liszt: Réminiscences de Norma by Bellini (Goran Filipec)

Caroline Ungher (1822, 1839)

Caroline Ungher

We don’t have much evidence that this relationship ever happened, but Marie d’Agoult accused Liszt of romancing this famous contralto, so we’re including her on the list.

Caroline Ungher was born in Vienna in 1803 and studied voice with Mozart’s sister-in-law, debuting in a performance of Così fan tutte in 1821.

On 7 May 1824 she was an integral part of the premiere of Beethoven’s ninth symphony, singing the alto solo part.

In between those two performances, she once played at the same concert as Liszt.

Rossini described her as having “the ardour of the south, the energy of the north, brazen lungs, a silver voice and a golden talent.”

In 1835, she had a passionate love affair with writer Alexandre Dumas, author of The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. However, in 1841, she married author François Sabatier, who changed his name to François Sabatier-Ungher after their wedding in recognition of his wife’s career.

Marie d’Agoult suspected Liszt of being unfaithful in 1839 as their partnership unraveled, and she was especially suspicious of Ungher. We may never know exactly what – if anything – happened between them.

Lola Montez (1844)

Lola Montez

Eliza Rosanna Gilbert was born in Ireland in 1821. She eloped in 1837 as a teenager with an army lieutenant named Thomas James, but the marriage only lasted five years.

She came to London and took to the stage as a Spanish dancer, performing under the pseudonym Lola Montez. However, it wasn’t long before audiences recognized her, so she slipped away to continental Europe to allow the scandal to die down.

While there, she made her living as a courtesan. In 1844, she debuted in Paris to a decidedly cool reception, but she also had an affair with Franz Liszt and met his circle of friends, so the trip wasn’t entirely wasted.

In 1846, she became the mistress of King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Legend has it that he asked her if her breasts were real, and she responded by disrobing.

After Ludwig lost power, she escaped to America, went on tour in Australia, and, in 1861, died of syphilis.

Hamelin Plays Liszt – Un Sospiro

Marie Duplessis (1845)

Marie Duplessis

Marie Duplessis was born in 1824 to a poor family in Normandy. She endured a childhood rife with horrific abuse. In 1838, when she was just fourteen, her father sold her to an elderly man of seventy. Eventually she escaped him and found work as a shop girl.

Her charm and beauty were beguiling. She soon became a courtesan, spending time with wealthy and intellectual men in both public and private.

Between September 1844 and August 1845, she was the mistress of Alexandre Dumas’s son, who shared his name.

In 1845, she met Franz Liszt in the foyer of a Parisian theater. Critic Jules Janin later recalled their meeting:

Head held high, she made her way through the astonished throng, and we were surprised, Liszt and I, when she came and sat down familiarly on the bench beside us, for neither of us had ever spoken to her. She was a woman of wit and taste and good sense. She began by addressing herself to the great musician; she told him that she had recently heard him, and that he had made her dream…and so they talked throughout the third act of the melodrama…

Liszt may have been the great love of her life. He later wrote about what she’d told him one night, despairing over her poor health:

“I shall not live; I’m a strange woman, I shan’t be able to cling to this life that I cannot live and I cannot bear. Take me with you, take me away wherever you want; I shan’t be in your way, I sleep all day, in the evening you’ll let me go to the theater, and at night you can do what you like with me!”

Tragically, she died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty-three in 1847. Alexandre Dumas’s son immortalized her in an 1848 novel called La Dame aux Camélias, which a few years later became the inspiration for Verdi’s opera La Traviata.

Carolyn Sayn-Wittgenstein (1847-1865)

Carolyn Sayn-Wittgenstein

After Marie d’Agoult, Liszt’s next long-term relationship was with Carolyn Sayn-Wittgenstein.

She was born in 1819 in present-day Ukraine to nobility. In 1836, when she was still a teenager, she was forced to marry Prince Nicholas von Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg-Ludwigsburg, a twenty-four-year-old aristocrat who became the governor of Kiev.

Predictably, the marriage was unhappy. The couple only had one daughter, and they separated after a few years.

In 1844, she inherited a fortune from her father, granting her a measure of independence, and in 1847, she met Liszt and saw him perform in Kiev for the first time.

She and Liszt fell in love and moved together to Weimar. She fought for years to have her first marriage ruled invalid so that she could marry Liszt. It broke her heart that she was never successful, although she came agonizingly close. Her relationship with Liszt turned platonic after their planned wedding fell through.

She was instrumental in convincing Liszt to perform less and focus on composition: a move that helped to cement his legacy in music history.

She was also astonishingly productive creatively herself. Between 1868 and 1887, she published forty-four volumes of prose.

Valentina Lisitsa Plays Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2

Agnes Street-Klindworth (1854-1857)

Franz Liszt and Agnes Street-Klindworth © radiofrance.fr

Agnes Klindworth was born in 1825 in Bremen, Germany. She was a talented pianist and began studying under Liszt in Weimar in 1853, when she was twenty-eight and Liszt forty-two.

She had a secret: she was the illegitimate daughter of journalist and diplomat (some might say spy) Georg Klindworth, and she was in Weimar gathering intelligence about French and Russian interests. Liszt had friends in both camps, so it made sense to get to know him.

Between 1855 and 1861 the two kept up a voluminous correspondence. They also became lovers while Liszt was still (ostensibly) with Carolyn Sayn-Wittgenstein, who never knew the details about his hookups with Agnes.

Liszt fell very deeply in love with her and wrote letters describing his yearning for her (that he instructed her to burn, which she never did). We don’t know exactly how deep her love for him went, but she did travel great distances to have trysts with him.

Even after they stopped sleeping together, they stayed friends until Liszt’s death.

Olga Janina (1869-1871)

Olga Janina

Olga Zielinsky was born around 1845 in present-day Lviv, Ukraine. She got married, took her husband’s last name of Janina, divorced him, and then set out to become a piano virtuoso.

She came to study with Liszt in Rome in 1868. She was an unusual student from the start: she dressed like a man, loved talking about controversial ideas like free love and atheism, and bit her nails so badly that she’d bleed on the keyboard. She also was a heavy drug user and was suicidal.

We’re not clear whether she and Liszt actually slept together, but they were close. However, Liszt soon became alarmed by her mental health issues, and their friendship, such as it was, deteriorated.

At the end of an American tour in 1871, she sent him a cable and told him she was going to kill him. She wasn’t lying: she showed up at Liszt’s door with a revolver and some poison for herself (that was later revealed to not be poison at all).

After Liszt’s camp threatened to get the police involved, she changed tactics, trying her best to destroy his reputation instead.

She wrote four thinly veiled books of fiction about an extremely steamy love affair between a female narrator and an unnamed great pianist (wink, wink).

In one of her books, the pianist is attracted to her but insists that “he cannot love” because of his position in the church. (Liszt was an abbé at this time.) So the narrator decides he must either love her or she must kill him. Luckily he chooses her, and they sleep together.

Janina sent her books to Liszt’s friends…and the Pope.

Did the two really go to bed together? We don’t know for sure. But regardless of the answer, Janina was one of the most striking women Liszt was ever linked to, in a life full of striking women!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

My God! He was active! I I knew about Marie d’Agoult but not of the others, and I never suspected he had had a relationship with Traviata self.

Feminists of today should be reminded that they have illustrious forerunners (and they ran fast!) in the XIXth century.

I love Interlude articles, they are witty and very well written. I learn a lot.

Yeah I once knew a woman like this last one “Janina”, this one who looks like a young man ,

She was mean and had very bad tempers .. The first time I humped her I smelled a very nasty smell .. suicidal woman usually have stinking smell .. Every time I tried to get rid of her she threatened me that she was going to burn the cars or the apartment or herself ! etc.. and keeps stalking me until I let her in again

There is nothing more scary than a hopeless deranged woman ..