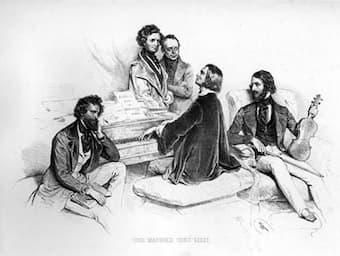

Berlioz and Liszt, 1846

Franz Liszt first met Hector Berlioz a few months after the July Revolution. He attended the first performance of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique in the company of the composer on 5 December 1830. Almost immediately, Liszt started work on his piano transcription. “I have started something quite different with my transcription,” he writes. “I have worked on this as conscientiously as if I were transcribing the Holy Scriptures, attempting to transfer to the piano not only the general structure of the music but all its separate parts, as well as its many harmonic and rhythmic combinations.” Berlioz and Liszt developed a warm friendship that lasted the better part of 20 years. Berlioz does speak of Liszt with a good deal of affection in his Mémoires, and he clearly regarded him unrivalled as a pianist. However, he was much more guarded about Liszt’s orchestral compositions, and when Liszt whole-heartedly endorsed Richard Wagner, the relationship soured beyond repair.

Berlioz/Liszt: Symphonie fantastique, “Un Bal”

Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein

Franz Liszt met Princess Carolyne von Sayn-Wittgenstein during a concert in Kiev in February 1847. She was seven years younger than Liszt and separated from her husband, Prince Nicholas von Sayn-Wittgenstein, whom she was forced to marry at age 17. Carolyne followed Liszt to Weimar. Carolyne was much more than simply Liszt’s lover and companion; she was his best friend. “All my joys come from her,” Liszt writes, “and all my sorrows go to her to be appeased.” Biographers had frequently marginalized Carolyne, dismissing her as “a half-cracked blue stocking” who constantly meddled in Liszt’s affairs. Liszt clearly thought otherwise, as she was receptive to his ideas and sympathetic to his artistic aims. In fact, without Carolyne’s support a growing body of one-movement orchestral compositions termed symphonic poems would probably not have been composed. Programmatically conceived, Liszt composed 12 such symphonic poems in Weimar and all are dedicated to Princess Carolyne.

Franz Liszt: Prometheus (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Georg Solti, cond.)

Lina Ramann

Lina Ramann (1833-1912) was a highly influential author and music pedagogue writing on the state of women and fighting to have her works equally represented. Combining general philosophical education with music teaching, she founded two schools for women teachers and traveled to the United States to bring music to rural communities. She was the author of a good number of books on music, and Franz Liszt was her preferred subject. She wrote a three volume Liszt biography, and conducted extensive research into his life. In fact, she sent him a 37-page questionnaire asking questions of a biographical and music-analytical nature. It is said that her personal interviews with Liszt also included heated discussions and exchanges with Princess Carolyne! Ramann prided herself as being entirely objective in her assessment of Liszt, and the composer dedicated one of his most demonically difficult piano compositions to her.

Franz Liszt: Grosse Concert-Phantasie über spanische Weisen

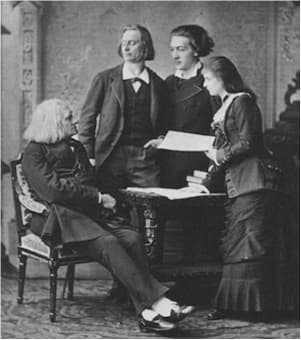

Johanna Wenzel and Jules Zerembski with Liszt

Johanna Wenzel (1857-1928) initially studied at the New Academy of Music in Berlin under Theodor Kullak. But from 1872 she regularly attended the musical evenings of Franz Liszt in Weimar, and by 1874 she had followed Liszt to Rome to become his student. According to an anecdote, Johanna once asked Liszt about surgery to cut the webbing of her fingers to increase reach. Apparently Liszt responded, “I earnestly beg of you to think no more of having the barbarous operation. Better to play every octave and chord wrong throughout your life than to commit such a mad attack upon your hands.” Luckily Johanna did not follow through with the operation as it certainly aided her swimming career. During an international swimming competition in Brussels in 1884, she won first prize. While in Rome, she also met her future husband, the composer and pianist Jules Zerembski, and they gave numerous concerts as a piano duo. Both stayed in touch with Liszt, and at a musical celebration of Liszt’s 70th birthday in Brussels, they performed the Concerto Pathétique for two pianos.

Franz Liszt: Concerto Pathétique

Richard Wagner at Bayreuth

When Franz Liszt met Richard Wagner in Paris for the first time in the spring 1840, they had little admiration for each other. Wagner, two years younger than Liszt, was neither successful nor financially secure. In fact, Wagner was actively looking for financial support from Liszt, asking him to become the publisher of his works. Liszt settled in Weimar in 1848, and he eventually staged several great Wagner festivals attracting national attention. In the event, Wagner participated in the failed Dresden Uprising and had to flee with a price on his head. He made his way to Liszt who sheltered him, arranged a loan of money and a forged passport to get Wagner out of Germany. For the next ten years Liszt supported Wagner in Swiss exile with money, gifts, and personal visits. Although Wagner was fulsome in his praise of Liszt, the relationship ran into trouble because of Wagner’s constant demand for money. Even more damaging was the fact that Liszt’s daughter Cosima left her husband Hans von Bülow to live with Wagner. Liszt personally traveled to Lucerne to confront Wagner with the result that they did not speak to each other for five years. And Liszt would never forgive his daughter for marrying Wagner in 1870, and for turning Protestant shortly thereafter.

Franz Liszt: Tristan, “Isoldes Liebestod” (Idil Biret, piano)

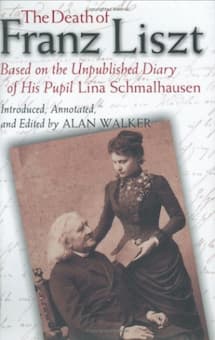

Attended by incompetent doctors and treated coldly by his daughter, Liszt “endured needless pain and indignity,” according to his student, caregiver, and close companion Lina Schmalhausen. Schmalhausen meticulously recorded Liszt’s last ten days in her diary, and when Cosima barred her from the premises, she observed Liszt on his deathbed while hiding behind bushes in the garden. Although Cosima insisted that her father’s dying word was “Tristan,” the last thing that Lina heard him say was “Please continue sleeping.” Lina had attended the first Liszt master class in Weimar in 1879, and was subsequently described as “a splendid virtuoso of masculine power and energy of design, great trait and sculptural modeling of the unusually full and large Liszt concert tone, which, however, transforms into the most fragrant pianissimo.” The relationship between Franz Liszt and Schmalhausen was always a heartfelt one, and he wrote her friendly and jocular letters. He also dedicated the “Mephisto Polka” to Schmalhausen in 1883, which included a virtuosic ossia part for the right hand throughout.

Attended by incompetent doctors and treated coldly by his daughter, Liszt “endured needless pain and indignity,” according to his student, caregiver, and close companion Lina Schmalhausen. Schmalhausen meticulously recorded Liszt’s last ten days in her diary, and when Cosima barred her from the premises, she observed Liszt on his deathbed while hiding behind bushes in the garden. Although Cosima insisted that her father’s dying word was “Tristan,” the last thing that Lina heard him say was “Please continue sleeping.” Lina had attended the first Liszt master class in Weimar in 1879, and was subsequently described as “a splendid virtuoso of masculine power and energy of design, great trait and sculptural modeling of the unusually full and large Liszt concert tone, which, however, transforms into the most fragrant pianissimo.” The relationship between Franz Liszt and Schmalhausen was always a heartfelt one, and he wrote her friendly and jocular letters. He also dedicated the “Mephisto Polka” to Schmalhausen in 1883, which included a virtuosic ossia part for the right hand throughout.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: Mephisto Polka (Sviatoslav Richter, piano)

There was another woman whom Liszt loved. She inspired him to write “Consolation” and spiritually influenced him in later years.