Marie Duplessis

Marie Duplessis (1824-1847) was one of the most famous and sought-after French courtesans of her time. Born on 15 January 1824, her father wasn’t a particularly pleasant man, and early on sold his daughter to a variety of men. It is said that Marie lost her virginity at the age of 12, and by age 16 she decided on a career as a courtesan in Paris. She soon became the mistress of a steady stream of incredibly wealthy French aristocrats, and between September 1844 and August 1845 she was the mistress of the legendary French writer Alexandre Dumas (1824-1895).

Giuseppe Verdi: La Traviata title page

He remembered her as “tall, very slim with long, black, lustrous hair, Japanese eyes, very quick and alert, with lips as red as cherries and the most beautiful teeth in the world.” And the literary critic Jules Janin remembered “her young and supple waist, the beautiful oval of her face and the grace which radiated like an indescribable fragrance.” Sadly, by the time Marie first met Franz Liszt, she was already seriously ill with consumption, the polite term for tuberculosis, and she died in 1847.

Verdi: La Traviata, Act 2 duet

Alphonse Mucha: The Lady

of the Camellias

Alexandre Dumas first published his semi-autobiographical novel La Dame aux Camélias (The Lady with the Camellias) in 1848. Based on his brief love affair with Marie Duplessis, the novel tells the love story between Marguerite Gautier, a demimondaine or courtesan suffering from consumption, and Armand Duval, a young bourgeois. The title of the novel derives from Marguerite “wearing a red camellia when she is menstruating and unavailable for sex and a white camellia when she is available to her lovers.”

Francesco Maria Piave

Armand falls in love with her and he convinces her to leave the life of a courtesan and live with him in the country. Armand’s father Germont is horrified by the scandal caused by the illicit relationship and convinces Marguerite to leave. Armand believes that she has left him for another man, and her death is described as “abandoned by everyone and suffering an unending agony.” In the novel, Marguerite, despite her past, “is rendered virtuous by her love for Armand, and the suffering of the two lovers, whose love is shattered by the need to conform to the morals of the times.”

Verdi: La Traviata, Act I “Sempre Libera”

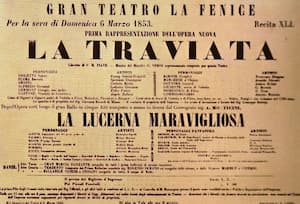

Verdi’s La Traviata premiere poster

Giuseppe Verdi and Giuseppina Strepponi visited Paris in 1851/52, and they attended a performance of Dumas’ La Dame aux Camélias. Verdi had previously agreed to write a new opera for the 1853 Carnival season at the Teatro la Fenice in Venice with Francesco Maria Piave as the librettist. In October 1852 Verdi complained that Piave “had not yet offered him any original or provocative ideas,” but once he returned home from Paris, both quickly set to work on an adaptation of Dumas’ play.

Felice Varesi

The working title of the opera, later changed at the insistence of the Venetian censors, was “Amore e morte” (Love and Death). Verdi was convinced that it would be “called La traviata (The Fallen Woman). A subject of our own age.” Just a couple of months before the agreed upon première Verdi was still focused on his unfinished Trovatore. The Venetian theater management sent a stern reminder to Verdi and Piave, and the librettist wrote, “Everything will turn out fine, and we’ll have a new masterpiece from this true wizard of modern harmonies.” In the event, La traviata was composed in record time.

Verdi: La traviata, Act I “Un di felice, eterea”

Fanny Salvini-Donatelli

Verdi proposed that the opera should be performed in modern costume but the Venetian authorities demanded a historical setting playing at the beginning of the 18th century. The première cast included Fanny Salvini-Donatelli as Violetta, Lodovico Graziani as Alfredo and Felice Varesi, creator of Rigoletto and Macbeth, as Giorgio Germont. The opera premiered on 6 March 1853 at La Fenice opera house in Venice. Scholars write, “that performance was the most celebrated fiasco of Verdi’s late career.”

Lodovico Graziani

The audience was particularly incensed by the casting of Salvini-Donatelli in the lead role of Violetta. She was an acclaimed singer, but “considered too old at age 38 and too overweight to credibly play a young woman dying of consumption.” In addition, Varesi was too far past his prime to tackle the exposed role of Germont, and the audience turned against the performance. As Verdi famously wrote to a friend the next day, “La traviata last night a failure. Was the fault mine or the singers? Time will tell.” We do know that Verdi was reluctant to allow further performances, and after making various alterations to the score the opera soon became one of the composer’s most popular works, “and it has retained this position into modern times.” Famous for its moments of lyrical introspection, it is Verdi’s most realistic drama with the “cultural ambience of the subject matter and the musical expression very closely related.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Verdi: La Traviata, Act III “Parigi, o cara”