One of the few instruments of the orchestra that’s named for a person, the saxophone, was named after its inventor, Belgian instrument maker Adolphe Sax (1814–1894). His father, Charles-Joseph Sax (1790–1865) was also an instrument maker and had established a workshop in 1815 in Brussels for making brass and woodwind instruments. Charles-Joseph Sax was an innovator in instrument design and had his own patents on instrument improvements.

Adolphe Sax started his musical life in his father’s workshop and attended the Brussels Conservatory, studying flute and clarinet. His first instruments were flutes, an ivory clarinet, and a 24-key clarinet, which he played and exhibited in 1835. In 1838, he took out a patent on a bass clarinet that was better than any of its competitors and it is thought that this work started him towards the development of the saxophone. He had many important friends in the musical world, including the composers Berlioz, Rossini, Halévy, and Meyerbeer, and the music historian Fétis.

Adolphe Sax, 1860–1870 (Gallica: ark:/12148/btv1b84247735)

His workshop in Paris soon started turning out instruments with his name on them: saxhorns (patented in 1845), saxotrombas (patented 1845), and saxophones (patented in 1846). Every instrument seemed to come under his eye for improvement: bassoons, military bugles, trombones, kettledrums, double basses, and pianos.

It is thought that it was his experiments with the ophicleide, a brasswind instrument with keys that are related to the bugles and trumpets. It came in a number of different sizes (one instruction book mentions six sizes), but the bass version was the most common.

bass ophicleide in B♭, c. 1830-1850 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum); Alto ophicleide in F or E♭, c. 1830–40 (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum); and the rare soprano ophicleide in B♭, c. 1850

(New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The ophicleide has its virtuoso soloists, but its most common use was as the bass in bands. Composers including Berlioz, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Verdi, and Wagner wrote music for the instrument; in the modern orchestra, it has been replaced by the tuba.

Sax scored a major triumph when, through a competition, his sax-named instruments were adopted by the French military bands, giving him a virtual monopoly. His rivals did not take this well and he was soon buried under a blizzard of lawsuits, was attacked in the media, had his best workers lured away with higher salaries, had a fire in his factory, and was physically attacked. Some of his lawsuits were so long-lasting that they were still undecided at his death.

The change from a brasswind ophicleide to the reed-wind saxophone stabilized the instrument’s sound. The instrument was a combination of some pre-existing models: the metal body from the ophicleide, a mouthpiece like that of the bass clarinet, keywork developed from clarinet and flute systems, and so on. In 1846, Sax patented his ‘saxophone’ and by 1850, it was available in 6 sizes and multiple keys: sopranino, soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, and bass.

Saxophones: sopranino to contrabass (Selmer)

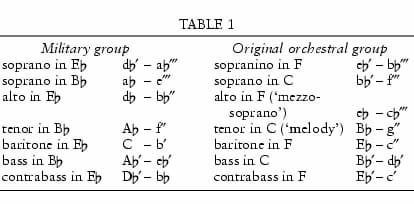

There were separate military and orchestral instruments, based on different keys.

Table of different sizes of saxophone sold by Sax (New Grove Dictionary)

The instrument quickly drew praise from French composers and critics. They liked its range of sound, described as full, soft, sonorous, and powerful, and its tonal quality. It could play with the very highest instruments of the orchestra and support weaker instruments. By the 1850s, the saxophone was being taught in conservatories and composers put it into their music. Orchestral music and operas that have sax parts include Ambroise Thomas, Hamlet (1868); Bizet, L’Arlésienne (1872); Massenet, Hérodiade (1881) and Werther (1892); Milhaud, La Création du monde (1923), and Ravel, Bolero (1928). Outside France, composers such as Strauss, Symphonia domestica (1902–3) and Gershwin, Rhapsody in Blue (1924) used the instrument to great effect.

Once the instrument was established, composers quickly wrote concertos for it. Here’s a survey of saxophone concertos by range.

Jennifer Higdon’s 2006 Concerto for Soprano Saxophone who wrote her work to show off the power and beauty of the saxophone, particularly recognizing the soprano saxophone for its ability to produce ‘a tone of warmth and a real agility that allows it to sing like none of the other instruments….’. She made an arrangement of her 2005 Oboe Concerto at the request of sax players to create this new Concerto.

Jennifer Higdon: Soprano Saxophone Concerto (Carrie Koffman, soprano saxophone; Hartt Wind Ensemble; Glen Adsit, cond.)

Paul Creston’s 1941 Saxophone Concerto, Op. 26, written for alto sax, was part of a movement in the 1930s and 1940s to convince concert-goers that the saxophone was not simply an instrument in the jazz world, but that it had a real place in classical music. Creston wanted to ‘demonstrate the capabilities of the E flat alto saxophone as a solo instrument’ and its premiere was planned to reach the largest possible audience. It was given its premiere on a 1944 broadcast by the New York Philharmonic (then the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York) under conductor Artur Rodzinski, with Vincent J. Abato as soloist. In the third movement, Creston showcased the instrument’s technical and dramatic capabilities.

Paul Creston: Saxophone Concerto, Op. 26 – III. Rhythmic (Timothy McAllister, alto saxophone; National Orchestral Institute Philharmonic; JoAnn Falletta, cond.)

Kalevi Aho’s 2015 Concerto for Tenor Saxophone and Small Orchestra was inspired by an experimental jazz concert at the Helsinki Conservatory of Music. The performer at that concert said that there was little music for tenor sax and orchestra and Aho stepped up to the challenge. The work, in a single movement but broken up into contrasting sections, gradually exposes the expressive possibilities of the instrument. At the very end of the work, in the Epilogo, we hear many different qualities of the instrument.

Kalevi Aho: Tenor Saxophone Concerto – Epilogo: Andante (Esa Pietilä, tenor saxophone; Saimaa Sinfonietta; Erkki Lasonpalo, cond.)

Werner Wolf Glaser’s Baritone Saxophone Concerto is a 1992 work that contrasts the ‘volume and sound and sonority’ of the baritone sax with the transparency of a string orchestra.

Werner Wolf Glaser: Baritone Saxophone Concerto – I. Lentando (Linda Bangs, baritone saxophone; Ensemble del Arte; Hans Stadlmair, cond.)

When saxophones are played as ensembles, the broad range of instrument sizes works to its advantage to cover the necessary musical range.

An early work for saxophone quartet was Jean-Baptiste Singelée’s Opus 53 Quartets, written in 1857.

Jean-Baptiste Singelée: Saxophone Quartet No. 1, Op. 53 – IV. Allegretto (Christian Debecq, soprano saxophone; Guy Goethals, alto saxophone; Ronald Schneider, tenor saxophone; Ulrich Berg, baritone saxophone)

French composer Jacques Ibert wrote most of his saxophone works between the mid-1930s and the early 1960s. His light style was well suited to the saxophone’s sound and in his Petit quatuor from 1935, we can hear his playfulness.

Jean Françaix: Petit quatuor – I. Gaguenardise (Kenari Quartet)

With such a wide range of sounds available in the saxophone family, it’s not surprising that saxophonists have raided works for other instruments. One example of this is the arrangement of Vivaldi’s Winter from the Four Seasons for saxophone ensemble. With just a quartet of saxophones (soprano, alto, tenor, and baritone) The Whoop Group from Poland covers the sound and ideas of Vivaldi’s violin concerto.

Antonio Vivaldi: The Four Seasons – Violin Concerto in F Minor, Op. 8, No. 4, RV 297, “L’inverno” (Winter) – I. Allegro non molto (arr. for saxophone ensemble) (The WHOOP Group)

As one of the last instruments to be added to the orchestra family, the saxophone was able to supplement the sound of other instruments in the orchestra. Its inventor, Adolphe Sax, was another kind of radical upstart in the field of musical instrument builders. Between the inventor and his invention, a new sound came to the orchestra enabling composers to modernize their ideas.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter