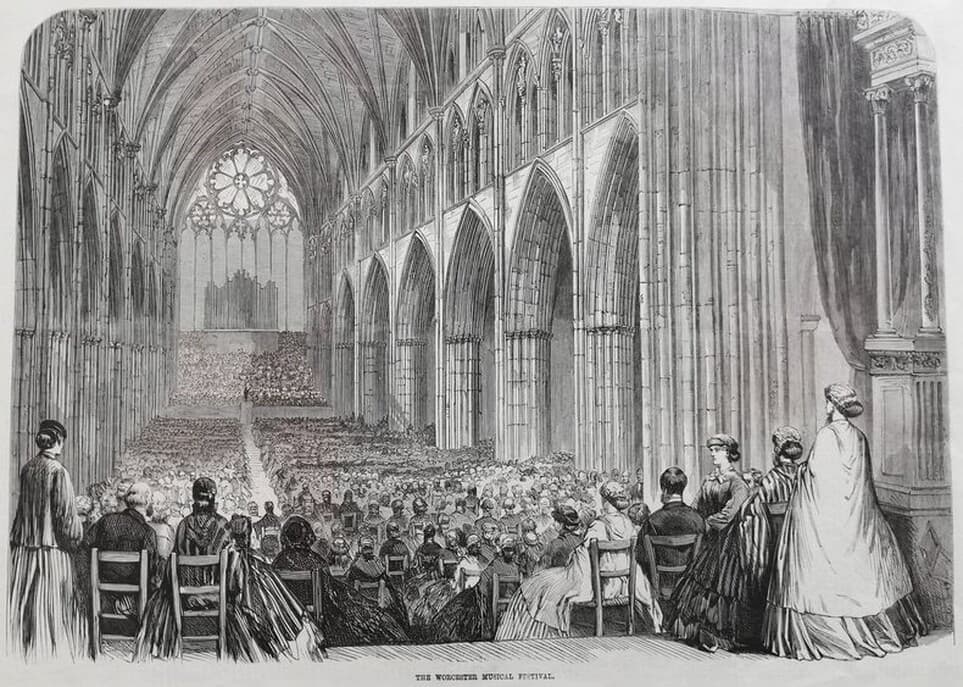

Over 300 years ago, the three Choirs of the cathedrals of Hereford, Gloucester, and Worcester decided to hold an annual music festival at the end of July. The origins of the annual music meetings of the “Three Choirs” were outlined in a 1729 sermon preached by Thomas Bisse at Hereford Cathedral, who said, “it had a very small and accidental origin. It was… a fortuitous and friendly proposal, between a few lovers of harmony and brethren of the correspondent choirs, to commence an anniversary visit, to be kept in turn; which voluntary instance of friendship and fraternity was quickly strengthened by social compact; and afterwards, being blessed and sanctioned by a charity collection, with the word of exhortation added to confirm the whole, it is arrived to the figure and estimation as ye see this day… Upon these grounds it commenced, and upon these let our brotherly love continue.”

The Worcester Music Festival

The first “Annual Music Meeting of the Three Choirs” is believed to have taken place in Gloucester in 1715. Since then, World Wars have interrupted the festival twice, from 1914 to 1920, and from 1939 to 1945, and Covid-19 forced a cancellation in this century. Nevertheless, the “Three-Choirs Festival” is the longest-standing classical music festival in the world. The festival has prided itself on bringing new works to its audiences, and in this blog, we explore works commissioned especially for and premiered at the festival.

Hubert Parry: De Profundis (2nd Movement)

Sir Hubert Parry wrote a series of large choral works in the late 1880s and early 1890s, including the Biblical oratorios Judith (1888) and Job (1892), and the cantata Ode on St Cecilia’s Day (1889). His psalm setting De Profundis was written for 12-part choir, orchestra and soprano soloist, and premiered at the Three Choirs Festival in 1891.

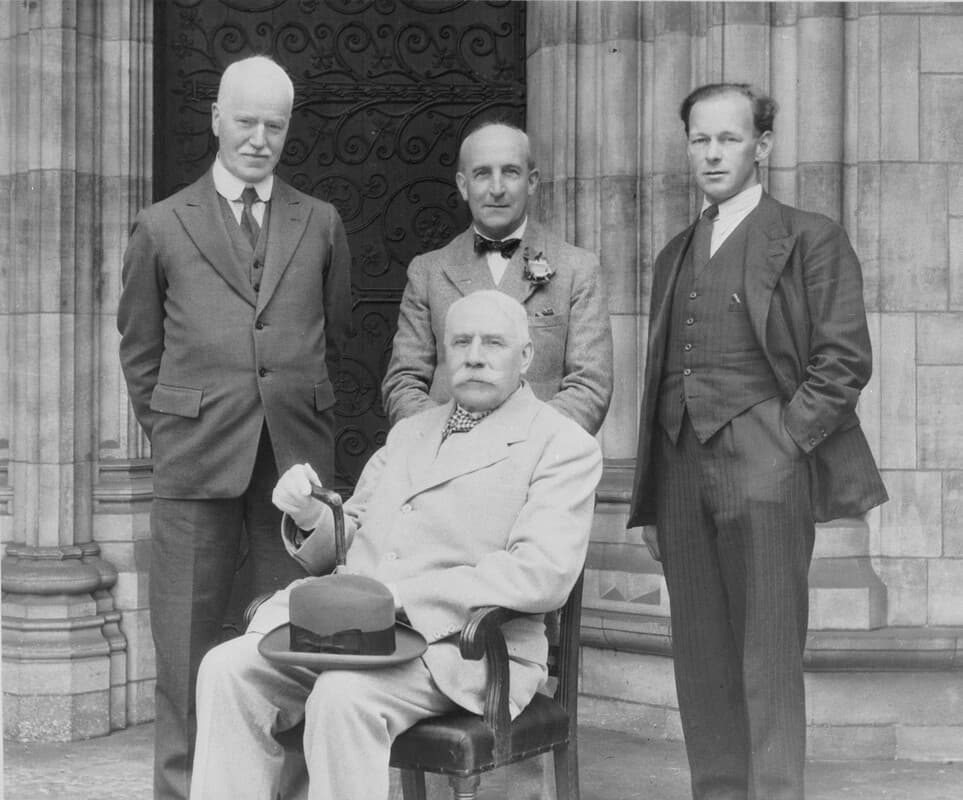

Sir Hubert Parry, 1916

The premier performance did not unfold as planned, as the lack of rehearsal time had its consequences. Parry noted in his diary, “Terrible performance of De Profundis. 1st Sopranos came in a bar too soon in the opening passage and ruined it, and it all went as flabbily as possible.” None withstanding, a contemporary critic wrote, “The composer conducted a production of very remarkable merit which will assuredly come to be received as a masterpiece and remembered as one of the chief events of the Festival.” The work did receive further performances, but after Parry’s death in 1918, it decidedly fell out of favor. For the Parry centenary in 1948, Ralph Vaughan Williams wrote to Sir Adrian Boult. “It seems to me a scandal that during the Parry celebrations, his finest work, De Profundis, should not be done… Please insist on its being done, and soon.”

Camile Saint-Saëns: The Promised Land, Op. 140

On 1 August 1913, The Musical Times reports, “At an age when most musicians are seeking for retirement and rest, Saint-Saëns, the most versatile and scholarly of the musicians of our time, is seeking new worlds to conquer… He was asked to write an English oratorio to a text arranged from the English Bible and intended for production before an English audience.” The Promised Land, also known as La Terre Promise started as a commission by the English publisher Novello. Saint-Saëns asked the music critic and author Herman Klein to arrange the Biblical text for an oratorio originally called The Death of Moses and slated for performance in Norwich. Saint-Saëns was adamant that “Moise will probably be my last work. It must worthily crown my career.” In the event, Norwich authorities shelved the project, but it was then selected for the Three Choirs Festival of 1913 with the composer conducting his work at Gloucester Cathedral. As a critic writes, “Saint-Saëns would seem to have borne in mind the traditions of oratorio which are dear to English people. Save in the broadest sense, he has not attempted to make a connected drama of his work but has regarded it as a mixture of narrative, drama, and reflection.”

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Five Mystical Songs

Born in Gloucestershire, Ralph Vaughan Williams is closely associated with the Three Choirs Festival, which in his lifetime hosted no fewer than nine premières of his works. 1910 saw the premiere of the Tallis Fantasia at Gloucester, and the Fantasia on Christmas Carols first sounded in 1912. Sandwiched in between, Vaughan Williams conducted the first performance of Five Mystical Songs at the Worcester Meeting in 1911.

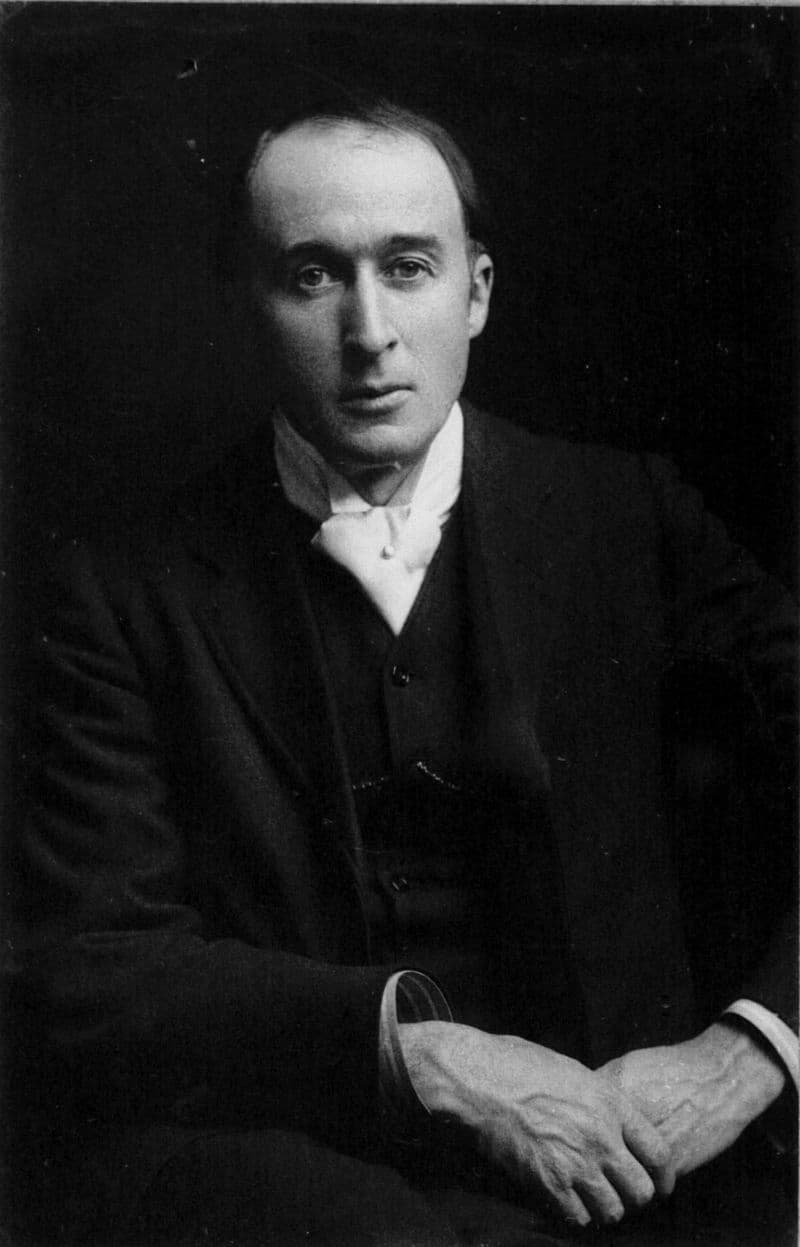

Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1898

“Not a bad hat-trick,” a scholar writes, “as each of these works has gained a permanent and much-loved place in the repertoire.” For his settings of Five Mystical Songs, Vaughan Williams turned to the Welsh poet, orator and priest of the Church of England, George Herbert. Working in the first quarter of the 17th century, Herbert is “recognized as one of the foremost British devotional lyricists.” Through his involvement with the English Hymnal, Vaughan Williams had developed “a most instinctive and natural feel for word setting and vocal characterization.” The poems are placed within a sound environment of tonal ambiguity and freedom of key and “a sure ear for instrumental colour and contrast.” Throughout his career, Ralph Vaughan William attempted to re-create the poems as music, and “singing Herbert’s words invokes a joy too deep for words.” As a scholar writes, the Five Mystical Songs “probe this joy and suggest a deeply-rooted complementarity between poems and songs occasioned by the composer’s re-creation.”

Zoltán Kodály: Missa Brevis (version for choir and orchestra) (Maria Gyurkovics, soprano; Edit Gancs, soprano; Timea Cser, soprano; Magda Tiszay, contralto; Endre Rosler, tenor; Gyorgy Littasy, bass; Budapest Chorus; Hungarian State Orchestra; Zoltán Kodály, cond.)

George Herbert

Herbert Whitton Sumsion was organist of Gloucester Cathedral from 1928 to 1967. Through his leadership role with the Three Choir Festival, he maintained a close association with major figures in England’s 20th-century musical renaissance. A former student writes, “Sumsion’s vision in matters of programme planning, together with his skill of direction in a very wide spectrum of works, made him one of the most successful conductors in the Three Choirs Festival’s history. For almost five decades he was responsible for planning and serving as the principal conductor for eleven festivals held at Gloucester.” And while Sumsion championed the performance of new English works, he maintained a close festival connection with Zoltán Kodály, programming his works at six Gloucester festivals. Kodály visited England for the first time in 1927, and a performance of his Psalmus Hungaricus was repeated at the Three Choirs Festival in 1928. When Kodály recalled his first visits to England in 1927 and 1928 in a lecture at the British Embassy in Budapest in 1960, he remarked: “that the English masterpieces of the 16th century, which were not inferior to contemporary Italian compositions, were rediscovered and published again.” He went on to cite this, alongside the discovery of folksong, “as the main factors of the musical rebirth of England.” Kodály took part in the Three Choirs Festival for the last time in September 1948. His Missa Brevis, originally composed for mixed chorus and organ at the end of the Second World War, first sounded in an orchestrated version at Worcester on 9 September 1948.

Edward Elgar: Froissart Overture

Growing up in Worcester, young Edward Elgar would listen to his father and uncle rehearsing Beethoven’s Mass in C for the Three Choirs Festival. In fact, by 1878 he would play second violin in the festival orchestra himself. However, his relationship with the festival got off to a rocky start. “As a Roman Catholic by upbringing, he often felt a bit of an outsider in the Anglican cathedral world, and he could be impatient with the conservative musical tastes of the festival committees.”

Edward Elgar at Hereford Cathedral, 1933

When the 1890 Worcester Festival once more asked for a commission, Elgar looked for inspiration in the Middle Ages. His choice fell on Jean Froissart, a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries. He wrote a long Arthurian romance and a large body of poetry, both short lyrical forms as well as long narrative poems. His writings “have been recognized as the chief expression of the chivalric revival of the 14th-century kingdoms of England, France and Scotland.” In the event, “Froissart” turned out to be Elgar’s first major work for orchestra and was premiered at the Three Choirs Festival in 1890. Press comments following the premiere were generally favorable, although some critics “suggested that the overture would be better described as the impression of a romantic period than the portrayal of any particular sequence of events.” To be sure, Elgar always insisted that the overture does not tell any connected story of action and character. Rather, “it is an expression of feeling inspired by the character and ambience of a place or an age.”

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: Ballade for Orchestra, Op. 33

In 1898, the Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester offered Edward Elgar a commission. He responded, “I have received a request from the secretary to write a short orchestra thing for the evening concert. I am sorry I am too busy to do so. I wish, wish, wish you would ask Coleridge-Taylor to do it. He still wants recognition, and he is far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the young men. Please don’t let your committee throw away the chance of doing a good act.” Herbert Brewer, who was overseeing his first Three Choirs Festival, agreed and recommended Samuel Coleridge-Taylor to his committee. The recommendation was approved on 28 May, with a performance scheduled for 12 September 1898. On that day, Coleridge-Taylor conducted his Ballade for Orchestra at the Shire Hall, and the orchestra gave him a standing ovation at rehearsal. Elgar did hear the work during an earlier rehearsal and delightedly wrote, “I liked it all and loved some and adored a bit.” It is a work full of “wonderful high-spirits, passion and warmth, and the lyrical second subject is a joyous melody, magnificent in its soaring flight.” Coleridge-Taylor was once again commissioned in 1899 and provided the Solemn Prelude, Op. 40. Despite its successful premiere in 1899, the full score was never published, and the orchestral material was lost, with only the composer’s own piano reduction ever released.

Frederick Delius: A Dance Rhapsody No. 1 (Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

Frederick Delius

Frederick Delius was commissioned to compose and conduct the premiere of his Dance Rhapsody No. 1 at the Hereford Three Choirs Festival in 1909. Almost instantly, it became one of his most performed pieces during his lifetime. Thomas Beecham left a flamboyant account of the First Dance Rhapsody’s premiere, writing, “Delius delegated a prominent part to the rarely encountered bass oboe, and for the occasion, only a lady amateur could be found to play it. Now the bass oboe… is to be endured only if manipulated with supreme cunning and control… a perfect breath control is an essential requisite for keeping it well in order, and this alone can obviate the eruption of sounds that would arouse attention even in a circus. As none of these safety-first precautions had been taken, the public… was confounded by the frequent audition of noises that resembled nothing so much as the painful endeavor of an anguished mother duck to effect the speedy evacuation of an abnormally large-sized egg…” The work is cast in variation form, with the dance theme journeying through different keys and rhythmic alterations. A central section features a rhapsodic violin solo that only gradually reveals its relationship to the principal dance theme. Peter Warlock wrote, “Though the outward form of the work is of the crudest and simplest character, its spiritual curve, so to speak, is wholly satisfactory.”

John Singer Sargent: Dame Ethel Smyth

Ethel Smyth did not compose her Mass in D specifically for the Three Choirs Festival. However, she did conduct two movements from the Mass at the 1925 festival and returned in 1928 to conduct the entire work. The Mass had been completed in 1891, after a period of travel that had seen Smyth study at the Leipzig Conservatory. She had also visited Munich, and attended concerts with music by Wagner and Beethoven. Apparently, the one work that impressed her greatly was Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis. The premiere of her Mass took place at a concert by the Royal Choral Society in 1893, where it was paired with Haydn’s Creation. The work was revised and not heard again until 1924, and subsequently appeared at two Three Choirs Festivals. The critic for the Musical Times writes on 1 October 1928, “Ethel Smyth’s Mass in D was a quasi-novelty. It aroused admiration, respect and astonishment rather than affection. To obtain from it the full measure of surprise, one has to think of it not as having been written by a woman—Dame Ethel objects to that circumstance being considered at all—but as a product of any English composer working in the eighteen-nineties. It is easy to point to faults…but the Mass remains an indisputable vital piece of music that, having at long last obtained a measure of recognition, deserves to receive much more.” The Three Choirs Festival, over the centuries, has also given voice to premier performances composed by Gustav Holst, Arthur Sullivan, Herbert Howells, Gerald Finzi, William Walton, Arthur Bliss, Benjamin Britten, Judith Weir, Judith Bingham, James MacMillan, Lennox Berkeley, John McCabe, William Mathias, Paul Patterson, and Cheryl Frances Hoad, among countless others. With so many additional premier performances to explore, could you please let us know in your comments which compositions we might feature in a follow-up article?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter