In November 1918, Arnold Schoenberg founded the Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen (the Society for Private Musical Performances) as a way for his pupils and others to get to know modern music. Although this was Schoenberg’s idea, it was really organized by his students, and the prospectus was written by Alban Berg in 1919. It’s an interesting document that, in its quiet way, outlines the problem with so many modern music concerts. The Society’s conditions were quite stringent:

that performances must be high quality and thus well-rehearsed; that works should be repeated so that listeners could have several opportunities to hear something new; and that the whole procedure should be carried out without the ‘corrupting influence of publicity’. There were no public advertisements or reviews of concerts, and audience members were not allowed to show any signs of approval or disapproval during a performance (no clapping or booing!) – the programmes were not even announced in advance, so that preconceptions associated with certain composers or work types could not influence a member’s decision to attend or avoid an event.

Arnold Schoenberg, ca. 1930

These same problems afflict modern music concerts even a century later: they tend to be one-offs, so you can’t hear the music enough to be familiar with it; publicity tends to push the well-known ahead of the little-known; and concerts are prejudged just on work titles alone.

Alban Berg, 1920s

What was considered ‘modern’ music? Berg wrote to his wife saying it would be ‘Mahler to the present’, given once a week. And so, over the three years of the Verein, over 100 concerts were given, with music by Bartók, Berg, Busoni, Debussy, Ravel, Reger, Schoenberg, Scriabin, Stravinsky, Szymanowski, Webern, Wellesz, Zemlinksy and Gustav Mahler, among many others.

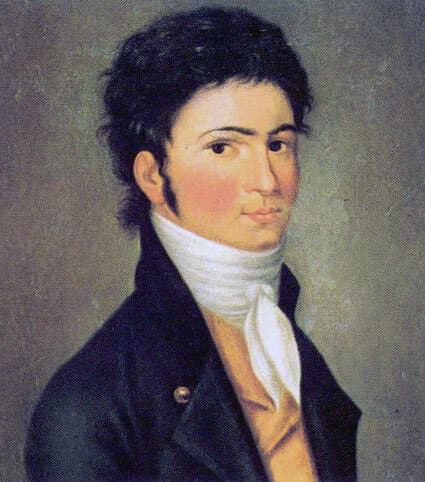

Arnold Schoenberg, 1911 (note pictures of Mahler over his desk)

As always, there were practical considerations. Large-scale works could not be performed, so symphonies were out. However, since the series was being put on by competent composers, the works could be played in other formats: reduced for piano duet or piano four-hand, arranged for chamber orchestra, and so on. The basic ensemble available was piano, harmonium, flute, clarinet, and string quartet, with other players added when possible.

Gustav Mahler wrote his Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) in 1884–1885. This collection of four songs was completed in 1885 and then revised. The original piano accompaniment was made into an orchestral accompaniment in the early 1890s. The texts are by Mahler, and were heavily influenced by the folk poetry of Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn), which had been collected and edited by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano, and published in 1805 with two more volumes in 1808. The collection was a favourite of Mahler’s and he set it to music throughout his composing career.

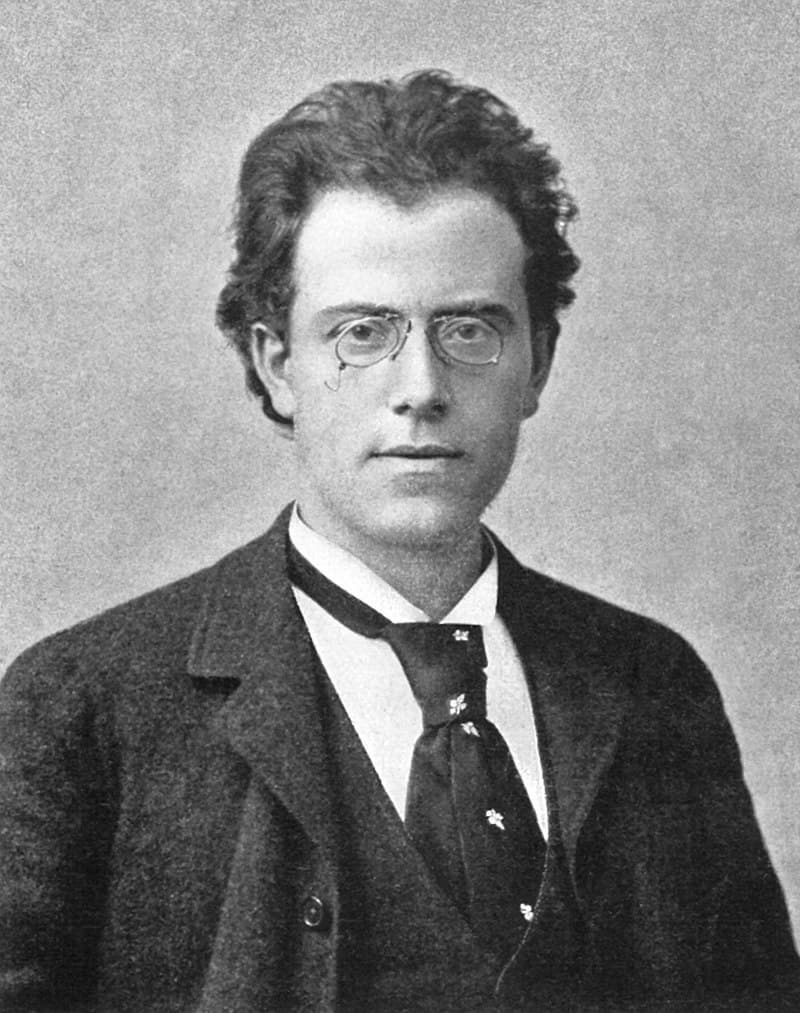

Gustav Mahler, 1892

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen reflected Mahler’s unhappy love affair with soprano Johanna Richter. His love poems were the basis for this collection.

Johanna RIchter, 1894

The first song, Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht (When My Sweetheart is Married) makes a parallel between his love’s happiest day and his own day of mourning and sorrow.

Gustav Mahler: Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) (arr. A. Schoenberg for voice and ensemble) – No. 1. Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht (When My Sweetheart is Married) (Roderick Williams, baritone; Attacca Quartet; Virginia Arts Festival Chamber Players; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)

The second song sounds like he’s recovered his good humour: he’s walking across the fields, greeting the birds, rejoicing in the flowers, and everything bright and glittering in the sunshine…except for him. His happiness is closed in its buds, never to bloom again. This ‘everyone is happy except me’ can be traced back to Petrarch’s poetry about his love for the unattainable Beatrice.

Gustav Mahler: Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) (arr. A. Schoenberg for voice and ensemble) – No. 2. Ging heut’ Morgen übers Feld (I Went This Morning Over the Field) (Roderick Williams, baritone; Attacca Quartet; Virginia Arts Festival Chamber Players; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)

Things get bad in the third movement – he feels as though he’s constantly being cut in his heart with a red-hot knife. He sees her everywhere – her blue eyes in the sky, her blonde hair in the yellow fields, and the sparkle of her laughter around him everywhere, as he imagines as he lies on his death bed…. The setting is dramatic and self-indulgent. She cannot help what he imagines and he torments himself.

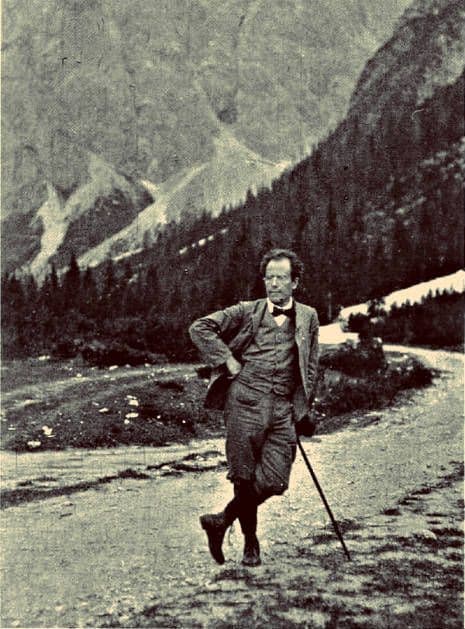

Mahler hiking

Gustav Mahler: Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) (arr. A. Schoenberg for voice and ensemble) – No. 3. Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer (I Have a Gleaming Knife) (Roderick Williams, baritone; Attacca Quartet; Virginia Arts Festival Chamber Players; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)

Some normalcy returns in the last song – just like Schubert’s unnamed lost lover of Winterreise, he has been sent off to the wide world, walking out in the dark across the heath with no one to bid him farewell. He falls asleep under a linden tree and under the fall of its snowy blossoms (like the snow of Winterreise?) he finds peace again.

Gustav Mahler: Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) (arr. A. Schoenberg for voice and ensemble) – No. 4. Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz (The Two Blue Eyes of my Beloved) (Roderick Williams, baritone; Attacca Quartet; Virginia Arts Festival Chamber Players; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)

Schoenberg did the reduction of the orchestral version for chamber orchestra, and although the reduction, isn’t as powerful as the full orchestral version, the slimmed-down texture makes the contrapuntal writing clearer. Also, the smaller orchestra means that the vocal soloist isn’t in danger of being overpowered by the instruments. Schoenberg eliminated the timpani part but kept the triangle part for the birds and flowers of the first two songs. He did maintain the separation between winds and strings and used the two keyboards to double for missing instruments. The piano replaces Mahler’s harp and some oboe lines, and the harmonium covers the additional horn parts.

Schoenberg’s version premiered at the Verein in 1920 and was conducted by Schoenberg. The song cycle is one of Mahler’s most popular and, as his first song cycle, has so much in it that presages his later writings, particularly the real use of Des Knaben Wunderhorn texts in his later works and through his ‘Wunderhorn period’ of 1887–1901.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter