One of the most important Polish composers of the 20th century, Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) is a reflection of the most relevant currents and trends in music during his life. Initially fascinated by the music of Chopin and Wagner, Szymanowski’s music is a great example of the creative collation from varied sources of inspiration. It reaches “from the cultural heritage of Europe, based on a dialogue of the North and South, East and West, to the exotic impulses of Oriental culture.” In this blog, we take a closer look at his remarkable 9 Preludes, Op. 1, composed between 1899 and 1900, and published in 1906.

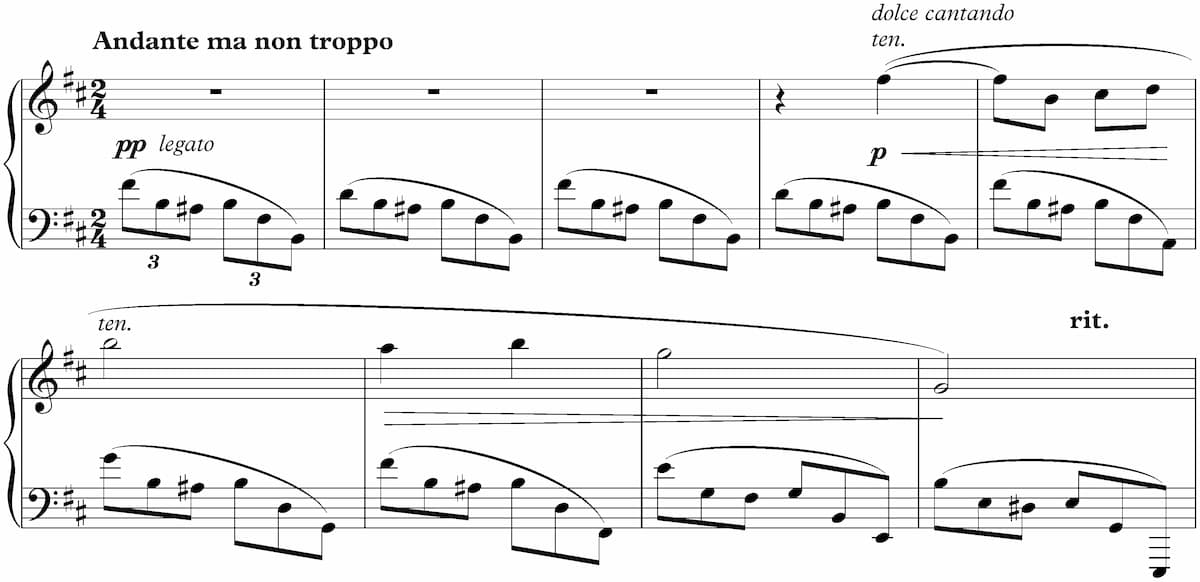

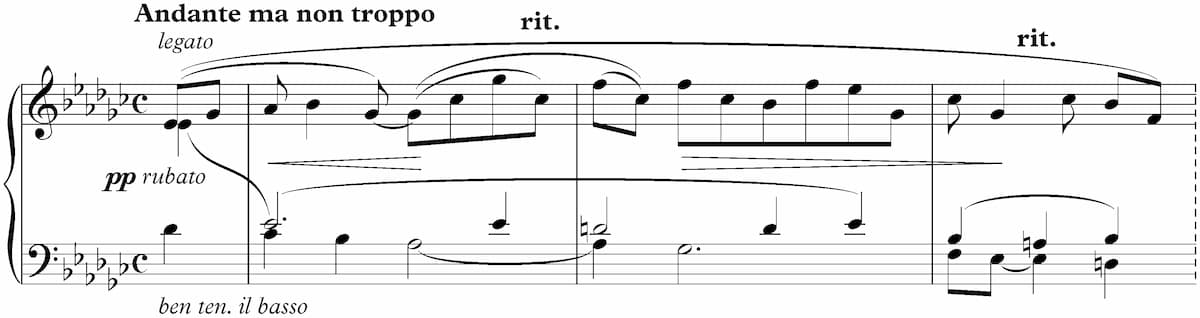

Beginning measures of Szymanowski’s 9 Preludes, Op. 1 No. 1

Karol Szymanowski: 9 Preludes, Op. 1, No. 1 “Andante ma non troppo” (Krystian Zimerman, piano)

Origins

Portrait of Karol Szymanowski by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz

For a good many years, there was much confusion surrounding Szymanowski’s date of birth. His first biographer incorrectly recorded it as 6 October 1882, with Szymanowski claiming to have been born in 1883. Finally, in 1980 his true date of birth was reliably established in three separate, unrelated documents. From his baptismal certificate, we definitively learn that he was christened according to the rites of the Roman Catholic church on 21 October 1882, in the Russian old style, and actually born on 3 October 1882, in the new calendar style.

Confusion notwithstanding, Szymanowski was born in the Ukraine into a family of high intellectual culture. His ancestry traces back to wealthy land-owning Polish gentry expelled to the Kiev region following the Polish uprising against Russia and Prussia. His grandfather Feliks was an outstanding musician, and he moved the family to the village of Tymoszówka. His father Stanislaw administered a large estate, which included a lake and an extended orchard. Stanislaw was also an ardent music lover, and responsible for providing initial musical instructions to his son.

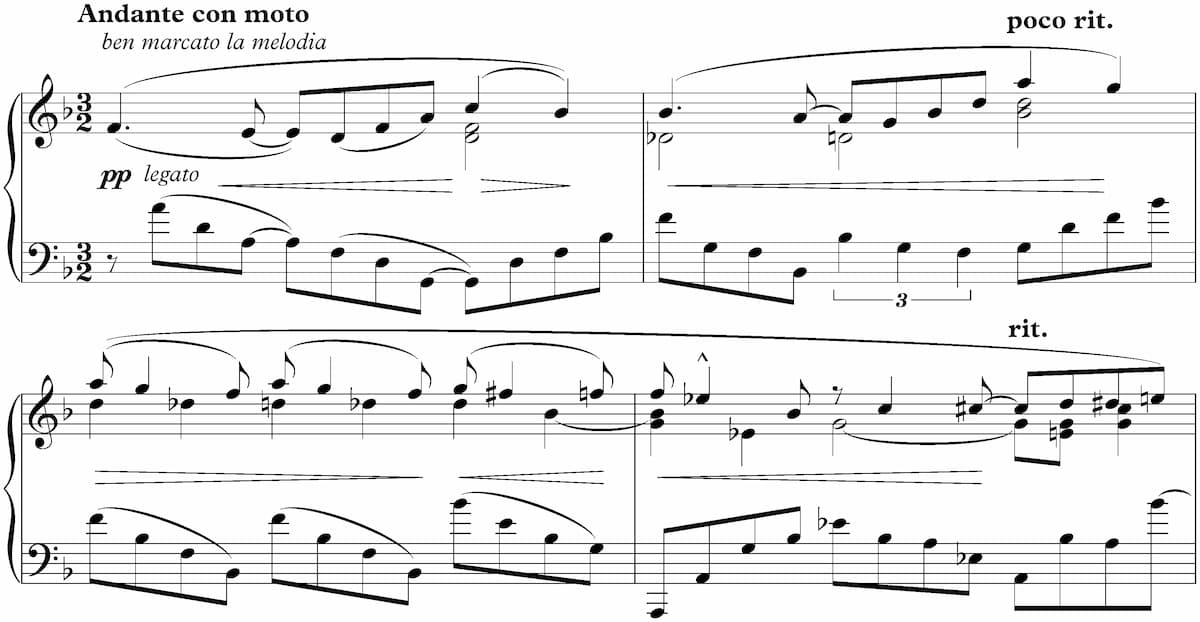

Beginning measures of Szymanowski’s 9 Preludes, Op. 1 No. 2

Karol Szymanowski: 9 Preludes, Op. 1, No. 2 “Andante con moto” (Krystian Zimerman, piano)

Karol’s mother, Anna, substantially younger than her husband, was known as “Madame la Marquise” in certain quarters of the family. She led a hectic social life and travelled extensively, but for Karol, she was the most loved and revered member of the family. To be sure, music ran definitely in the family. His brother Zygmunt was a singer and composer, his second brother Stanislaw a music teacher and owner of a school of music in Kiev, his sister Joanna was a singer, and his second sister Marta, a pianist.

The Szymanowski’s were related to a number of highly musical families, among them the Blumenfeld’s originally from Bavaria, and the Neuhaus family originally from the Rhineland. Marta Blumenfeld had married the music teacher Gustav Neuhaus, and they jointly operated a school of music in Yelisvetgrad, now Kirovograd. This school was attended by every one of the Szymanowski children, including Karol who enrolled in 1892.

Beginning measures of Szymanowski’s 9 Preludes, Op. 1 No. 3

Karol Szymanowski: 9 Preludes, Op. 1, No. 3 “Andantino” (Matthias Roth, piano)

Childhood Injury

Szymanowski had a traumatic childhood, as he sustained a leg injury at the age of 4. He was unable to walk for several years, and the injury left a slight limp for the rest of his life. Instead of enjoying a carefree childhood with friends and outdoor games, books and musical scores became his emotional refuge. He received a patchy formal education from various home tutors, but by his teens, in addition to his native Polish, he was fluent in French, German, and Russian. From his earliest years, he was interested in the natural sciences, the fine arts, and philosophy.

Szymanowski’s childhood was shaped by two important musical events. At the small theatre in Yelisavetgrad, young Szymanowski listened to the popular opera Rusalka by Alexander Dargomizhsky, and the magical world of opera fundamentally influenced his career choice. And secondly, on his way to Geneva to solve some problems with an inheritance, Szymanowski stopped in Vienna and saw Wagner’s Lohengrin, which introduced him to the chromatic functionality of harmony. As he wrote, “henceforth Wagner became the sole object of my dreams. And I came to know all his works from piano reductions.”

Beginning measures of Szymanowski’s 9 Preludes, Op. 1 No. 4

Karol Szymanowski: 9 Preludes, Op. 1, No. 4 “Andantino con moto” (Barbara Karaśkiewicz, piano)

A Musical Household

As Szymanowski later remembered, “Although far away from major musical centres, thanks to my highly musical surroundings I became accustomed to the best music from my youngest years. My earliest musical memories are of Chopin, Bach, and especially Beethoven.” The Szymanowski household was indeed a beehive of musical activities. As a contemporary reported, “Almost every family get-together transformed the drawing room into a concert hall. Libretti and music for operettas were written on the spot, stage decor was quickly painted, and instant performances took place on an improvised stage.”

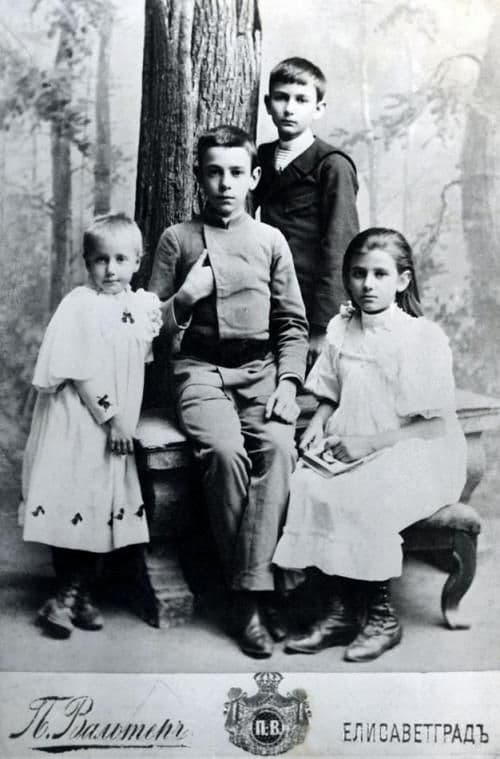

Karol Szymanowski and his siblings

Karol had long dabbled in composition, writing piano pieces and songs that could be performed in the family circle. He composed for and at the piano from his early youth right up to his last opus, and his close relationship with the instrument manifests itself in his entire output. A good many preludes, études, and other piano miniatures from this juvenile period have not survived, but the eighteen-year-old composer burst onto the music scene with his Nine Preludes, immediately astonishing listeners and professionals.

Beginning measures of Szymanowski’s 9 Preludes, Op. 1 No. 5

Karol Szymanowski: 9 Preludes, Op. 1, No. 5 “Allegro molto impetuoso” (Alicja Fiderkiewicz, piano)

Nine Preludes

The Polish musicologist Zofia Helman saw the set “shaped on Chopin’s patterns but directed towards contemporaneity.” Szymanowski was clearly fascinated with Chopin during his youth, and he transferred the character of Chopin’s melodic ornamentation and melodic figuration into his 9 Preludes. These early pieces, however, are not merely curiosities but “an authentic expression of a youthful emotionalism.”

Szymanowski at the piano

Szymanowski saw his chief emotion of a teenage as “truly of unbearable, agonising, constant suffering. Involuntarily I came into this unpleasant, hideous adventure of life, full of terrible surprises.” His psychologic profile might well have seeped into his musical language, as he develops motives through harmonic changes and the use of polyrhythms. In a way, Szymanowski is already looking towards the innovative harmonic language of Alexander Scriabin, encoding richly dissonant chords and creating emotionally outlined climaxes.

Beginning measures of Szymanowski’s 9 Preludes, Op. 1 No. 6

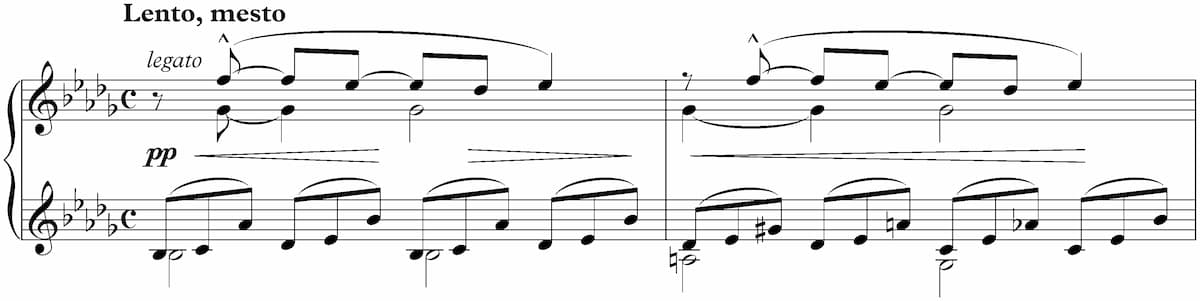

Karol Szymanowski: 9 Preludes, Op. 1, No. 6 “Lento mesto” (Matthias Roth, piano)

Written by a Master

The pianist and composer Arthur Rubinstein wrote after studying the score, “There is no way to describe our amazement after playing the first few bars of the Prelude. This music has been written by a master! Frantically we have read all the manuscripts, and our enthusiasm and excitement grew, as soon as we realized that here we are discovering a great Polish composer.”

And a contemporary added, “being in our area of a dazzling novelty, these pieces have begun the process of catching up and overtaking the European musical technique.” His keyboard textures come across as orchestral and multi-layered, yet they display a markedly introverted character. This music never panders to the listener or resorts to external effects, but “it is always substantial and compelling.”

Beginning measures of Szymanowski’s 9 Preludes, Op. 1 No. 7

Karol Szymanowski: 9 Preludes, Op. 1, No. 7 “Moderato” (Krystian Zimerman, piano)

An Eyewitness

A fellow student at the Warsaw Conservatory remembers, “Szymanowski was not able to work with bureaucratic regulatory, but once he had started on a composition or a part of it, he would spend hours sitting over his music paper in deep concentration, covering the whole sheet with minute notes.”

“When he was composing for the piano, he studied the structure of piano passages by Chopin and Scriabin with an utmost thoroughness. For him this music contained the secrets of piano style, and he knew how to unravel them. In fact, every one of his piano passages already possess excellent pianist qualities, even at that time.”

Beginning measures of Szymanowski’s 9 Preludes, Op. 1 No. 8

Karol Szymanowski: 9 Preludes, Op. 1, No. 8 “Andante ma non troppo” (Krystian Zimerman, piano)

Lyrical Miniatures

For the most part, the 9 Preludes are lyrical miniatures, and despite the fact that they obviously owe a lot to Chopin, these pieces form a remarkably mature and coherent whole for a beginning composer. Relatively simple in texture and soft-spoken in sound, they disclose a rich chromaticism and a multi-layered texture.

The opening prelude is the most reduced, with the melody in the right hand supported by a single accompanying voice. Prelude No. 5 foregoes this restrained and serene character and sounds a harsh and uncompromising miniature that is finally released in the concluding chord. Pianists consider the A-minor Prelude No. 6 the most original, as it progressively takes shape in the style of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. With this huge dramatic arc, this tiny miniature grows to Wagnerian proportions, a herald of his later colossal output. The concluding Prelude, in turn, appears to take its bearings from the miniatures of Claude Debussy.

Already in his Nine Preludes, Szymanowski shows a characteristic which was to become a feature of the majority of his best works, namely, a strong emotional tension which sometimes intensifies into ecstasy. Szymanowski’s experience of music was, above all, emotional. Everything he composed he had first experienced on the deepest emotional level, even if he then transcribed it into a musical language that was not immediately comprehensible to everyone.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Beginning measures of Szymanowski’s 9 Preludes, Op. 1 No. 9

Karol Szymanowski: 9 Preludes, Op. 1, No. 9 “Lento mesto” (Barbara Karaśkiewicz, piano)