Wilhelm Müller

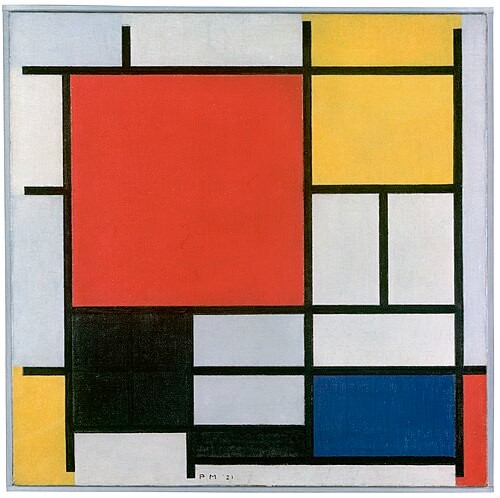

Wilhelm Müller’s poetic imagination is rooted in a strong sense of proportion, in what has been termed his “architectural sense.” However, none of his poems can be forced into the mold of a rigid system. “Everything develops organically between such polarities as spirit/matter, inward/outward, and light/darkness.” Concurrently, his poems abound with musical sensitivity, and the heart is transformed into a prism through which the light “of the spirit may shine.”

Vineta Island

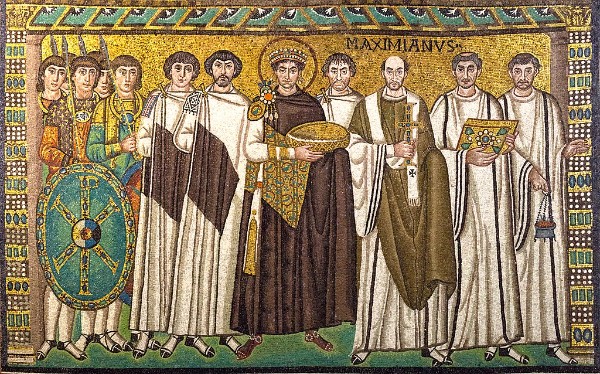

In 1860, Johannes Brahms wrote to Clara Schumann, “the Lied is sailing so far off course these days that one can’t overemphasize the need for an ideal.” For Brahms and other artists, the traditional forms of country life were being relentlessly overwhelmed by industrialization. As such, they searched and cherished an ideal of simplicity, purity and beauty, which they hoped to mirror in their art. The inherit dangers of violating this harmony and balance was described in Müller’s poem “Vineta.” The title refers to a mythical city off the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, when inhabitants were punished for their excessive way of living by a devastating flood.

Johannes Brahms: 3 Gesänge, Op. 42, No. 2 “Vineta” (Monteverdi Choir; John Eliot Gardiner, cond.)

Vineta, 1693

Aus des Meeres tiefem, tiefem Grunde | From the ocean’s fathomless depths |

klingen Abendglocken, dumpf und matt. | sound evening bells, dull and faint, |

Uns zu geben wunderbare Kunde | to bring us wondrous tidings |

von der schönen, alten Wunderstadt. | of the lovely ancient magic city. |

|

|

In der Fluten Schoß hinabgesunken, | Deeply sunken in the bosom of the waves, |

blieben unten ihre Trümmer stehn. | its ruins remained down below. |

Ihre Zinnen lassen goldne Funken | Its pinnacles show golden shimmers |

widerscheinend auf dem Spiegel sehn. | reflected in the mirror of the sea. |

|

|

Und der Schiffer, der den Zauberschimmer | And the fisherman, once he has seen |

einmal sah im hellen Abendrot, | the magic shimmer in the evening glow, |

nach der selben Stelle schifft er immer, | always returns to the same place, |

ob auch ringsumher die Klippe droht. | although the cliffs around him threaten. |

|

|

Aus des Herzens tiefem, tiefem Grunde | From the heart’s fathomless depths |

klingt es mir wie Glocken, dumpf und matt. | I hear the sound of bells, dull and faint. |

Ach, sie geben wunderbare Kunde | Ah, they give wondrous tidings |

von der Liebe, die geliebt es hat. | of the love that once it loved. |

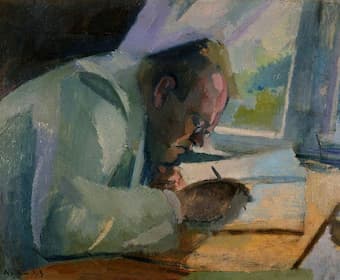

Urs Joseph Flury

The Swiss composer Urs Joseph Flury, working in a new romantic impressionist tradition, encoded his impressions of this ancient myth in a symphonic poem aptly titled “Vineta.”

Urs Joseph Flury: Vineta (Bieler Symphony Orchestra; Urs Joseph Flury, cond.)

Giacomo Meyerbeer

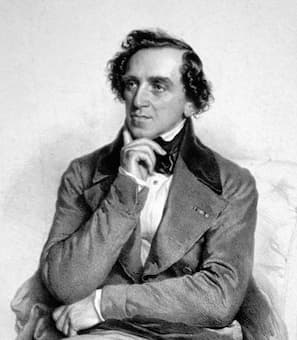

The lieder by Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) are currently not part of the standard song repertoire. Meyerbeer hailed from Berlin, and he spent a number of years in Italy in order to learn how to compose vocal music. A good many of his songs were composed for performances in the salons of the Paris bourgeoisie, and generally speaking, the French mélodie stood at the center of his song composition. However, Meyerbeer also set texts by Heine, Goethe and Müller. Instead of taking his baring from the tradition of the German Lied, Meyerbeer sought new avenues of expression by finding inspiration in the successes of his grand operatic production. And such is certainly the case in his 1839 setting of Müller’s poem “Meeresstille.”

Giacomo Meyerbeer: “Meeresstille” (Ning Liang, mezzo-soprano; Ilmo Ranta, piano)

Felix Draeseke

Felix Draeseke (1835-1913) had exceptional musical talents, composing his first work at age nine. Eventually, he added eight operas, four symphonies, various dramatic works and highly original vocal and chamber music compositions to his musical oeuvre. In addition, he published numerous reviews, biographies, books on music history and theory and a treatise on the philosophy of music. Felix entered the Leipzig Conservatory in 1852 and devoted the next three years to the study of music. However, he became dissatisfied with the conservative brand of historicism practiced at the Leipzig Conservatory—established by Mendelssohn and eagerly followed by Brahms—and found his musical calling in the music of Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner. He was described as “an especially dangerous beast among the members of the New German School,” and Hans von Bülow remarked, “he is a tough nut to crack, and despite the quality of his works, he will never be popular among the ordinary.” In his “Buch des Frohmuts” (Book of Joy) Op. 17, Draeske included a fascinating setting of Müller’s poem “Abendreihn.”

Felix Draeseke: Buch des Frohmuts, Op. 17, “Abendreihn” (Ingeborg Danz, alto; Cord Garben, piano)

Guten Abend, lieber Mondenschein! | Good evening, lovely moonlight, |

Wie blickst mir so traulich ins Herz hinein! | How intimately you gaze into my heart; |

Nun sprich, und laß dich nicht lange fragen, | Now speak and ask no more questions, |

Du hast mir gewiß einen Gruß zu sagen, | You must surely have a greeting to give, |

Einen Gruß von meinem Schatz! | A greeting from my sweetheart! |

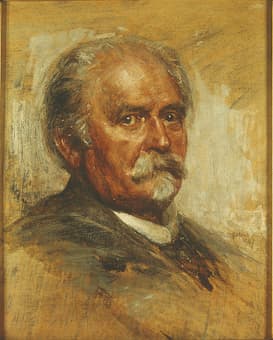

Max Reger, 1913

The very same poem served as inspiration for a choral setting by Max Reger (1873-1916). Although Reger brusquely suggested, “the male voice chorus did not particularly appeal to him,” he nevertheless created a substantial repertoire for men’s choir. His distinct musical language is characterized by rich and darkly colored sounds that seemingly conflicts with traditional male choral compositions. And once you add fluctuating harmonies that quickly change to distant keys, the old Müller poem appears in an entirely modern musical guise. Müller’s interest in folk poetry played an important part in the developing of a German folk style. His poetry was set many times by lesser composers, and the musicality of his verses encouraged readings that found a permanent home away from the refined world of the art song. Müller was only thirty-three when he died of a stroke.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Max Reger: 7 Male Choruses, Op. 38, No. 6 “Abendreihn” (Ensemble Vocapella Limburg; Tristan Meister, cond.)