The “opera fantastique” The Tales of Hoffmann (Les Contes d’Hoffmann) by Jacques Offenbach was first played publically, without the third act, at the Opéra-Comique in Paris on 10 February 1881. The composer did not live to see the premiere, as he had died just four months before the opening on 5 October 1880. Shortly before his death, he wrote to the impresario and stage director Léon Carvalho, “Hurry up and stage my opera. I have not much time left, and my only wish is to attend the opening night.”

The Incomplete Music Score

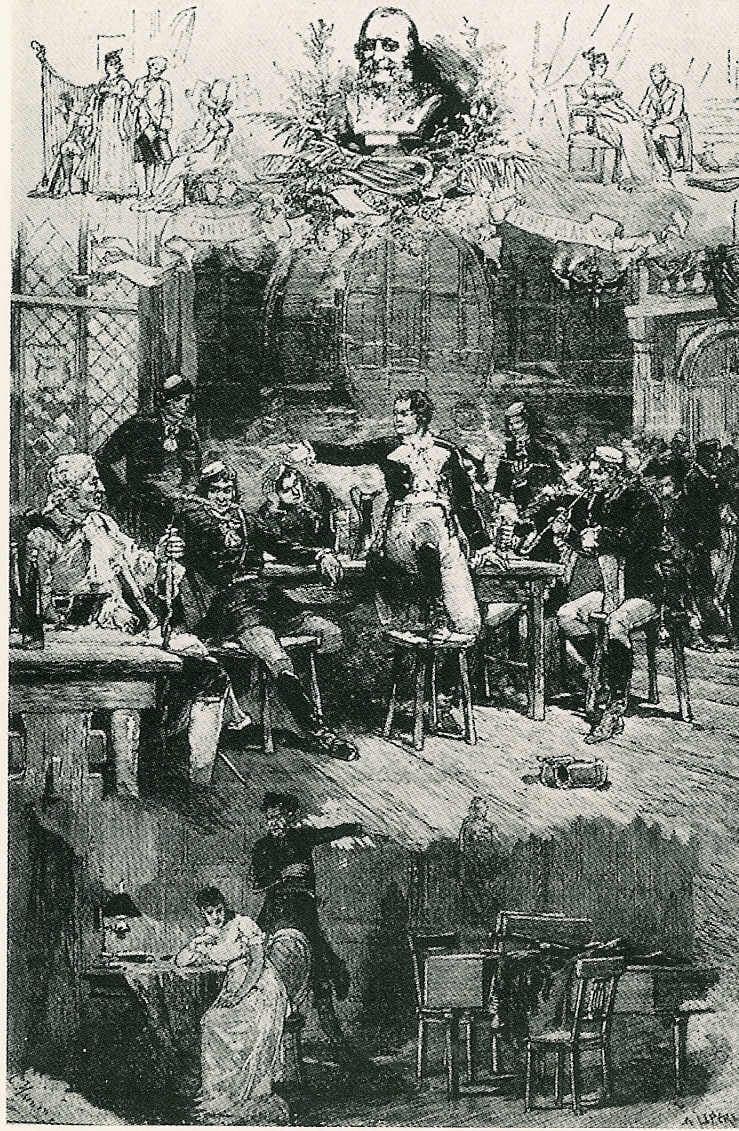

Illustration from the 1881 première of Jacques Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann, showing the prologue

Although Offenbach had completed substantial portions of the piano score and orchestrated the prologue and first act, it was left to Offenbach’s son Auguste, with help from Ernest Guiraud, to initially complete the work. The four-act version with recitatives first played at the Ring Theater in Vienna on 7 December 1881. The luxurious and ornate theater hosted the most popular performances of the day, and it was filled to capacity on 8 December for the second performance when disaster struck.

Jacques Offenbach: The Tales of Hoffmann, “Tu ne chanteras plus?”

The Disaster at the Second Performance

Les Contes d’Hoffmann Parisian Premiere

Shortly before the performance was to start, a stagehand took a long-arm igniter to light the row of gaslights above the stage. Inadvertently he also lit some prop clouds that were hanging over the stage. As the flames quickly took hold of the stage curtain, general confusion ensued. The iron fire curtain was not lowered, and the available water hoses were not utilized. Even worse, the stage manager panicked and shut off the gas, plunging the theater into complete darkness. People attempted to flee in panic, but the exits became jammed. The fire brigade brought ladders that were too short to reach even the first balcony, and people started jumping. They not only killed themselves but also crushed people on the ground floor. Safety nets finally arrived and allowed people to jump from the balconies, but the estimated death toll was somewhere between 620 and 850 people. “The Royal Family of Austria arrived at the theater as the disaster was ending and immediately began collecting relief funds for the victims and their families. Crown Prince Rudolf was particularly emotional, crying upon seeing the hundreds of lifeless bodies.”

Jacques Offenbach: The Tales of Hoffmann, “Il était une fois à la cour d’Eisenach”

Richard Wagner’s Response to the Disaster

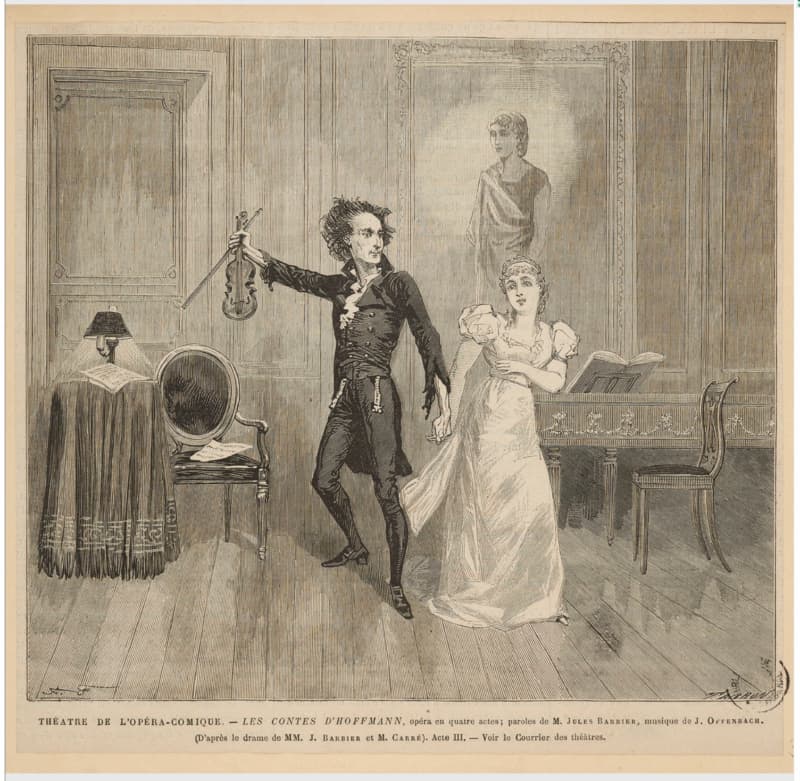

Illustration from the 1881 première of Jacques Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann, showing the Olympia act

Always the humanitarian, Richard Wagner said of the Vienna fire, “People are too wicked for one to be much affected when they perish in masses…. When such-and-such a number of them die while watching an Offenbach operetta, an activity which contains no trace of moral superiority, that leaves me quite indifferent.” As you can tell, Wagner was no friend of people and he certainly hated Offenbach. In response to the spectacular failure of Tannhäuser at the Paris Opera in 1861, Offenbach mercilessly satirized Wagner in a droll sketch called Le musician de l’avenir. It contains a caricature of a “Musician of the Future,” who proclaims egotistically, “Here I am! Here I am! I am a Revolution in myself alone.” Wagner never forgave Offenbach, and by the early 1870s he simply referred to Offenbach as “filth.” As a recent publication details, “Wagner attacked his fellow composer both publicly and privately and sought to establish a polarity between the two, confining Offenbach to the realm of frivolous and materialistic popular folk culture while casting his own work as exemplary of the new German spirit.” Offenbach was rather resistant to Wagner’s attacks, and he declared forthrightly, “To be erudite and boring isn’t art; it’s better to be pungent and tuneful.”

Jacques Offenbach: The Tales of Hoffmann, “Les Oiseaux dans la Charmille”

Critics and Public Reception

Les contes d’Hoffmann, Antonia act, showing Antonia and Dr. Miracle

The association of The Tales of Hoffmann with the horrific fire in Vienna gave the work a reputation for bad luck that slowed its international acceptance. Only after a spectacular production in Berlin in 1905, with added musical numbers written neither by Offenbach nor by Guiraud, did it establish its international popularity. What makes Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann unique is “that it is the one enduring serious opera composed by a man who earned his reputation, and his lasting place in social and music history, by writing 105 decidedly non-serious works.”

Illustration from the 1881 première of Jacques Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann, showing the Giulietta act

As a result of Offenbach’s untimely death, however, even favorable critics tend to describe the work as “problematic,” “potential,” or “unresolved” masterpiece. Offenbach’s death left producers with a text that cries out for reconstructive surgery. For decades, producers had taken the libretto and stage directions literally, but lately, “the three love stories have been depicted in more psycho-dramatic ways.” The Tales of Hoffmann will almost certainly undergo additional revisions and rivaling publications, but Offenbach’s technique and popular touch have combined to provide a work of endless fascination to audiences.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Jacques Offenbach: The Tales of Hoffmann, “Belle Nuit”