Celebrating his 60th birthday in 1863, Hector Berlioz was overcome by a “despair and disillusionment of appalling intensity.” Mourning the loss of two sisters and two wives, he became morbidly conscious of death. In 1864 he writes, “I am in my 61st year; past hopes, past illusions, past high thoughts and lofty conceptions. My son is almost always far away from me. I am alone. My contempt for the folly and baseness of mankind, my hatred of its atrocious cruelty, has never been so intense. And I say hourly to Death: ‘When you will.’ Why does he delay?”

Hector Berlioz in 1868

As a scholar writes, “And yet Berlioz lived another five years, suffering acutely from a form of intestinal neuralgia that had first appeared some ten years before and had reached severe proportions by 1859. Physical pain was never far away in the last 15 years, accentuated by his spiritual isolation.” Berlioz retired from composition and criticism, but he completed and revised his Mémoires. In the final pages, he paid tribute to his childhood idol Estelle, posing the question “Love or music, which power can uplift man to the sublimest heights? It is a large question, yet it seems to me that one should answer it in this way; love cannot give an idea of music, but music can give an idea of love. But why separate them? They are the two wings of the soul.”

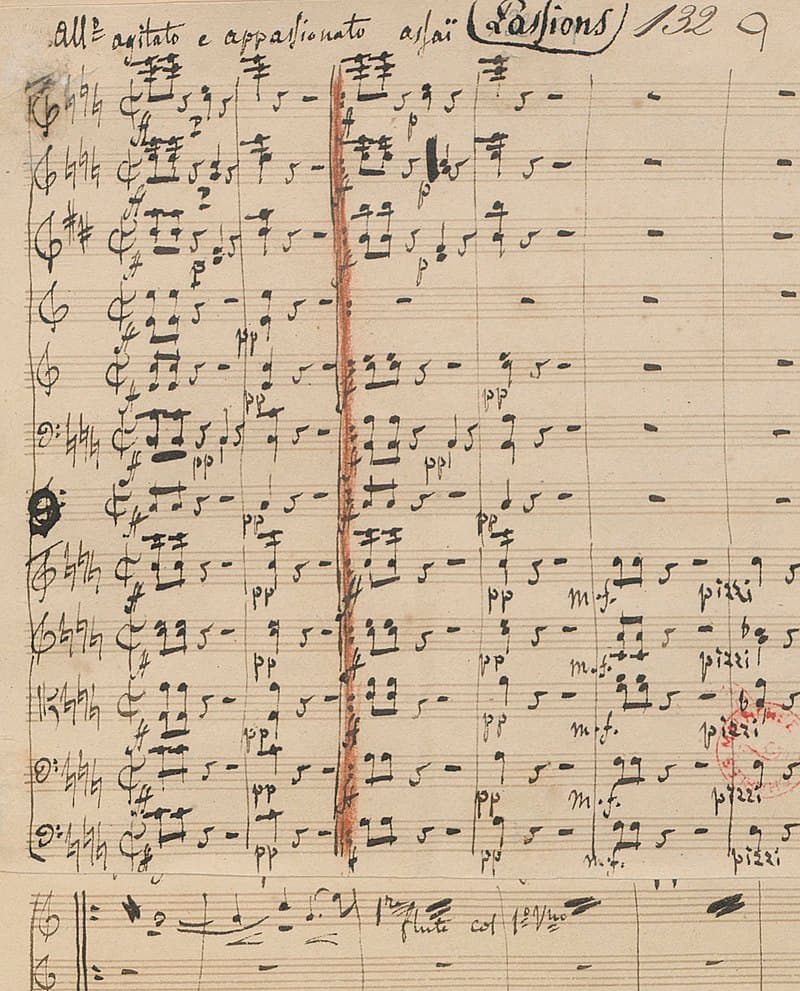

Hector Berlioz: Harold in Italy, Op. 16

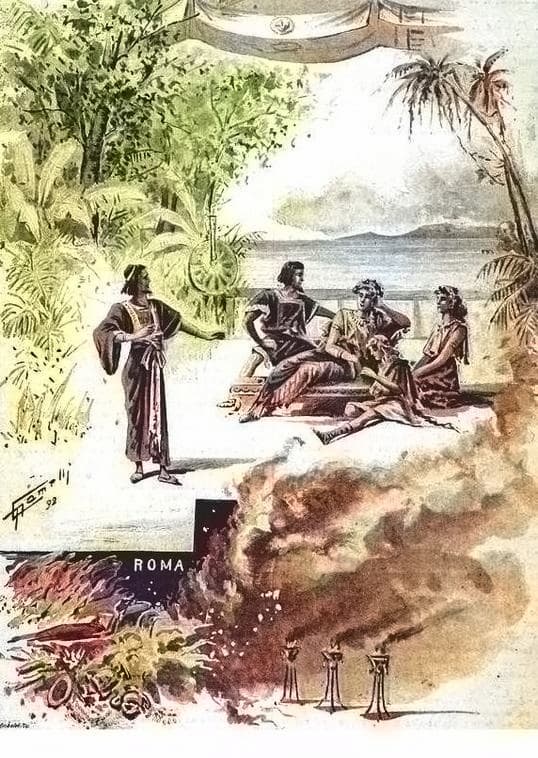

Scene from Les Troyens à Carthage

His infatuation with a young woman named Estelle Dubœuf dates back to the summer of 1815. He was only twelve and she was the eighteen-year-old niece of a neighbor. In his imagination, she became a literary conceit, and she knew nothing of his affections. As a biographer wrote, “her reaction upon learning of his love half a century later was one of perplexed amusement.” In 1864 Berlioz felt an overwhelming impulse to revisit the scenes of his childhood, especially Meylan, near Grenoble. Estelle was now a widow of 67, “yet the memory of their childhood encounter was fully alive in his mind.” As he wrote in his memoirs, “My soul leaped out towards its idol the moment I saw her as if she had still been in the splendor of her beauty.” He wrote her once a month and received her replies with great pleasure. However, his health continued to deteriorate and he was forced to take larger and larger doses of laudanum, which left him dazed and confused. And in June 1867, Berlioz received the news that his son Louis had died of yellow fever, in Havana, aged 32. About a week after receiving the news, he went to his office in the Conservatoire library and categorically burned letters, press cuttings, citations, and other artifact of his public and personal life.

Hector Berlioz: “Hymne pour la consécration du nouveau tabernacle” (Les Éléments Chamber Choir; David Bismuth, piano)

Score of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique – Passions

In the autumn of 1867, Berlioz was invited to conduct eight concerts in St. Petersburg and Moscow. He directed Gluck and four Beethoven symphonies. And while he had first protested against performing his own music, the Fantastic Symphony and parts of Faust and Romeo featured prominently. “However, it was with Harold in Italy that his career as a conductor ended.” The audience heartily applauded, and the young composers of the Russian school paid their due respects. Berlioz traveled directly to Nice and to Monte Carlo. Walking in rocky terrain, he fell head first on the rocks, “and was picked up dazed and bleeding.” A second fall, a day or two later, caused by cerebral congestion, was even more serious. He had to stay in bed for an entire week before he felt strong enough to make the train journey back to Paris. Upon his return, Berlioz was little more than a shadow “dragging out what had come to seem a meaningless existence.” Blaze de Bury reported meeting him one evening in the autumn. “I saw an apparition like a ghost, ashen, bent, shaking; even his eyes, those great, vital eyes, had extinguished their spark.”

Hector Berlioz: Les Troyens, Act IV, “Mais bannissons ces tristes souvenirs” (Michel Philippe, baritone; Jean-Luc Maurette, tenor; Francoise Pollet, soprano; Gary Lakes, tenor; Jean-Philippe Courtis, bass; Catherine Dubosc, soprano; Helene Perraguin, mezzo-soprano; Montreal Symphony Orchestra Chamber Choir; Montreal Symphony Orchestra; Charles Dutoit, cond.)

Grave of Hector Berlioz

The records for the final months of Berlioz’s life are practically non-existent. Apparently, the last entry in his account book, “in an almost illegible hand, dates from 4 February 1869.” At some point prior, Berlioz had suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. This was perhaps followed by a more severe stroke that left him without speech. According to some visitors, “Berlioz did sit up to greet them, but he could only smile.” Berlioz sank into a coma at the beginning of March, and he was surrounded by a handful of friends when he died on 8 March, shortly after noon. According to Ernest Reyer, Berlioz muttered, “they are finally going to play my music.” The funeral took place three days after his death, and “was celebrated with the moderate degree of pomp proper to a member of the Institute and an officer of the Legion of Honour.” Adolphe Sax saluted the coffin as it was carried from the house towards the recently completed Eglise de la Trinite to music from the Symphonie funèbre. The church ceremony featured the Allegretto of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, the march from Alceste, the “Hostias” from the Grande messe, and movements by Cherubini and Mozart. There were speeches at the gravesite, “but Berlioz would have recognized the authentic Parisian blunder which marred the service. The organist had barely begun to play the Septet “Tout n’est que paix autour de nous,” when it was cut off by the brass striking up Litolff’s funeral march for Meyerbeer.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Hector Berlioz: Requiem “Agnus Dei”