The chaconne or ciacona in Italian, is a dance with a double life. When it first appeared in Spain in the late 16th century as a transplant from the New World, it was a quick-tempo dance song, where the texts were mocking and the dance movements suggestive. This chacona by the Spanish composer Juan Arñes is one of the earliest known examples of the dance.

Juan Arañés: Chacona – A la vida bona (Hespèrion XX; Jordi Savall, cond.)

In this song, the song is about how the sound of the chacona enraptured the singer and if even a monk or nun heard it, all prayers would cease.

By the early 18th century, it had evolved into a slow triple meter piece with no musical text, just instruments. The dual nature of the chaconne continued, though, with 17th-century works with a recurring bass pattern also being called chaconnes.

One of the clearest of the Baroque chaconnes with a recurring bass pattern is Monteverdi’s madrigal duet with accompanying bass, Zefiro torna. The bass pattern you hear at the beginning is 2 measures long and recurs some 30+ times through the piece until the dramatic stop just before the end. After the singer has gotten over his sadness (…only I, abandoned and alone in the wilderness) he returns to the chaconne bass with his final happiness about singing.

Claudio Monteverdi: Madrigali e canzonette, Libro nono – Zefiro torna e di soavi accenti (Delitiæ Musicæ; Marco Longhini, cond.)

Clearly, with a recurring and solid bass line, this music could be danced to, but it was really intended to give the two tenors a solid base against their increasing vocal pyrotechnics.

To return to the ciacona as dance music, we have an example by the Spanish composer Luis de Briçeño with his Caravanda Ciacona, danceable and sometimes called an improvisation. Briçeño was in Paris in the early 17th century and wrote a Metodo mui facilissimo para aprender a tañer la guitarra a lo español, published in Paris in 1626, to bring the strumming, resqueado, style of guitar player to France. The book includes many popular dances from Spain, including the ciacona.

Luis de Briceño: Caravanda Ciacona (Private Musicke; Pierre Pitzl, cond.)

A dance teacher, known only through his books as Mr Isaac, joined with the composer James Paisible, and created a set of dances for the court of Princess, then Queen Anne. They were assembled by the dancer and teacher John Weaver and published in 1706.

The music for this Chaconne can be dated to Amsterdam in 1688 and when published in 1706, was written to describe the work as danced by Princess (later Queen) Anne when she hosted a ball for her brother-in-law William III’s birthday in November 1688.

Isaac: A Collection of Ball-Dances perform’d at Court: Mr Isaac’s The Favorite, 1706

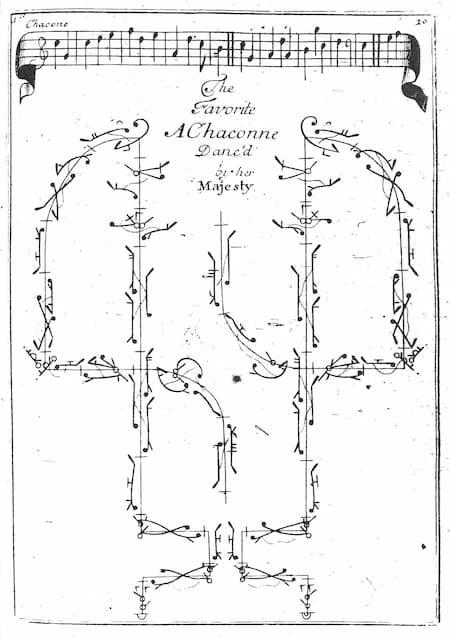

Tomlinson, in his 1735 book explaining the Art of Dancing, describes the Chaconne or Passacaille step as being comprised of 3 movements: a bound, a hop, and a bound. He then goes into detail (paraphrased): it is usually taken from the 3rd position: with the left foot disengaged and at liberty behind the right, begin by making a bound, accompanied by a sink or bending of the knees, from when the body is thrown into the air, only turning a half turn to the right hand and coming down on the toe of the left foot on the first note…and so on, going on for another page, just to get you through the first few steps.

Tomlinson: The Art of Dancing Explained…. The Passacille or Chaconne, plate 12, 1735

Briçeño was successful because we see in the following generation chaconnes appearing in operas by Lully and Marin Marais. For both composers, Lully in Roland and Marais in Ariane et Bacchus, the operas end with extensive chaconnes, intended to balance the ouverture at the beginning of the opera. These works were a series of variations over a set chord progression and perfect for a final long dance sequence.

Marin Marais: Ariane et Bacchus Suite – Act II Scene 6: Chaconne (Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra; Barthold Kuijken, cond.)

In Germany, we have the dance suites of Heinrich Biber, which he called Balletti or Arien, which include ciacona movements.

Heinrich Biber: Balletti a 6 – XII. Ciacona (Clemencic Consort; René Clemencic, cond.)

German composers were fond of the ciacona, with examples by Buxtehude, Telemann, Bach, and even Beethoven, making use of it through his 32 Variations in C minor.

J.S. Bach: Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004 – V. Ciaccona (Ilya Kaler, violin)

After this, the ciacona / chaconne / ciaccona died down for a century or so.

The use of the recurring bass pattern was a stabilizing factor for the chaconne and eventually became the reason for using a chaconne. There was a resurgence in the chaconne in the 20th century with composers from John Adams and Philip Glass through Bernd Alois Zimmermann using in their works. Its popularity has continued in the 21st century. American composer Jennifer Higdon, in her 2008 Violin Concerto bases her second movement on several chaconnes, now reduced to repeated chord progressions rather than a single repeating bass pattern.

Jennifer Higdon: Violin Concerto – II. Chaconni (Hilary Hahn, violin; Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra; Vasily Petrenko, cond.)

From wild dance to patterned dance to strong support, the chaconne has had one of the most diverse histories of all the dance types we’ve examined so far.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter