Wilhelm Müller

On 15 December 1822, Wilhelm Müller wrote a letter to the composer Bernhard Klein. Klein had set a number of poems from “Die schöne Müllerin,” and Müller thanked him for “the musical animation of my verses.” Müller writes, “My songs lead but half a life, a paper life of black and white… until music breathes life into them, or at least calls it forth and awakens it if it is already dormant in them.” Müller openly invited collaborations with musicians, and his exceptionally personable nature assured that he enjoyed an extended circle of friends. Müller was officially employed as the Imperial Librarian at Dessau in Prussia, and “he was a tireless contributor to a number of almanacs and yearbooks, both as a poet and a critic.”

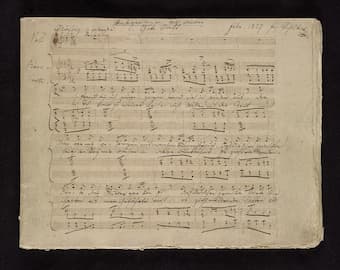

Schubert: Winterreise “Gute Nacht”

In 1822, Müller had edited a ten-volume set of German poetry, and in 1821 and 1824, he issued two volumes of an anthology of 77 poems. Supposedly, the poems originated from the posthumous papers of a travelling horn-player, and the “Die schöne Müllerin” appears in the first, while “Die Winterreise” was published in the second volume. The 1823 edition of the almanac “Urania” contained the first twelve poems of Müller’s “Die Winterreise,” and Schubert set these initial 12 poems to music in February 1827.

Franz Schubert: Winterreise, Op. 89, D. 911 (Hermann Prey, baritone; Helmut Deutsch, piano)

Fremd bin ich eingezogen, | As a stranger I arrived, |

Fremd zieh’ ich wieder aus. | As a stranger I departed. |

Der Mai war mir gewogen | May was kind to me |

Mit manchem Blumenstrauß. | with many bouquets of flowers |

Das Mädchen sprach von Liebe, | The girl spoke of love, |

Die Mutter gar von Eh’, – | her mother even of marriage. |

Nun ist die Welt so trübe, | Now the world is dismal, |

Der Weg gehüllt in Schnee. | the path is covered in snow. |

Leopold Godowsky

The poem immediately presents an image of utter alienation, portrayed in terms of real human emotions. These psychological states are viewed in existential terms, as the man is not only rejected by the girl but by the world as well. Instead of a dramatic curve the “Winterreise” presents a succession of psychological states encompassing the whole gamut of emotions. In his piano transcription, Leopold Godowsky draws attention to that fact by skillfully varying each strophe of the original songs.

Leopold Godowsky: Gute Nacht (Konstantin Scherbakov, piano)

Hans Zender

Roughly 170 years after Schubert’s setting, the German composer Hans Zender (1936-2019) composed a re-interpretation of Schubert’s “Winterreise.” Although Zender is considered one of Germany’s most distinguished post-war composers, his music has made little impact outside his native country. His setting differs from the Schubert original in that it uses an orchestra of strings, guitar, harp, various percussion and wind instruments. However, the essential difference lies in the fact that the musicians “wander” through the room during the concert. They only stop to play their parts, and then move on again. “Wandering,” that essential part of Müller’s poem and of Schubert’s setting becomes a physical reality. The sound structure builds up slowly as more and more musicians, “walk in a very calm, almost ritual movement,” through the auditorium and onto the stage. As such, the restlessness of the Schubert setting of the poem stands at the very center of this wandering activity.

Hans Zender: Schubert – Winterreise – No. 1. Gute Nacht (Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; Ensemble Modern; Hans Zender, cond.)

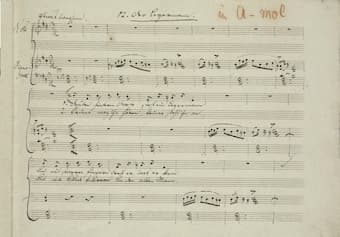

Schubert: Winterreise Der Lindenbaum

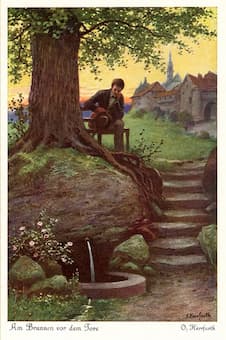

A good many of Müller’s poems have established themselves as popular folksongs. “Der Lindenbaum,” from Winterreise is one of the most beloved folksongs in the German-speaking world. “It has established itself in the consciousness of the populace to such an extent that the author’s identity is often forgotten.” As such, the poem, without giving credit to a particular authorship, supposedly expresses the “soul of a nation.” Characteristic of many German villages, the linden tree is not only the focal point of these settlements, but also a place to find peace of mind. It also becomes the focal point of the wanderer’s longing. Müller’s spatial arrangement of the scenery “is thus an exact correlative for the relationship between the two states of consciousness—the everyday world of waking life and the world of dreams.”

Am Brunnen vor dem Tore, | By the well at the town gate |

da steht ein Lindenbaum: | there stands a linden tree |

Ich träumt in seinem Schatten | In its shadow I have dreamed |

so manchen süßen Traum. | many sweet dreams. |

|

|

Ich schnitt in seine Rinde | In its bark I carve |

so manches liebe Wort; | many a loving word; |

es zog in Freud’ und Leide | in joy and in sorrow it drew |

zu ihm mich immer fort. | me back again and again. |

Franz Schubert: Winterreise, Op. 89, D. 911 – No. 5. Der Lindenbaum (Mitsuko Shirai, soprano; Hartmut Höll, piano)

Die kalten Winde bliesen | The icy wind blew |

mir grad ins Angesicht; | straight into my face; |

der Hut flog mir vom Kopfe, | my hat flew off my head. |

ich wendete mich nicht. | I did not turn back. |

|

|

Nun bin ich manche Stunde | By now I am many hours |

entfernt von jenem Ort, | away from that place; |

und immer hör’ ich’s rauschen: | but I still hear the rustling: |

Du fändest Ruhe dort! | There you would find peace! |

Schubert: Winterreise Der Lindenbaum

While the first two stanzas present the sphere of the tree, the third stanza describes the wanderer’s recent encounter with the tree. He tries to remain unaffected by the mysterious force of the tree blocking his field of vision. In the final stanza the temporal progression has finally reached the present, with the ultimate rest found only in the realm of eternity. For a good many commentator, “The Lindenbaum” is the “actual heart of the Winterreise cycle.”

Matthias E. Becker: Am Brunnen vor dem Tore (Cologne Kantorei; Volker Hempfling, cond.)

Am Brunnen vor dem Tore – Oscar Herrfurth

Wilhelm Müller joined the Prussian army in 1813, and he was stationed in Brussels during the Wars of Liberation. Apparently, he had an affair with a married local woman; behavior frowned upon since he was a member of the occupying powers. He was dismissed from the army and traveled on foot from Brussels to Berlin in the middle of winter. As such, his personal “Winterreise” might actually have left deep autobiographical traces in his poetic cycle. To some commentators, it prophetically also resonates with today’s age, “dominated by feelings of uncertainty in a world of material orientation and social iciness.” And that sense of isolation is beautifully captured in “Loneliness,” the final poem of the first part. Like a sad and lonely cloud he wanders through the bright and happy life around him. “Even when the storms were raging, I was not so miserable.”

Franz Schubert: Winterreise, Op. 89, D. 911 – No. 12. Einsamkeit (Pavol Breslik, tenor; Amir Katz, piano)

Ida Henriette da Fonseca

Ida Henriette da Fonseca (1802-1858) was an accomplished singer and she gave her debut on 8 December 1827 in the title role as the crusader in Rossini’s Tancredi. Born in Copenhagen, she embarked on grand tours through Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden and was named “one of the greatest singers in Scandinavia.” In fact, the correspondent of the “Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung” called her the best female singer in Copenhagen. She was named royal court singer in 1841, and after her retirement worked as a singing teacher. In addition, she became one of the first Danish woman composers, issuing her first work in 1848. She did offer 18 songs through subscription, meaning that the composer is prepaid by a number of subscribers before actually issuing a work. Fonseca published a second volume in 1853, which included, among others, 8 solo songs with piano accompaniment. Her setting of “Einsamkeit” is a mixture of Nordic ballad, German lied and an Italianate operatic style.

Ida Henriette da Fonseca: Einsamkeit (Helene Hvass Hansen, soprano; Cathrine Penderup, piano)

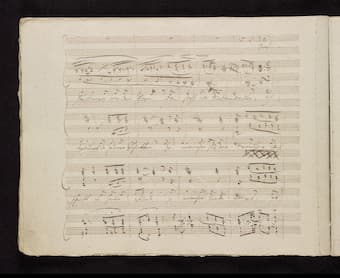

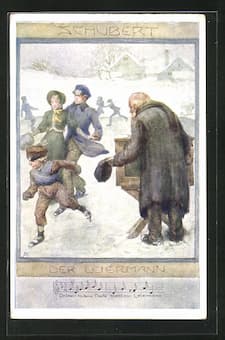

Schubert: Der Leiermann

Having set the first 12 songs of “Winterreise,” Schubert subsequently discovered the full series of poems in Müller’s book of 1824. Schubert therefore discovered that between the 1823 and 1824 editions, Müller had varied some texts and adjusted the order of the poems. “Schubert’s original group of settings therefore closed with the dramatic cadence of “Irrlicht,” “Rast,” “Frühlingstraum,” and Einsamkeit,” and his second sequence begins with “Die Post.” Dramatically, the first half is the sequence from the leaving of the beloved’s house, and the second half the torments of reawakening hope and the path to resignation.” Müller concludes his cycle with one of his most powerful poems. “Der Leiermann” presents a disturbing picture of the utter alienation of man. Here, the themes of isolation introduced earlier in the cycle reach their climax. As the barefoot man is standing on the ice, even music, often considered a link with the divine, has become monotonous, automated and indifferent.

Drüben hinter’m Dorfe | Beyond the village borders |

Steht ein Leiermann, | stands a hurdy-gurdy man; |

Und mit starren Fingern | with his numb fingers |

Dreht er was er kann. | he plays as good as he can |

|

|

Barfuss auf dem Eise | Standing barefoot on the ice |

Schwankt er hin und her; | he teeters back and forth |

Und sein kleiner Teller | and his little plate |

Bleibt ihm immer leer. | remains forever empty. |

Franz Schubert: Winterreise, Op. 89, D. 911: No. 24. Der Leiermann (Christoph Prégardien, tenor; Tilman Hoppstock, guitar)

Wilhelm Kienzl

A contemporary critic wrote, “Müller is naive, sentimental, and sets against outward nature a parallel of some passionate soul-state which takes its color and significance from the former. Schubert’s music is as naive as the poet’s expressions; the emotions contained in the poems are as deeply reflected in his own feelings, and these are so brought out in sound that no-one can sing or hear them without being touched to the heart.” The melancholic aura surrounding Schubert’s setting creates a sense of ultimate desolation. In the setting by Wilhelm Kienzl (1857-1941), however, the effect becomes more purely lyrical. Although published in 1888, Kienzl’s setting dates back to a draft penned in 1872. As such, it is one of his earliest Lied settings, with the open fifths in the bass and the circling accompanying figures clearly taking their initial barring from Schubert. Müller never met Schubert nor did he ever see or hear his musical settings. Undoubtedly, however, he would have been delighted by some of the “Müllerin” settings and slightly bewildered by the “Winterreise.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wilhelm Kienzl: 2 Lieder, Op. 38: No. 1. Der Leiermann (Carsten Suss, tenor; Stacey Bartsch, piano)

thank you for the wonderful explications of the poems.

Mueller makes my heart sing.