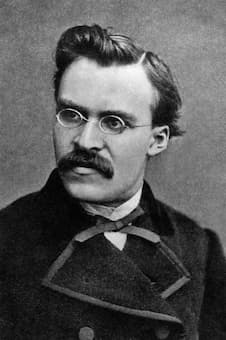

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

“God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?” This most widely quoted statement originating with Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche first appeared in the 1882 publication Die fröhliche Wisssenschaft (The jolly science) and is restated in Also sprach Zarathustra (Thus spoke Zarathustra).

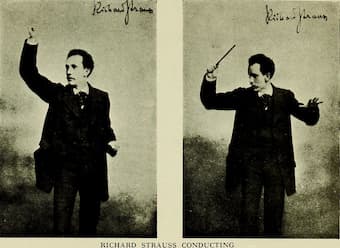

Richard Strauss, 1894

Naturally, this statement questioning the value and objectivity of truth—essentially looking at God as a historical process—spawned a number of philosophical and theological movements. But Nietzsche, who also wrote numerous texts on morality, contemporary culture, philosophy and science, never really trusted the written word. “In comparison to music,” he wrote, “all communication through words is shameless. The word diminishes and makes stupid; the word depersonalizes, the word makes what is uncommon common.”

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 – Einleitung (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 – Von den Hinterweltlern (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

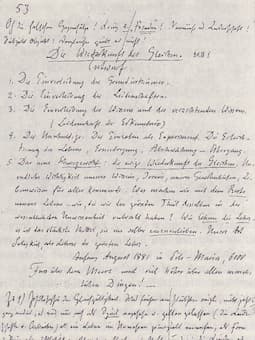

Note by Nietzsche about the

“Ewige Wiederkunft”

Strauss’ fascination with Nietzsche stemmed from his desire to discredit a prevailing metaphysical philosophy that saw music as a transcendental phenomenon. “Music,” he concluded, “could be nothing more than music.” Strauss himself introduced his tone poem “freely based on Friedrich Nietzsche,” in his program note for the 27 November 1896 premiere. “I did not intend to write philosophical music or to portray in music Nietzsche’s great work. I wished to convey by means of music an idea of the development of the human race from its origin, through the various phases of its development, religious and scientific, up to Nietzsche’s idea of the superman.”

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 – Von der grossen Sehnsucht (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 – Von den Freuden-und Leidenschaften (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

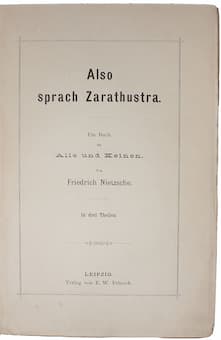

Also sprach Zarathustra

Zarathustra, is also known as “Zoroaster,” an ancient Persian prophet who preached monotheism in a predominantly polytheistic environment. For Nietzsche, Zarathustra becomes a mouthpiece to express his own ideas about the purpose of human life and the fate of humankind. According to Nietzsche, Zarathustra took himself to the mountains, staying there for ten years in solitude. Then, one morning, he arose and addressed the Sun, seeking his blessing. Eventually he proposes to descend once more among men to impart to them his wisdom, pouring out to mankind his accumulated understanding. Since Strauss’ symphonic poem depicts humanity not in search for eternity, but rather struggling to transcend religious superstitions, we may most reasonably hear this work as a lyric drama, captivating its listeners through vivid gestures and powerful characterizations.

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 – Das Grablied (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 – Von der Wissenschaft (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

Edvard Munch: Friedrich Nietzsche, 1906

Thus Spoke Zarathustra unfolds in nine sections, with the famous sunrise solemnly proclaimed by four trumpets against a slowly vibrating background of the organ and the low instruments of the orchestra. Providing a sense of infinite space, this opening theme sets in motion the two tonal centers that form the basis of the entire musical design. C major and C minor symbolizes Nature and the Universe, and B major and B minor represent the keys of Humanity. Each of the remaining eight sections of the continuous score is introduced by chapter titles taken from Nietzsche, ranging from Of the Backworldsmen through Of the Great Longing, Of Joys and Passions, Grave-Song, Of Science, The Convalescent, and The Dance-Song. The concluding Night Wanderer’s Song gradually recedes into a deafening silence, and the famous polytonal close—once again juxtaposing C and B major—mirrors the questioning and unsettling nature of Nietzsche’s own conclusion.

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 – Der Genesende (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 – Das Tanzlied (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

Richard Strauss, c. 1900

Strauss employed massive instrumental forces during the premiere on 27 November 1896. There can be no doubt that this work forever solidified Strauss’s reputation and revealed the essence of his singular orchestral language. Unfortunately, “Nietzsche neither heard nor was he aware of the composition,” as he suffered a total mental collapse roughly two years later. Thus Spoke Zarathustra has found an enthusiastic following in the 20th century, in large part inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Strauss’ opening is used highly effectively to accompany the vision of a solar eclipse. Ever since, it has been used “as a portent of a significant event to come.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 – Nachtwandlerlied (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)