Very recently, I attended a recital by a rather well known pianist. After the programme proper had concluded, it was time for the encore ritual. Audience members were clapping furiously, cheering, standing up from their seats, and demanding that the performer play an extra piece or three. Shouts of “bravo,” “encore,” and “Zugabe” brought the artist back to the stage and everybody waited in hushed anticipation. The artist did announce the upcoming selection, but it was spoken in such a low voice and who knows in what language, so nobody really understood. As the first notes sounded, people started looking at each other in trying to guess the piece.

Luckily, somebody in the upper balcony whispered the name of the piece loud enough so that the entire hall could hear it. The encore that evening was the Prokofiev “Toccata,” an extremely difficult showpiece that has been popular with many virtuoso pianists. So I did a little research and found out that many famous pianists select highly challenging transcriptions of famous melodies for their encore performances. This clearly has two advantages. First, audiences can marvel at the pianistic pyrotechnics, and secondly, they immediately became part of the performance by instantly recognizing the underlying tune. It’s brilliant, really, as audiences of all kinds really want to hear what they already know.

“Flight of the Bumble-Bee” piano transcription by György Cziffra

Let’s get started with a transcription of the instantly recognizable musical hit “Flight of the Bumble-Bee,” performed by the incomparable Yuja Wang.

Yuja Wang Plays the “Flight of the Bumble-Bee,” (arr. György Cziffra)

Everybody in the classical music universe knows the brilliant and exceptional Yuja Wang, and her “Bumble-Bee” performance simply takes your breath away. Her performance doesn’t just sound like a gentle bumblebee but more like a marauding swarm of hornets. Is there anything technically she can’t do? The tune comes from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan. The opera has all but disappeared, but the “Bumble-bee” is one of the most familiar classical works because of its frequent use in popular culture. It has been arranged and transcribed for an incredible variety of performing media, and the features “Bumble-Bee” arrangement originated with the Hungarian-French virtuosos György Cziffra (1921-1994).

György Cziffra

Cziffra had bewildering skills of improvisation and technical brilliance at the piano. In fact, he became legendary as a peerless improviser, and his fiery and breathtaking extemporizations astonished audiences around the world. As he wrote, “throughout my whole youth I have been enthralled by improvisational art… When I improvise I feel as if I become one with myself, and my body is freed from all earthly pain. It is truly a process of going beyond my own talents, which makes it possible at each occasion to step over the known boundaries of the technical side of piano performance.” Cziffra was hoping that his transcriptions would open the door to new possibilities and encourage a less stereotypical and more personal approach to performances of classical piano music. I don’t know about you, but Yuja’s performance is anything but stereotypical. It certainly is highly personal, and her blazingly fast approach is mind-boggling.

Marc-André Hamelin Plays “Minute Waltz” (arr. Hamelin)

Here is the quiz question for today. What do Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji, Rafael Joseffy, Max Reger, Leopold Godowsky, Jeannot Heinen, Morris Rosenthal, Giuseppe Ferrata, Sam Raphling, Marc-André Hamelin, and Bertold Hummel have in common? They all fashioned virtuoso transcriptions of Chopin’s “Minute Waltz.” At some point it might be fun to compare these different versions, but just the number of pianists/composers who worked on this melody gives testament to the popularity of the Chopin tune. The popular nickname “Minute Waltz” is misleading, as it is not intended to be played in one minute. Rather, the publisher meant to indicate a “miniature” waltz, in the sense of a little waltz. Of course, in France it is known as “Petit Chien” or puppy. Nicknames aside, the tune entered popular culture in such movies as “Pretty Little Liars,” “The Girlfriend Experience,” “On Tree Hill,” and “Sex and the City.”

Marc-André Hamelin

I really do like the transcription by Marc-André Hamelin, a pianist who has been called “a performer of near-superhuman technical prowess.” He is considered one of the marvels of the twenty-first century, “as few living pianists can match his transparency of articulation, rhythmic and tonal control and cunning virtuoso strength.” While his performances are notable for their mastery of the most outlandish difficulties, Hamelin is also a talented composer and arranger. “He has written works which take virtuoso pianism to its limit, and you can hear it in his arrangement of the “Minute Waltz.” It’s genius, really, as it starts out as a beautiful and very sensitive rendition of the original Chopin waltz. But wait, Hamelin has a surprise waiting for you. In a pun on the nickname “Minute Waltz,” he then performs the piece in “Seconds,” intervals that is. Maybe I am just easily amused, but I think it’s hilariously funny.

Vladimir Horowitz Plays “Variation on a theme from Carmen” (arr. Horowitz)

Vladimir Horowitz (1903-1989) would drive audiences wild with his transcriptions of “The Stars and Stripes Forever,” and his “Carmen Variations.” In fact, Horowitz was generally not allowed to leave the stage before he had played one of them. Today we consider him one of the greatest pianists of all time, known for his virtuoso technique, tone color, thundering octaves, and “the public excitement he created by his performances.” However, it is well known that he always wanted to become a composer. Even after one of the most successful careers as a pianist in history, he felt “frustrated that he had not dedicated more of his life to composing.” All of his surviving original compositions date from his student years in Russia, but his later paraphrases and variations of famous melodies drove audiences into a state of ecstasy.

Vladimir Horowitz

The “Carmen Variations” are based on the “Gypsy Dance”, a melody every music lover knows by heart, from Act II of Bizet’s opera Carmen. That energetic melody has been the source of a substantial number of virtuoso elaborations. Horowitz played his “Variations” from his earliest concerts in the 1920s all the way through his golden jubilee in 1978, over 50 years later. In fact, Horowitz was very protective of his “Carmen Variations,” as he did not want them to be published. We know that he showed the score to some friends and acquaintances, and he even made a piano roll of the piece, but the score stayed with him. While Horowitz was showing off his pianistic powers and technique, it is very interesting that the piece changed over time. A commentator wrote, “it is almost strictly a virtuoso showpiece, but as the years progressed, the variations became more sophisticated.” I read that there are at least five main versions of the Horowitz “Carmen Variations,” but he eventually got tired of the hype surrounding the work. As he once remarked, “after hearing the encore, everybody forgot the rest of the programme.”

Mikhail Pletnev Plays “Blue Danube Waltz” (arr. Schulz-Evler)

Do you know the name Adolph Schulz-Evler (1852–1905)? To my shame, I must confess that I had never heard of him before I started this blog. In the event, he was a pianist of Polish origin who first studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then went to Germany for lessons with the famed piano virtuoso, composer, and arranger Carl Tausig. Schulz-Evler taught at the Kharkiv Conservatory for two decades, and he “probably composed around 52 works, most of them forgotten today.” However, he did write himself into the pages of music history with one very famous work, his paraphrase on the “Beautiful Blue Danube” by Johann Strauss Junior. The original series of waltzes enjoyed unprecedented popularity, and pianists from all over the world wanted to share in its reflective glory. As such, Schulz-Evler reshaped the orchestral composition into a glorious piano transcription of extreme virtuosity that reflected the elegance and sophistication of turn-of-the-century Vienna. First published in 1900, it was received to great acclaim, and many renowned pianists have produced recordings since.

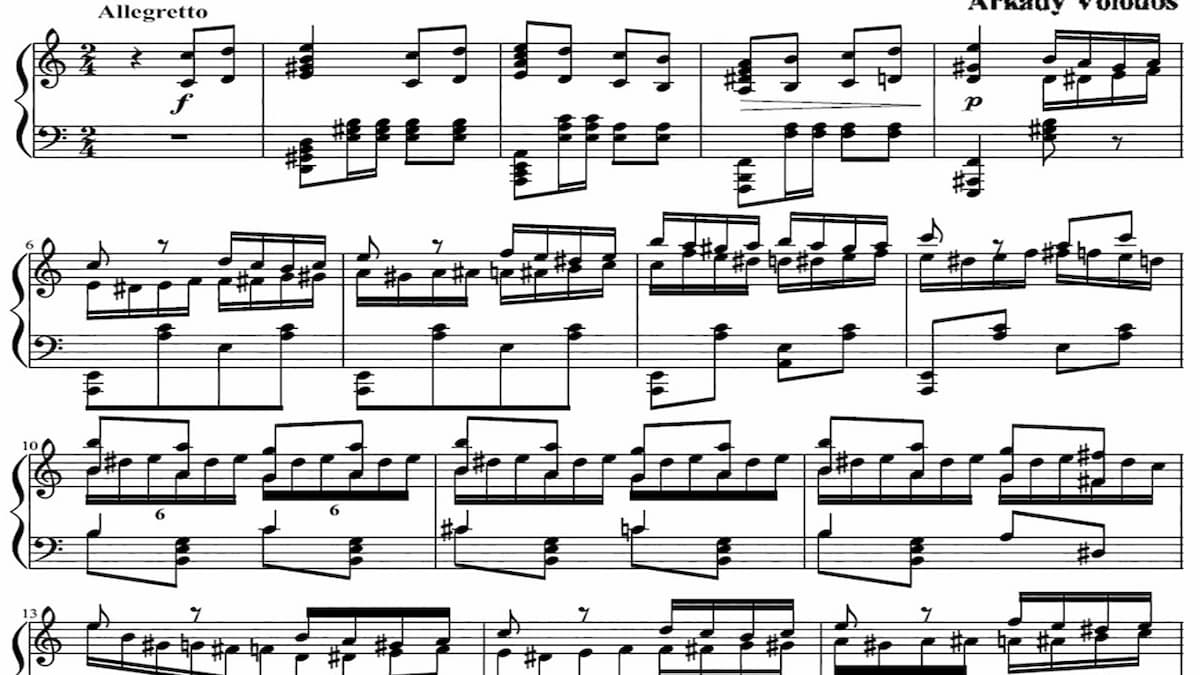

Mozart’s “Turkish March” piano transcription by Arcadi Volodos

The third movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 11 in A major, K. 331 is titled “Rondo all Turca,” or “Turkish March.” I am not absolutely sure, but this might be one of Mozart’s best-known piano pieces. Certainly everybody who ever took rudimentary piano lessons will have tried to play that piece. The tune was already famous in the 19th century when Max Reger composed an orchestral work consisting of nine variations and a fugue based on the opening theme. During the golden age of pianism, transcriptions, arrangements, and paraphrases were plentiful, but they gradually disappeared from view. Only very recently have they began to make a comeback, and when we listen to Arcadi Volodos’ take on the “Turkish March” we can definitely say that these kind of creative exercises are back with a bang. In the words of pianist Earl Wild, “As long as there are creative musicians who can improvise and imagine background and settings, the art of transcription will remain timeless.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Arcadi Volodos Plays “Turkish March” (arr. Volodos)