We saw in the Baroque dance suite that the dances were in pairs: Allemande–Courente and then Sarabande–Gigue. Those dances had tempos of slow/fast and this continues with our next pair, the Pavane and Galliard.

The Pavan came from Italy and our first printed sources for the music come from 1508 from the composer Joan Ambrosio Dalza. His book of lute music included five pavane alla venetiana and four pavane alla ferrarese. On the title page of the book, these works were collectively described as ‘padoane diverse’, which gives us the clue that they came from the city of Padua. Another theory has it that ‘pavane’ comes from the Italian word ‘pavona’ or ‘peacock’ indicating the parallel dignity of the dance and the spread of the peacock’s tail. In the dance, the couples walk and pause and exhibit their fine clothing.

Joan Ambrosio Dalza: Pavana alla ferrarase (Lynda Sayce, lute)

Joan Ambrosio Dalza: Pavana alla venetiana (Cappella Musicale San Giacomo Maggiore; Roberto Cascio, cond.)

The pavane was a slow dance. Arbeau’s 1588 book, Orchésography, describes it as a dance for many couples in procession. Each dancer was free to add his own ornamentation to his steps. One of the uses for the pavane would be a stately procession around the room to show off one’s attire. It is said that the halting and hesitating step that brides take to the altar (step – pause, step – pause) is a relic of the pavane.

Renaissance Dance Pavane

Now that you’d shown off your fine clothes, it was time to dance and that’s where the galliard kicks in.

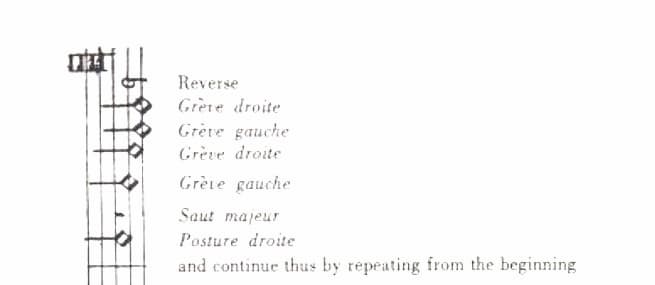

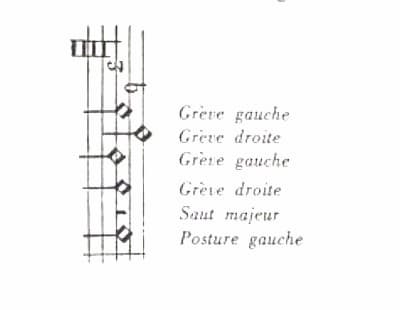

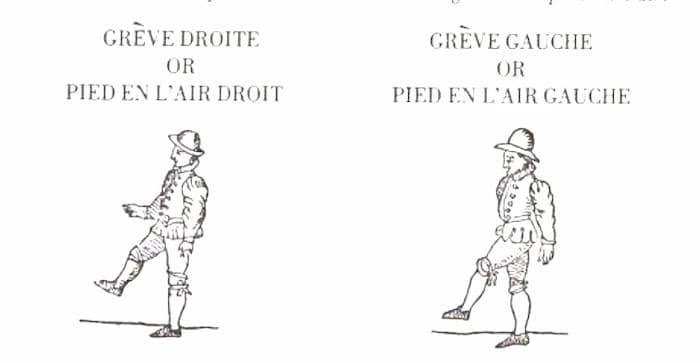

The galliard was a lively dance with jumps and pauses. The basic dance consisted of 4 ‘grèves’, where the dancer hops on the ball of one foot while making a gesture with the other foot as though to kick someone, and then ending with a big jump with two feet (saut majeur) and closing with a posture of rest, with one foot in front of the other – the jump and the rest together are called the ‘cadence’. Of course, extra motions could be added just as adding beat in the air while doing the big jump, and so on. These 5 steps: the grèves and the cadence were known as the cinque pas.

Arbeau: Orchésography: The grève done with the right and left foot, 1588

The dance is fast, but then the music must be slow enough to accommodate all these athletic kicks and jumps. Arbeau said that the galliard must be slower for big men than for small men since the big men will take longer to execute the steps.

To see a galliard in dance, with increasingly complex steps, but still with the cinque pas as the basis, this video gives an example:

Galliard Performed by Students of Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance

As you can hear, the music isn’t fast, but the dancers may have some complex actions to execute.

Arbeau, in laying out the galliard, made it a paired dance: it starts on the left foot, and then after the cadence, starts again on the right foot. After these 10 steps, you start again on the left foot.

Arbeau: Orchésography: The Galliard, 1588

Arbeau goes on to urge dancers to be in control of their movements so that damsels don’t show their knees from bouncing around and to take care not to kick their partners in their motions.

Once you conquered the basic steps, the flourishes could be added. One of the most infamous of these was the volta or as it was known in England, lavolta. During the volta, the woman is held in the air by the man as he turns 270 degrees, all of this taking place during one 6-beat measure. This would replace the cinque pas.

The Volta

This one starts with a more standard galliard before launching the lavolta step.

Lavolta

Arbeau thought this particular figure was unduly vulgar for something to be done in a gentlewoman’s ballroom. As you can see in this painting, the woman is at an angle to the man and he’s supporting her in the air with his leg. This is how it was described in Arbeau, although not how it was done in the videos.

Unknown: Dancing the La Volta, ca 1580 (Penshurst Place, Kent)

John Dowland: Captain Digorie Piper’s Galliard, P. 19 (New York Kammermusiker)

These two dances were dances of the court, being developed without folk-music antecedents. As you can see in the video, and as described by Arbeau, they begin with a bow to one’s partner. The dances were designed to show off one’s clothes and then one’s skill on the dance floor. The galliard, in particular, could be danced on a number of different levels – the simple steps of a beginning or the more complex jumps and kicks that could be added as one grew in confidence and ability.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter