Clara Schumann

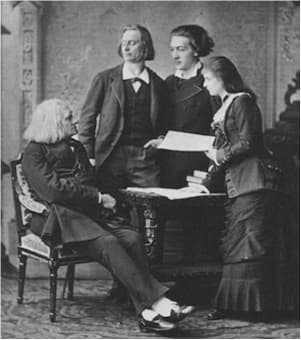

Franz Liszt was the greatest piano virtuoso of his time; possibly the greatest of all time! His sensational technique and captivating concert personality turned him into the ultimate rock star of the 19th century. However, this notoriety also created uncertainty, as Franz was never sure that he was, in fact, truly liked or loved. In the end, the only person Franz ever really loved, was the reflection of himself he had created. And as you might well imagine, an extended circle of friends, wannabe friends, groupies, and socialites constantly fluttered around him like moths to a flame. And for a time that included Clara Wieck. Clara first heard Franz Liszt in concert in Vienna, and she was flabbergasted. “He can be compared to no other virtuoso,” she writes. “He is only one of his kind. He arouses fright and astonishment, though he is a very lovable artist. His attitude at the piano cannot be described, his passion knows no limits, and he has a great spirit.” Delighted by the glowing endorsement of a fellow pianist, Liszt dedicated his Six Etudes d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini to Clara.

Franz Liszt: Paganini Etude No. 2

Alphonse de Lamartine

Liszt strongly supported Robert and Clara in their legal battle to get married, but some misunderstandings soured the relationship. Liszt apparently denied Clara’s request for tickets for her father, and although she continued to admire his virtuosity, Clara did not agree with his public image. As she famously quipped, “Liszt gives me the impression of being a spoilt child.” Only a decade earlier, Liszt had lavished in obscurity in Paris, having outgrown his career as a dazzling child prodigy of the piano. At the age of 20, Liszt made a meager living giving private piano lessons, and he tried his hands at original compositions. But then he discovered the French poet and politician Alphonse de Lamartine, who had achieved unparalleled popularity with his first volume of poetry, the Méditations poétiques. The Lamartine family and Franz Liszt became good friends, and Liszt’s first truly original composition, the Harmonies poétiques et religieuses bears the exact Lamartine literary title. Liszt eventually disavowed this first effort to express Lamartine in music, and restructured the harmonies into a cycle of ten pieces. Four Harmonies are prefaced by direct quotations from the poetry, including the “Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude.”

Franz Liszt: Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, “Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude” (Brigitte Engerer, piano)

Olga von Meyendorff

Liszt’s daughter Cosima described Baroness Olga von Meyendorff as “unfortunately very unpleasant, disdainful and arrogant.” Olga had been the wife of the Russian ambassador to the Court of Weimar, but he unexpectedly died after less than a year in office. Olga quickly found refuge in Liszt’s arms and for the next sixteen years they frequently traveled together. Liszt’s American student Amy Fay writes, “This haughty countess has always had a great fascination for me, because she looks like a woman who has a history. I have often seen her at Liszt’s matinees, and from what I hear of her, she is such a type of woman as I suppose only exists in Europe. She makes an impression of icy coldness and at the same time of tropical heat; the pride of Lucifer to the world in general!” During the last sixteen years of Liszt’s life, he wrote no less than 400 letters to Baroness Olga, who shared his interests, although not always his views, on a broad field of disciplines ranging from music, philosophy, theology, politics, and literature. And he also dedicated some music to the haughty Baroness.

Franz Liszt: 5 Kleine Klavierstücke (Paul Lewis, piano)

Frédéric Chopin

Franz Liszt attended Chopin’s début at the Salle Pleyel on 26 February 1832. According to Liszt, “The most vigorous applause seemed not to suffice to our enthusiasm in the presence of this talented musician, who revealed a new phase of poetic sentiment combined with such happy innovations in the form of his art.” Chopin happily reciprocated with the dedication of his set of 12 Etudes Op. 10 to Liszt. And Liszt’s Duo Sonata based on Polish themes and composed in 1835 is a musical tribute to Chopin. The four movements are based around Chopin’s Mazurka in C sharp minor, Op. 6 No. 2, with an injection of other Polish material along the way. They shared a mutual admiration for each other, but it would be a stretch to classify their relationship as a great friendship. Liszt was enamored by the simplicity and poetic atmosphere of Chopin’s compositions, but Chopin soon came to dislike what he perceived to be Liszt’s theatricality. Nevertheless, Liszt and Chopin collaborated in a few concerts and frequently interacted with the various artistic and intellectual circles of the city. However, any chance of a deep and meaningful relationship was made impossible because their partners George Sand and Marie d’Agoult hated each other!

Franz Liszt: Duo Sonata, S127/R461 (Voytek Proniewicz, violin; Wojciech Waleczek, piano)

Sophie Menter

Sophie Menter (1846-1918) gave her pianistic debut at age 15, and she took further lessons with the Liszt pupil Carl Tausig. She soon appeared in concerts throughout Europe. Her very first concert in Leipzig featured a composition by Franz Liszt, and the E-flat major concerto became her signature piece. “Miss Menter,” a critic wrote, “deserves the praise of all the other performers of this concert for having reproduced the witty composition in accordance with its true intention.” Liszt visited the young pianist in Vienna in March 1869, and established a lifelong acquaintance that was characterized by mutual esteem. Although Liszt called her “my only legitimate piano daughter,” Menter was not actually one of his students. Rather, they looked at each other as colleagues, visited each other and made music together. In the last letter of his life from 3 July 1886, Liszt invited Menter to Bayreuth, where she stayed with him until his death. After Liszt’s death, Menter completed sketches believed to have been part of a piano concerto that Franz Liszt had planned to write for her. She enlisted the help of her friend Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, who furnished the orchestration. The work entitled Hungarian Gypsy Melodies premiered in Odessa on 4 February 1893.

Liszt/Menter/Tchaikovsky: Hungarian Gypsy Melodies (Andrei Hoteev, piano; Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra; Vladimir Fedoseyev, cond.)

Abbé Felicité de Lamennais

Between 1827 and 1832, Franz Liszt lived with his mother in a small apartment. He made a living giving piano and composition lessons, and overcame his lack of general education by becoming a voracious reader. He came into contact with many of the leading authors and artists of his day, including Victor Hugo, Alphonse de Lamartine and Heinrich Heine. When an unhappy love affair raised religious doubts and pessimism, he fell under the spell of the Saint-Simonians, who looked to combine socialism with the teachings of Christ. Liszt attended secret meetings of the sect at their headquarters, but once police had raided the dwelling and arrested the leaders, he turned to Abbé Felicité de Lamennais for spiritual advice. Liszt described Lamennais as a “saint,” and visited him at his home at La Chênaie, in Brittany, where he stayed for several weeks. Lamennais advocated freedom of consciousness, of speech and the press, the abolition of the death penalty and the separation of Church and State. Not unexpectedly, he was excommunicated in 1836. Lamennais came to regard Liszt as “one of the most beautiful and noble souls that I have met on this earth.” And it was at La Chênaie that Liszt composed his Apparitions for piano.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: Apparitions S155/R11 (Bogdan Czapiewski, piano)

“In the end, the only person Franz ever really loved, was the reflection of himself he had created. ”

Have you read any biographies before saying that? Among many composers I found Liszt very full of humanity. Read Friedheim’s memoirs of Liszt. Watch Lachmund (another pupil) talk about him on Youtube. So many students wrote about him and they’re all fun to read.

Totally agree! the description in the article of Liszy being someone who “only loved himself” is laughably untrue! – it applied far more to people like Chopin and Berlioz than it ever would have of Liszt, both of whom ignored most of Liszt’s music even after he had tirelessly promoted theirs! So much rubbish based on gossip was written about Liszt over the years, most damagingly by the critic Ernest Newman, who scurrilously penned what was regarded as “the definitive Liszt biography” without ever leaving England to do any proper research on his subject – to this day, Liszt is subjected to “poison-pen” treatment based on heresay rather than researched opinion. Thankfully

Alan Walker’s recent three-volume biography of Liszt has done much to “right the wrongs” perpetrated by the “Liszt legend”, but amongst musicians and music-lovers Liszt’s music continues to divide opinion, even if his legendary “womanising” activities have largely been disproven by Walker’s meticulous researchings.