“I may not be a first-rate composer, but I AM a first-class second-rate composer!”

Richard Strauss conducting

Born on 11 June 1864 in Munich, Germany, Richard Strauss (1864-1949) almost exclusively expressed his life and thoughts through music and the arts. From his glorious summation of 19th-century Romanticism to the deeply probing psychological experimentations of 20th-century Modernism, his long career spanned one of the most chaotic political, social, and cultural periods in human history. To celebrate his birthday, let’s explore the magnificent compositions of one of the most versatile, talented and creative forces in the history of music and culture.

Richard Strauss: Rosenkavalier Suite

Juvenilia

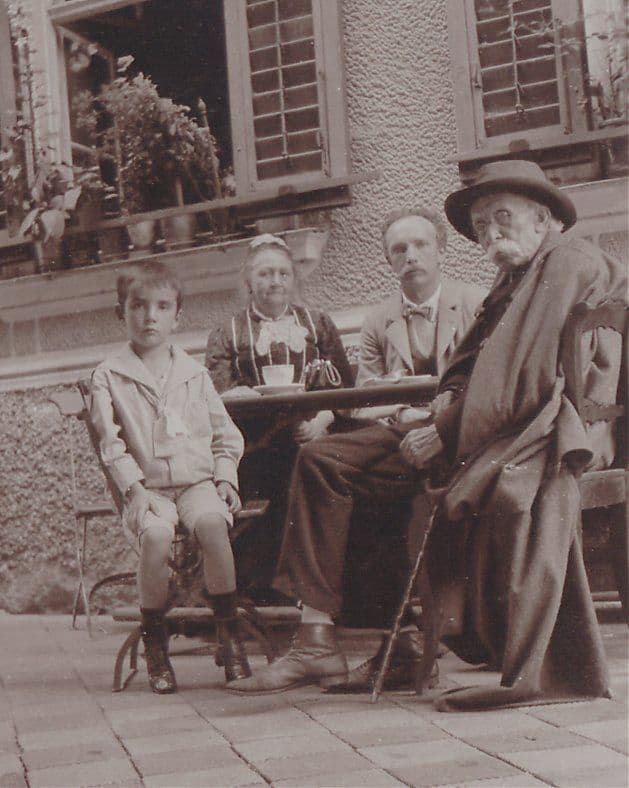

Richard Strauss and parents

Richard’s father Franz Strauss, a member of the Royal Court Orchestra in Munich and a celebrated horn virtuoso, quickly recognized the exceptional musical talents of his son. He started piano lessons at four and a half and made swift progress. Richard was also eager to try his hands at composition, and at the tender age of six, he composed a little polka for solo piano. He took up the violin under Benno Walter at age 8 and began five years of compositional study with Friedrich Wilhelm Meyer at age 11.

Young Richard was primarily interested in orchestral music, and his early instrumental works include marches, concert overtures and ultimately two symphonies. His Serenade for 13 Winds, Op. 7, composed when he was 17, led conductor Hans von Bülow to famously proclaim, “Richard Strauss is by far the most striking personality since Brahms.” Within this early phase of Richard Strauss’s career, we also find a number of works featuring solo instruments. The Violin Concerto Op. 8 was written for his teacher Benno Walter, and the Horn Concerto Op. 11 for his father.

Richard Strauss: Horn Concerto No. 1, Op. 11

Burleske

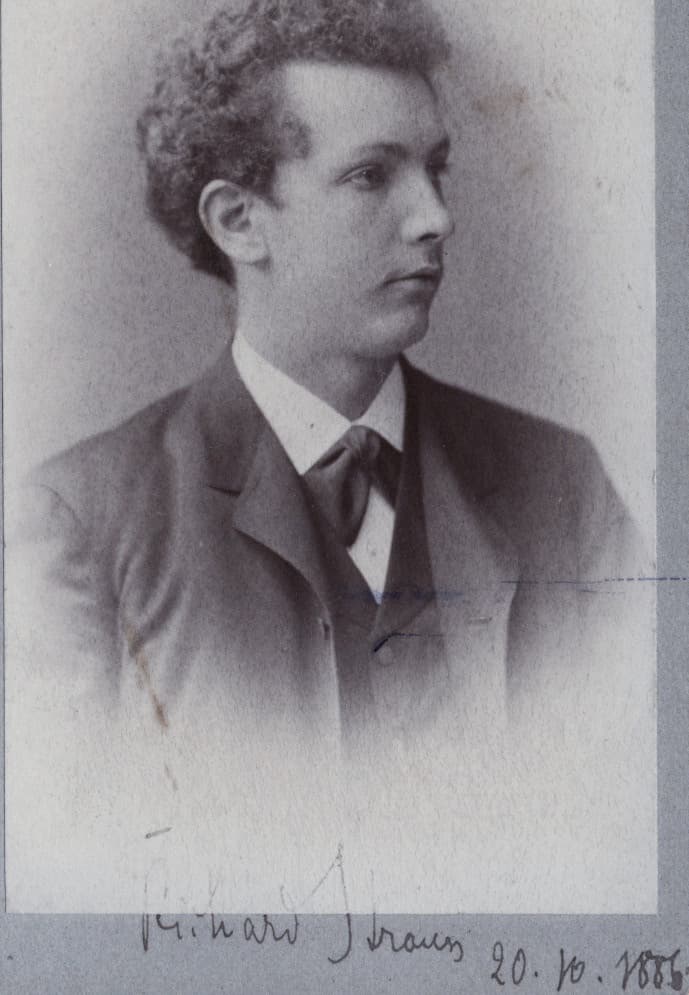

Richard Strauss at 22 years old, 1886

The Burleske, first performed in 1886, was dedicated to Bülow and “is one of the earliest pieces to use the historical canon as a source of parody, simultaneously burlesquing both piano concertos by Brahms and Tristan and Die Walküre by Wagner.” Strauss’s artistic sensibilities were developing with great rapidity, and he confessed to “feeling trapped in a steadily escalating antithesis between poetic content and formal structure.”

After spending several weeks touring Italy, Strauss sketched his tonal impressions to be used for his “first hesitant steps” into the realm of the tone poem. After the completion of Aus Italien in 1886, he jubilantly wrote to Bülow, “I am now capable of composing works based on external inspirations. New ideas must seek new forms.” Frequently described as a first step towards independence, Aus Italien gave rise to a series of magnificent works that represent a significant body of music of central importance in the late German Romantic repertoire.

Richard Strauss: Burleske in D minor

The Tone Poems

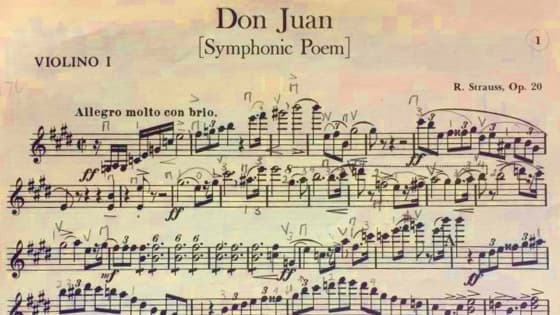

Richard Strauss’ Don Juan

Richard Strauss’s monumental tone poems, essentially written during a ten-year period from 1888 to 1898, fused the sheer force of Strauss’ imagination with his embrace of an aesthetic of program music that denounced traditional, abstract musical form as obsolete. In fact, Strauss crafted the central musical expressions of the Austro-German tradition at the turn of the century. These highly innovative orchestral works—ranging from Macbeth of 1888 to the Sinfonia domestica of 1903—with Eine Alpensinfonie added in 1915—project youthful confidence and virility in its music handling, but also in subject matters.

Don Juan (1889), with its provocative subject matter, dazzling orchestration, sharply etched themes, novel structure and taut pacing, earned Strauss his international reputation as a symphonic composer. Cosima Wagner, who was an early admirer of Richard Strauss, was deeply offended by the blatantly erotic subject matter. Although Wagner and Liszt had initially inspired Strauss to embrace the extra-musical, the young composer was determinedly and irreverently carving his own musical path.

Richard Strauss: Don Juan, Op. 20

Ein Heldenleben

Throughout his life, Strauss had been attracted by the philosophies of Friedrich Nietzsche, and he was especially partial to the notion that the “individual had the power to change the world around him, and was able to control his destiny without promise of a hereafter.”

For Strauss, the genius of Nietzsche found its greatest manifestation in his book Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Mirroring the nature and character of this literary source, Strauss musically depicts humanity not in search of eternity, but rather struggling to transcend religious superstition.

With his three last and largest tone poems, particularly with Ein Heldenleben (1899), Strauss faced mounting criticism, charges of excess, megalomania, superficiality, and bad taste. A Hero’s Life should not be read as a musical autobiography, however, as the music is much more psychologically complex than its showy and grandiose surface at first suggests. It is principally concerned with exploring the inner world of personality, emotion, and psychology; all deeply embedded in lush layers of irony and parody.

Richard Strauss: Ein Heldenleben, Op. 40

The Operatic Stage

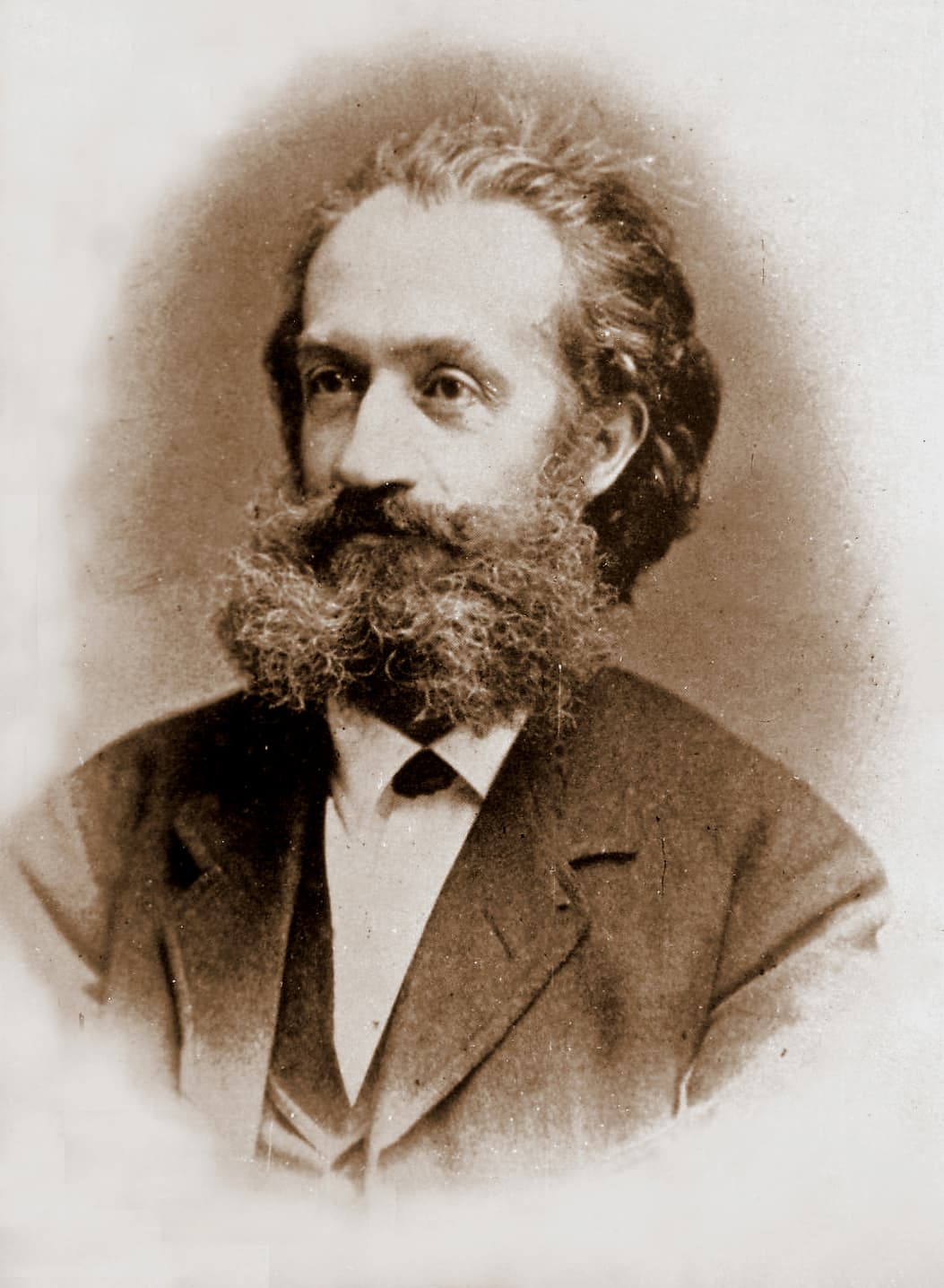

Alexander Ritter

Young Richard Strauss had grown up under the archconservative direction of his father Franz, who never missed an opportunity to rail against Richard Wagner’s music. When Richard Strauss took up his appointment with the Meiningen orchestra, he met the Estonian-born Alexander Ritter, who had married the niece of Richard Wagner. Ritter took an immediate liking to the young Richard, and began to engage him on the aesthetic beliefs of Liszt and Wagner, both of whom he regarded almost as gods. In his memoirs, Strauss credited Ritter with his so-called “conversion” to Wagner and the music of the future.

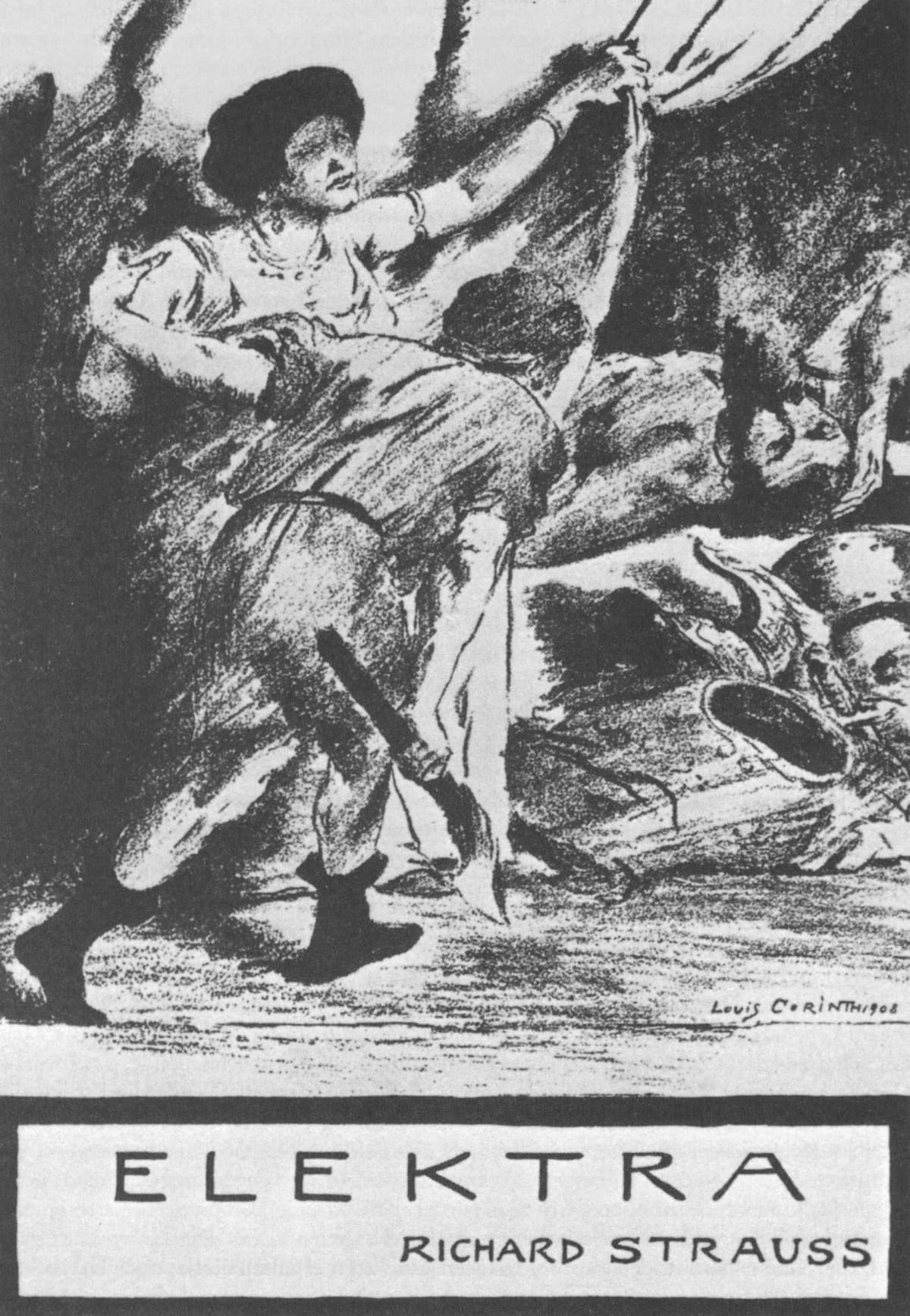

Ritter provided Strauss with an aesthetic focus for his creative energies, and above all, spurred the young composer to devote himself to the musical theatre. After the dismal failure of his first opera Guntram (1894) and the scandal caused by the sexual and erotic subtext of Feuersnot (1901), Strauss’s next opera, Salome (1905) simultaneously provoked fascination and revulsion. “Lust, incest, decapitation, and necrophilia is wrapped in a lush tapestry of dazzling orchestration,” and decidedly established Strauss as the leading German opera composer of his time. Elektra (1909), in turn, proved crucial to Strauss’s later development as a composer of opera, since it marked the beginning of his collaboration with the young Viennese poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

Richard Strauss: Elektra, “Finale”

Der Rosenkavalier

Richard Strauss’ Elektra, title page of the libretto, 1909

In terms of popularity, nothing comes close to Der Rosenkavalier (1911). Collaborating once more with Hofmannsthal, Strauss turned to 18th-century Vienna and the musical world of Mozart. This comic opera presents a critical layering of musical styles, referencing Mozart, Verdi, and the waltzes. It evokes a sense of sentimentality and denotes the middle-class sensibilities of Johann Strauss. Strauss essentially discloses his modernist preoccupation with the dilemma of history, and the popularity of the score has overshadowed the theatrical brilliance and modernity of the work.

Strauss further exploits the musical canon as a source of parody in Ariadne auf Naxos (1916), while Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919) is a complex mixture of operatic and musical elements. Based on a fairytale, the complexity of the libretto inspired Strauss to compose one of his densest scores, packed with intricate leitmotifs and brilliant orchestral colours. The comedy Intermezzo (1924), on the other hand, was inspired by Strauss’s wife mistakenly accusing him of philandering, while Die Ägyptische Helena (1928) returns to the more elevated world of Greek myth. Although Strauss referred to Die Liebe der Danae (1944) as his last opera, his final completed work for the stage was a “Conversation Piece for Music,” entitled Capriccio (1942). Rich in historical allusions and self-references, it represents the culmination of the composer’s work in this genre.

Richard Strauss: Der Rosenkavalier, “Presentation of the Rose”

Vocal Musings

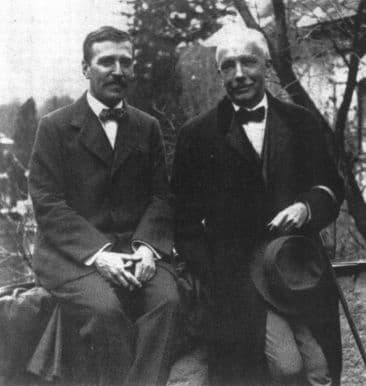

Richard Strauss with Hugo von Hofmannsthal

Richard Strauss composed Lieder throughout his entire life. In more than 200 songs, the composer thoroughly explored the German Romantic tradition and significantly advanced the genre with his autumnal orchestral songs. A good many songs were written for his wife, the celebrated soprano Pauline de Ahna, and Strauss went on to orchestrate some of them. Without doubt, the Vier letzte Lieder, which “contemplate the meaning of death, are among Strauss’s finest works in any genre.”

Strauss summed up his artistic legacy by stating, “I may not be a first-rate composer, but I AM a first-class second-rate composer!” This deceptively light-hearted self-assessment brings into focus the composer’s role in the growing rift between the 19th century bourgeois and a rapidly encroaching modernist perspective. For a good many scholars, Strauss and Schoenberg were the two greatest composers of the century, with the ideal likeness of Strauss not corresponding to a painting, drawing, or sculpture, “but to a mosaic, coherent from afar, but upon closer view made of numerous contrasting fragments.”

Richard Strauss died quietly in his sleep on 8 September 1949, and he was buried in the garden of his Villa in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Congrats on a fabulous bio sketch for the magnificent Richard Strauss. Fabulous “illustrations”

Salome is dynamite. Der Rosenkavalier was boring for me. And I am a deep Mozartian.