Many pieces of classical music are famous for their massive scale. Maybe that’s why so many composers have written classical music about the vast expanse of outer space.

Today, we’re looking at fifteen pieces of classical music inspired by other planets and galaxies.

Get ready for takeoff!

© indietips.com

Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes by Heinrich Schütz (1648)

Heinrich Schütz was a great seventeenth-century German composer.

In 1648, he set Psalm 19, which in English begins with the sentence, “The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands.”

The psalm goes on to describe how the presence of the stars is a constant silent reminder of the existence of God.

The motet that Schütz composed has a vivacious awe to it. This is a celebration of the glory of outer space.

Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes from The Creation by Joseph Haydn (1798)

The Creation tells the story of the creation of the world as described in the Biblical book of Genesis.

Toward the end of the oratorio, Haydn’s singers quote the nineteenth psalm, marveling at its message of God’s power and creativity.

This music paints a genteel portrait of a delightfully ordered cosmos, with every planet in perfect alignment.

Music of the Spheres by Josef Strauss (1868)

The Strauss family wasn’t just a family; they were a veritable dance-music dynasty.

Josef Strauss was the younger brother of Johann Strauss II, and they were both the sons of Johann Strauss the elder. All three men were composers.

Johann the younger, who is the most famous of the three, composed On the Beautiful Blue Danube. He once said about Josef, “He is the more gifted of us two; I am merely the more popular.”

The Music of the Spheres waltz opens with gentle swells and pizzicato strings that feel like floating up into the sky and beyond. Two minutes in, the romantic dance begins in earnest.

The Planets by Gustav Holst (1914-17)

Ask a musician to name a piece of classical music inspired by space, and they’ll almost certainly answer The Planets by Gustav Holst.

From the terrifying warlike character of the opening Mars movement to the scurrying excitement and serene nobility of the Jupiter movement, this orchestral suite based on the planets has secured a reputation as a perpetual crowd-pleaser.

The work is seven movements long, one for each planet in our solar system.

As Três Marias by Hector Villa-Lobos (1939)

These three sparkling piano miniatures portray “the Three Marys”, the three stars of Orion’s belt.

These stars are also known as Alnilam, Alnitak and Mintaka.

As Três Marias proved to be among composer Hector Villa-Lobos’s most popular piano works.

Die Harmonie der Welt by Paul Hindemith (1957)

Translated from German, Die Harmonie der Welt means “The Harmony of the World.” It’s the name of a five-act opera by German composer Paul Hindemith.

The opera is inspired by the life and work of German astronomer, philosopher, and music writer Johannes Kepler, who lived from 1571 to 1630.

Johannes Kepler

When he was around thirty years old, Kepler began writing what became The Harmony of the World. In this famous work, he tried to link musical consonance with the motion of planets.

Hindemith was so inspired by this history that he wrote a symphony inspired by it in 1951. In 1957 he returned to the subject matter for an opera.

Symphony No 48 by Alan Hovhaness (1981)

Alan Hovhaness was an extremely prolific composer of both American and Armenian origin. He was extremely long-lived, too, only dying in 2000 at the age of eighty-nine.

Over the course of his life, he completed sixty-seven symphonies. This is his forty-eighth, subtitled Vision of Andromeda.

It was composed in 1981 and premiered by the Minnesota Orchestra. Conductor Leonard Slatkin apparently strongly disliked it, didn’t want to rehearse it, and left the musicians to sight-read it at its premiere, where, fortunately, it was positively received by the audience.

Hohvannes.com describes the symphony as having “big-boned unisonal themes in strings and brass, solo woodwinds floating above pizzicato strings, gamelan-like percussion, timpani ostinati and fugal expositions.”

Spiral Galaxy from Makrokosmos, Volume 1 by George Crumb (1972)

Over the course of his life, composer Béla Bartók wrote a series of piano pieces he called Mikrokosmos. Composer George Crumb was later inspired to write his own set of piano pieces, tweaking the title to Makrokosmos in homage.

The first volume is subtitled “Twelve Fantasy-Pieces after the Zodiac.” It contains twelve pieces, one for each zodiac sign.

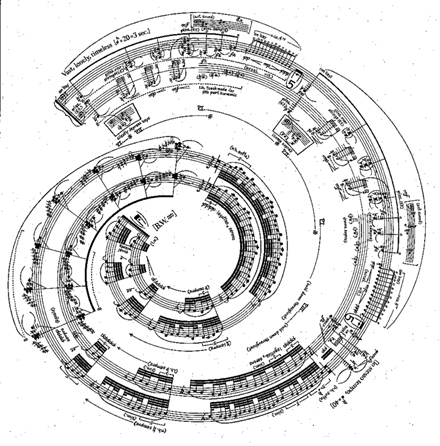

George Crumb: Makrokosmos – Spiral Galaxy

The twelfth piece is named “Spiral Galaxy [SYMBOL] (Aquarius).” The score is written in a spiral shape.

Timbres, espace, mouvement by Henri Dutilleux (1978)

Timbres, espace, mouvement translated into English means “Timbre, space, movement.” It is subtitled La nuit étoilée, or “The starry night”, in reference to Vincent van Gogh’s famous painting, “Starry Night.”

Dutilleux’s goal was to portray the “almost cosmic whirling effect which (the painting) produces.”

One way he sought to do this was by removing violins and violas from the work’s instrumentation. He wanted the work to have a bass-heavy presence to imitate the dark earthbound shapes in the lower half of the painting.

A la busca del más allá (In search of the beyond) by Joaquín Rodrigo (1978)

In 1970, composer Joaquín Rodrigo went to the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Because Rodrigo was blind and couldn’t see the moon rocks on display, he was allowed to touch them.

The experience had a profound impact on him. When he was asked in 1976 to compose a piece in honor of America’s bicentennial, he thought back to that Johnson Space Center visit.

The result was this symphonic poem, A la busca de más allá, or “In search of the beyond.”

According to Rodrigo, the piece contains “no definite story or descriptive content.” However, the cymbal rolls that open and close the piece were intended “to evoke in the listener the sense of mystery associated with the far-off, the ‘beyond.’”

Airs from Another Planet by Judith Weir (1986)

In this 1986 work, Judith Weir posits an interesting question: what might happen to the musical culture of human colonizers on Mars?

Weir was inspired by the idea that future residents of Mars might first undergo training by living on a harsh, inhospitable Scottish island, and that they might then bring elements of Scottish music into space with them.

“This is the music of the Scottish colonisers, several generations later,” Weir writes about Airs From Another Planet, “marooned on a lonely and distant planet; the ancient forms of their national music almost completely lost in translation, with only the smallest vestiges of the national style remaining.”

Musica Celestis by Aaron Jay Kernis (1990)

Composer Aaron Jay Kernis’s own program note for this piece reads, in part, “Musica Celestis is inspired by the medieval conception of that phrase which refers to the singing of the angels in heaven in praise of God without end…I don’t particularly believe in angels, but found this to be a potent image that has been reinforced by listening to a good deal of medieval music.”

The spaciousness of this music calls to mind unfathomably vast vistas and unexplored horizons.

Sun Rings by Terry Riley (2002)

In 2000 the NASA Art Program invited the renowned Kronos Quartet to use sounds that had been recorded on spacecraft and incorporate them into a musical project.

American composer Terry Riley, known for his work in the minimalist style, wrote music for that project, which became known as Sun Rings.

In addition to music for string quartet, Riley included parts for chorus.

Sun Rings ended up being ten movements long!

Asteroid 4179: Toutatis by Kaija Saariaho (2005)

Asteroid 4179, also known as Toutatis, is the asteroid whose orbit passes closest to Earth.

Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho found herself inspired by the object’s shape and rotational pattern. She wrote in program notes for the piece:

“When reading more and then seeing pictures of it, I started to find its unusual shape and complex rotation interesting — different areas of it rotate at different speeds. One consequence of this is that Toutatis does not have a fixed north pole like the Earth; instead, its north pole wanders along a curved path roughly every 5.4 days. The stars viewed from Toutatis wouldn’t repeatedly follow circular paths, but would crisscross the sky, never following the same path twice. So Toutatis doesn’t have anything you could call a ‘day.’”

Deep Field by Eric Whitacre (2015)

Deep Field is a 23-minute work for orchestra, chorus, and, intriguingly, smartphone app.

Before a performance, audience members are asked to download an app. The app will play electronica sounds around the auditorium, creating an immersive surround-sound experience.

Whitacre has always been fascinated by space. Deep Field traces its inspiration back to the Hubble Deep Field, which is a collection of 350 exposures taken over ten days that reveal more than 3,500 galaxies.

We wrote about Deep Field here after one of our contributors went to a performance.

Conclusion

For centuries, composers have written classical music about outer space, the heavens, the spheres, asteroids, galaxies, stars, and more. We hope you’ve enjoyed this musical survey of the cosmos!

What’s your favorite classical music about outer space?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter