We know the ‘barcarolle’ most famously from Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann, but relatively few other composers picked up on it. In Offenbach’s opera, the barcarolle, ‘Belle nuit, ô nuit d’amour’ (Beautiful night, oh night of love) opens Act III where our luckless hero Hoffmann falls in love with Giulietta, who, unfortunately for Hoffmann, has other plans. Other opera composers such as Paisiello, Weber, and Rossini included the style in some of their arias, and both Donizetti and Verdi used it in their operas.

The barcarolle was a traditional boat song of the Venetian gondoliers – its characteristics are a rhythm copying the gondolier’s stroke in the water and a moderate 6/8 time.

Venetian Gondolier

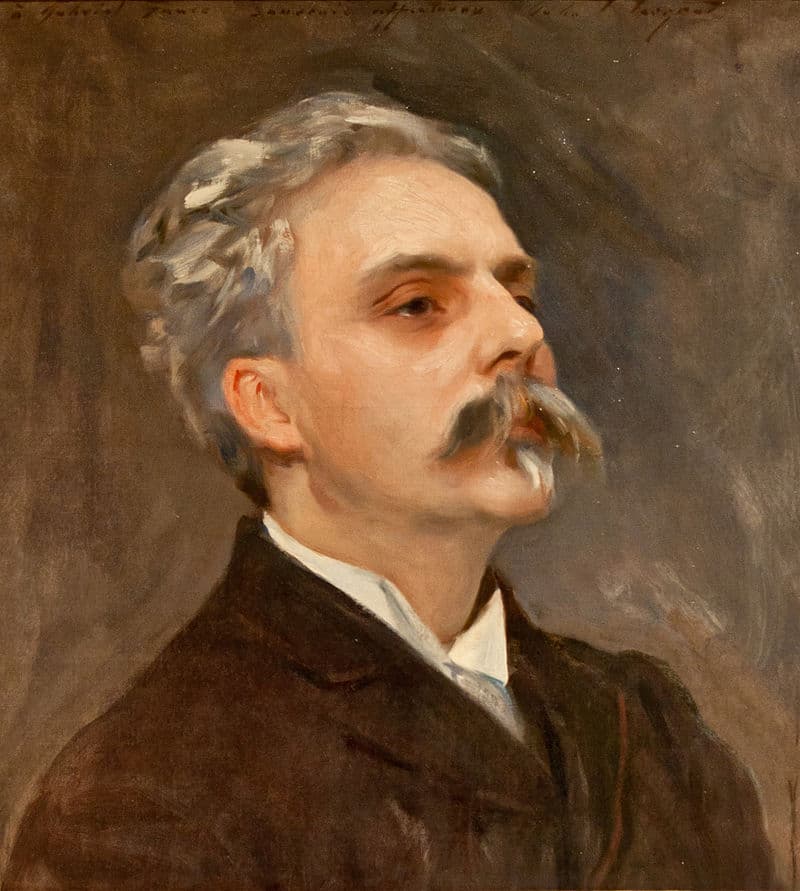

Other composers took up the form, but rarely: Chopin wrote one, and Mendelssohn wrote three as part of his Songs Without Words collections. It was Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924) who took up the barcarolle and wrote 13 of them, having taken, it is assumed, the idea from Chopin. These barcarolles, along with his nocturnes, are considered some of Fauré’s greatest works.

John Singer Sargent: Gabriel Fauré, 1896

Fauré used the title of barcarolle but didn’t adhere religiously to the form. One important thing to note about Fauré was that he was ambidextrous – could use both right and left hands equally well – and this comes through in the barcarolles. In more than one piece, the melody is in the middle register, with the high and low registers being used for accompaniment of the central melody. One writer compared this to a mirror image on the water where the major image is in the middle, with reflections at the top and bottom.

Fauré wrote his first barcarolle in 1880 and his last one 41 years later, in 1921. Across all of the barcarolles, we can see the development of Fauré as a composer, from the uncomplicated early ones, the lyricism and complexity he achieved in the 1890s (barcarolle no. 5), and the enigmatic essence of his final ones.

Barcarolle No. 1, 1880, was given its premiere by Camille Saint-Saëns in 1882. It has the 6/8 time and the rocking feeling we expect, as well as a ‘conventional sweetness,’ but the minor key throws a little shadow on the work.

Gabriel Fauré: Barcarolle No. 1 in A Minor, Op. 26 (Marc-André Hamelin, piano)

In 1894, after a gap of five years when Fauré wrote no piano music, Barcarolle No. 5 emerged. Dedicated to Mme la Baronne V. d’Indy, Isabelle de Pampelonne, wife of the composer Vincent d’Indy, the work is in a more powerful style. There are no internal sections in the work, divisions are made by changes in time signature.

Gabriel Fauré: Barcarolle No. 5 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 66 (Marc-André Hamelin, piano)

The cheerful theme that opens Barcarolle No. 8 of 1906 is turned relatively quickly to melancholy. This is one of Fauré’s rare excursions into whole-tone writing.

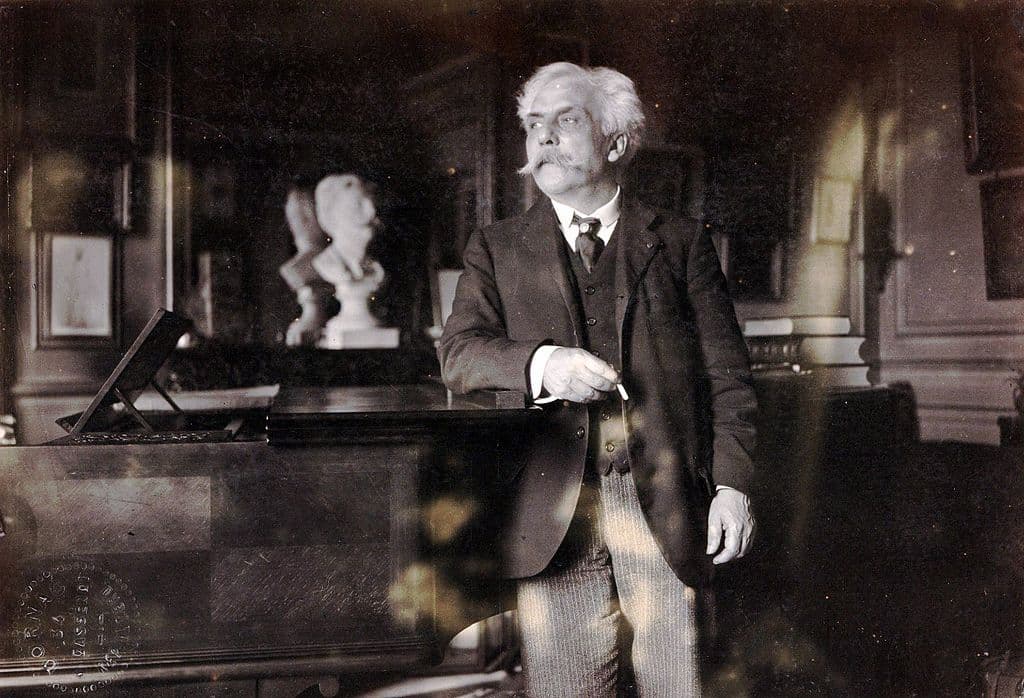

Dornac: Fauré, next to the piano in his flat in the boulevard Malesherbes, Paris, 1905

Gabriel Fauré: Barcarolle No. 8 in D-Flat Major, Op. 96 (Marc-André Hamelin, piano)

Fauré’s final Barcarolle was written at the same time as his second piano quintet and his second cello sonata. It seems to share with them a certain dryness that, at the same time, feels deeply nostalgic. It’s as though he’s trying to return to the ideas of his first Barcarolles but with so much more knowledge that it’s sentimental rather than innocent.

Gabriel Fauré: Barcarolle No. 13 in C Major, Op. 116 (Marc-André Hamelin, piano)

These are no longer the boat songs of the working Venetian gondolier but complex and evocative works that often have complex harmonies and subtle rhythms. By making the Barcarolle his own, Fauré was able to imbue it with more than just being work songs. He could make the music reflect the water world of Venice, with the mirroring of the waters made part of the structure of the music.

After Fauré, other composers took up the Barcarolle, including Belá Bartók, Edward MacDowell, Ned Rorem, and Leonard Bernstein (in Candide), but no one used it throughout his complete career as Fauré did.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter