I have never really played in a chamber music group, but if I had the chance, I would probably try to find a piano trio. It is not only one of the most popular ensembles in chamber music, but it is also my favourite. Normally, the piano trio consists of a group of three instruments, including the piano, the violin, and the cello, but other combinations are known as well. In this blog, I will focus on the classical ensemble because it is probably the most widely cultivated form of chamber music, second only to the string quartet. But the main reason, of course, is because some of the most beautiful chamber music has been composed for that particular grouping.

Piano Trio

Instrumental trio groupings had been popular for a while, but the piano trio arrived relatively late on the classical music stage. There is a simple explanation for that, and it all has to do with the relatively slow development of the piano. A scholar writes, “The piano trio had to wait upon the evolution of a truly efficient instrument, one with enough power to match the strings in the ensemble and sufficient mechanical capability to ensure clarity in the attack and release of notes and precise damping.” Once that was accomplished, composers began to experiment with blending and balancing the ensemble, and to find ingenious ways of distributing the thematic materials among the instruments. These experimentations resulted in a huge number of glorious piano trios composed over roughly three centuries. For me personally, piano trios are one of the crowning achievements of chamber music, and I decided to compile a list of my ten personal favourites.

Franz Schubert: Piano Trio No. 2 in E-flat Major, D929

The reason I put the Schubert E-flat trio at the top of my list is twofold. For one, Schubert completely freed the cello part from its historical role as harmonic support, and he adopted a four-movement scheme. This finally gave the work “a scale and importance previously only associated with the string quartet and the symphony.” Robert Schumann called the Schubert trio “active, masculine, and dramatic,” and it probably dates from the final year of Schubert’s life.

A Schubert Evening in a Vienna Salon by Julius Schmid

For me personally, it is a kind of paradigm of what the piano trio, or other chamber music for that matter, is all about. All three instruments perform with remarkable freedom, individuality, and assurance, but the piano is not allowed to dominate the others. It is, according to a scholar, “a genuine three-sided partnership, with Schubert achieving an artistic triple alliance.” Schubert heard the work in public in March of 1828 and he decided to shorten the last movement by almost 100 measures. For this blog, I picked a performance that reinstates the cut measures because it communicates more clearly what Schumann described as a work “that has passed across the face of the musical world like some angry portent in the sky.”

Maurice Ravel: Piano Trio in A minor

When Maurice Ravel started work on his Piano Trio in A minor in 1914, he essentially faced two problems. For one, the genre was considered too restricted in color and articulation to offer new modes of modernist expression, and it was aesthetically tied to a long romantic tradition. Essentially at that time, chamber music was considered the domain of traditionalists and conservative composers. Ravel really didn’t mind these labels, and he first established a framework of the traditional sonata concept. As he communicated to his student Maurice Delage, “I’ve written my trio. Now all I need are the themes.”

The French Grand Piano, 1781

However, in lieu of the traditional motivic development and dramatic key schemes, “he substituted eloquent phrase repetitions, extended ostinatos, contrasted tempo blocs, and a striking combination of modality and progressive tonality.” Ravel also adopts a somewhat orchestral approach to his writing, “making extensive use of the extreme ranges of each instrument, and employing coloristic effects.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Trio No. 4 in E Major, K. 542 (Beaux Arts Trio)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Trio No. 4 in E Major, K. 542

The Mozart family playing chamber music

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed six complete works for piano, violin, and cello, or what we would call piano trios. This type of chamber music was probably written for Mozart’s circle of friends as he wrote to his benefactor Michael Puchberg in 1788. “When will we meet again for a small musique? I have written a new trio,” identifying the Trio K. 542 in the postscript. This particular mature piano trio had to wait until Mozart’s discovery of the new pianos by the Viennese makers Stein and Walter. In 1777, Mozart wrote to his father, “In whatever way I touch the keys, the tone is always even. It never jars, it is never stronger or weaker or entirely absent. Stein’s instruments have this special advantage over others that they are made with an escape action.” I have always assumed that the process of composing was very easy for Mozart. However, he seems to have found it difficult to wed the sounds of the improved piano to the string instruments. I read that he produced a large number of trio sketches and left several half-finished attempts. In the end, of course, Mozart got it perfectly right and the E-major Trio K. 542 has been “described as the crowning glory of Mozart’s work in the genre.”

Anton Arensky: Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 32

Rimsky-Korsakov callously said, “in his youth, Anton Arensky did not escape some influence from me; later the influence came from Tchaikovsky. He will quickly be forgotten.” And some mean-spirited critics even called Arensky the “tiny Tchaikovsky.” What really irritated Rimsky-Korsakov and other critics was the fact that Arensky was not particularly interested in musical folklore or Russian musical identity. Instead, he combined his native musical influences with a much more cosmopolitan compositional style. One thing is for sure, Arensky had an easy gift for melody, and “some of his subtle musical nuances have been damningly described as being too pretty.” Arensky himself described his chamber music as “a dramatically self-assured music of lyrical beauty.” Arensky was 43 years old and taught at the Moscow Conservatoire when he composed his D-minor Piano Trio. That chamber music work is one of the reasons that Arensky has not been forgotten, and the famed Leo Tolstoy suggested, “among the new composers, he is the best; he is simple and melodious.”

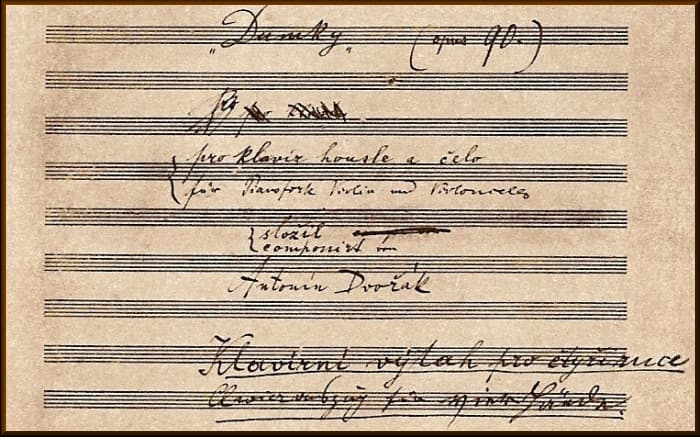

Antonín Dvořák: Piano Trio No. 4 in E minor, Op. 90 “Dumky”

In contrast to Arensky, Antonín Dvořák was very much interested to establish national identity through music. And the so-called “Dumky” Trio quickly became one of the most admired of his chamber compositions.

Manuscript of Dvořák’s “Dumky” Piano Trio

“Dumka” is a musical term introduced from the Ukrainian language and it designates an “instrumental piece characterized by vivid swings of mood and tempo, between sad and joyful, expressive of a particular Slavonic volatility of temperament.” In the Dvořák “Dumky” this results in a spontaneous structure of six movements. A critic writes, “The form of the piece is structurally simple but emotionally complicated, being an uninhibited Bohemian lament. Considered essentially formless, at least by classical standards, it is more like a six-movement dark fantasia—completely original and successful, a benchmark piece for the composer. Being completely free of the rigors of sonata form gave Dvořák license to take the movements to some dizzying, heavy, places, able to be both brooding and yet somehow, through it all, a little light-hearted.”

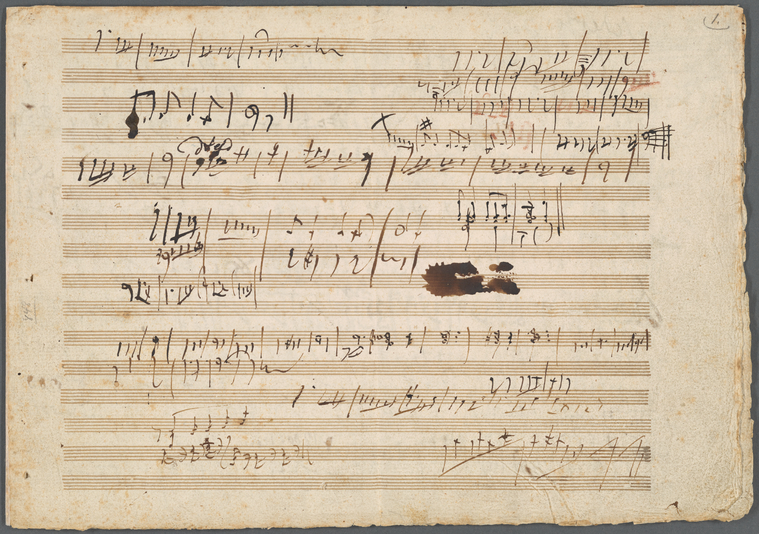

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Trio in B-flat Major, Op. 97 “Archduke”

You already knew that Beethoven had to feature somewhere in this blog about chamber music, and here is my nomination. The “Archduke” Trio, Op. 97 is widely acclaimed as one of the finest achievements in the trio form and, indeed, in classical chamber music generally. A scholar writes, “The principal themes of the work attract immediate attention for their suppleness and cantabile character… and the themes are linked together by a strong family likeness and thus engender a powerful sense of unity in the work as a whole.”

Sketches for Beethoven’s Archduke Trio

It was written with the Habsburg noble Archduke Rudolph in mind, who was also Beethoven’s only composition student. Beethoven complained that these lessons interfered with his own composing schedule, but since the Archduke was one of his most important patrons, he was careful not to tell him directly. The composer performed at the piano at the premiere, and it was one of his final concert appearances. The great violinist and composer Louis Spohr reports, “On account of his deafness there was scarcely anything left of the virtuosity of the artist which had formerly been so greatly admired. In forte passages, the poor deaf man pounded on the keys until the strings jangled, and in piano, he played so softly that whole groups of notes were omitted, so that the music was unintelligible unless one could look into the pianoforte part. I was deeply saddened at so hard a fate.”

Johannes Brahms: Piano Trio in C minor, Op. 101

In the wondrous universe of chamber music, the piano trio “is one of the most difficult forms to manipulate, and one that is seldom satisfactory in balance.” Initially, the piano was simply not equipped to compete with the string instrument, and once the piano became stronger in construction, the violin and cello struggled to keep up. Instrument makers introduced some improvements to the strings, including the raising of the bridge, the adoption of a modern bow, and the inclusion of metal strings. That’s how a new type of balance was created in chamber ensembles, and the power of the piano was now matched by a string sound that “was much fuller and more penetrating.”

Brahms at the piano

Some commentators consider the expansion of the piano’s range to be “among the most important first contributions to the trio’s growth.” In the featured Brahms Trio Op. 101, you can easily hear how the composer pushed the music towards both extremes of the keyboard. It almost seems that Brahms might have needed a larger body of strings to compete and fully balance the almost orchestral sound of the piano.

Rebecca Clarke: Piano Trio in E-flat minor

It often seems that chamber music has been firmly in the hands of male composers. Of course, that’s not entirely correct as it mainly reflects how the history of music has been written. Just have a listen to the wonderful piano trio by Rebecca Clarke, who was born and raised in England but relocated permanently to the United States after the outbreak of World War II. She was one of the first female musicians in a fully professional ensemble when Henry Wood admitted her to the Queen’s Hall orchestra. Clarke was also the first woman to study composition with Charles Stanford at the Royal College of Music. Clarke has been described as “the most distinguished British female composer of the inter-war generation.” However, lack of encouragement and even hostile discouragement made it difficult to have her compositions published. The works published during her lifetime were largely forgotten, and a good portion of her music has yet to be published. More recently, the Rebecca Clarke Society was established in 2000 to promote the study and performance of her music, and we are sure to hear many more of her finely crafted chamber works in the future.

Joseph Haydn: Piano Trio No. 39 in G Major, “Gypsy”

Can you believe that Joseph Haydn composed 45 Piano Trios? His early piano trios are still composed in the style of baroque trio sonatas, and they “have little in common with later works in this genre.”

Haydn in London

To be sure, these works served as light musical entertainments for the aristocratic elite in Vienna, and many have only two movements. His later trios were created for English publishers in order to satisfy the great demand for this kind of chamber music in London. The piano trio was greatly in demand, and the virtuoso piano parts might well have been written with the keyboard skills of particular performers in mind. The string parts are more restricted in scope, and the violin only plays the melody

at some time and is often doubled by the piano when it does. The cello part is very much subordinated, usually just doubling the bass line in the piano. The great scholar and pianist Charles Rosen discusses and defends this asymmetry, relating it to the sonority of the instruments of Haydn’s day: the piano was fairly weak and tinkling in tone, and benefited from the tonal strengthening of other instruments.

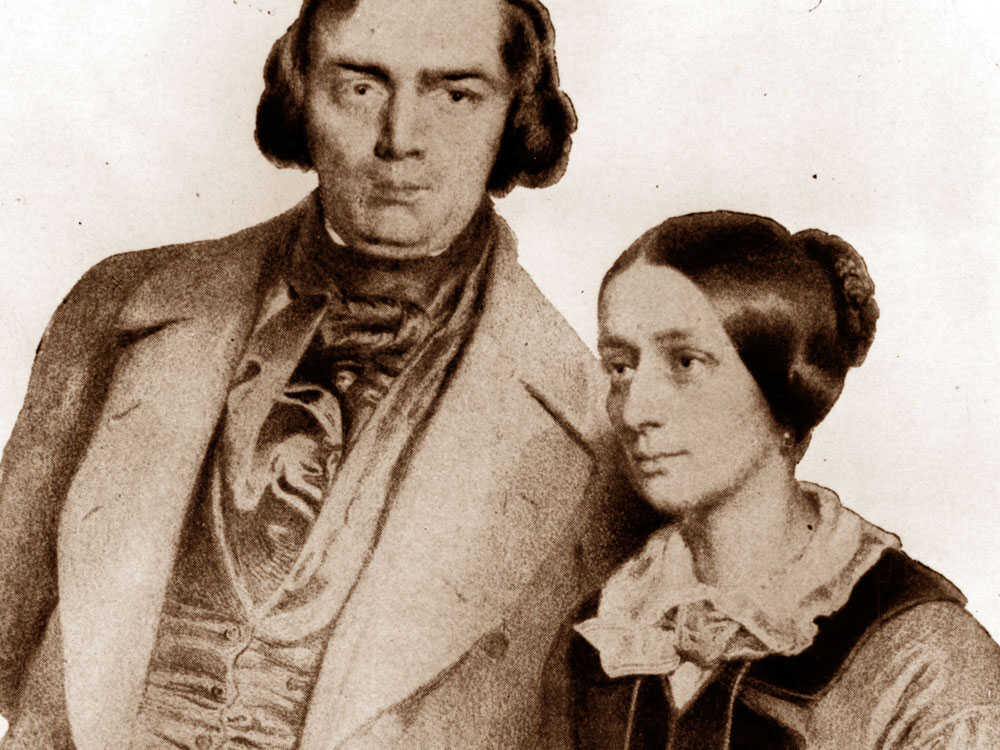

Robert Schumann: Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 63

I started this chamber music blog with Schubert, and I hope you don’t mind that I am concluding it with an astonishing piano trio by Robert Schumann. Schumann greatly admired the Mendelssohn piano trios, and he was initially shy in getting started on at genre. Some commentators hear in the Schumann D-minor trio “a wayward and nervous work, displaying an attractive element of fantasy and unpredictability, but less security of technique.”

Robert and Clara Schumann

Maybe that’s precisely why I really like this particular composition because it alternates moments of great exuberance with quiet and introspective moods. You can clearly hear the voices of Florestan and Eusebius at work. In this chamber music blog of the 10 most beautiful piano trios I have had to leave out many more astonishing works; I am sorry that I could not include them all, but maybe you could let us know in the comment section what other piano trios you would like to see featured.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Can we expand to eleven and include, by no means at the bottom, Mendelssohn’s No. 1 in D minor? And I’ll be iconoclastic and prefer the later Beaux Art recording with Daniel Hope and Antonio Meneses to the earlier classic. The late Menachem Pressler is of course imperishable in both.

I’ve played all the Beethoven, Brahms Trios and others for 40 years, and your list fails to include Rachmaninoff’s?

Faure’s D minor trio op.120. Concise but passionate.

I don’t think I’d have as much appreciation for the rest of them if it weren’t for the “Dumky,” the piece that made me fall in love with piano trios. Although Schubert is my favorite generally, for this form I prefer later composers. The Arensky is a real treat, as are Saint-Saëns’s. Of Beethoven’s, I prefer the “Ghost”

How could anybody overlook Shostakovich’s Trio in e minor op. 67.?! You should listen to the unforgettable recording of Argerich/Kremer/Maisky.

And what about Tchaikovsky’s elegiac trio op. 50? Never heard such a cunning & moving set of variations written for this combination of instruments – or any other, for that matter…