The violin, the best known of the instruments of classical music, is known by its shape – an hour-glass waist and an arched bridge. These are our first clues that this is a bowed instrument – the waist on the instrument permits a bow to sound the strings and the bridge keeps the strings separated so that they can be played individually.

Modern violin

The first violins are shown in paintings from the 15th century; instruments before that lack the waist, as in this picture of one of the violin’s predecessors, the vielle, although they do have rudimentary bridges.

Medieval violin – The Vielle

By 1550, the violin, at least in Italy, had its classic shape; elsewhere, they were still experimenting with acoustics and shapes. The early violins were not held under the chin as they are today but were held against the chest.

Gerrit Dou: The Violin Player, 1665 (Dresden: Staatliche Kunstsammlung)

The sounding part of the violin, the strings, started out as being made from animal gut (sheep, not cat). Soon, however, it was found that winding silver around the gut strings gave a better response. These are still used today by professional players, but most amateur players are using either silver wound around steel or silver over nylon or similar synthetic material.

The bow is a complicated part of the violin. It holds the bow hairs in tension so that they can make the strings sound, but also has to be able to release that tension when not being played. The ‘frog’ controls this tension and provides a place for the violinist to hold the bow. At the other end of the bow, the hair is held by the violin tip.

Violin frog. The metal screw at the end of the bow is used to tighten the frog (K. Gerhard Penzel)

Violin Tip holding the horsehair (K. Gerhard Penzel)

The bow hair is made of horsehair, usually about 160 to 180 individual hair, attached together to form a ribbon.

Violin bow

To aid the violin bow in making the strings vibrate, the bow is rubbed with resin, which comes from trees. The resin allows the bow hairs to ‘grip’ the strings and increase the vibration.

Violins and other string instruments were regarded as more ‘noble’ than wind instruments. For her private study, Isabella d’Este commissioned a cycle of allegorical paintings by artists Mantegna, Perugino, and Lorenzo Costa. The paintings show musical instruments, with string instruments ‘consistently associated with virtue, spiritual love, and harmony, while wind instruments are associated with vice, sensual love and strife’.

The music for the violin is considered to be some of the most beautiful ever written. The instrument’s singing quality has been a prime part of the love for its sound.

The Baroque period produced the music we love including Vivaldi’s violin sonatas that we know as The Four Seasons. The ability of the violin soloist to bring us the birds and other sounds of spring is an intrinsic art of the instrument.

Antonio Vivaldi: The Four Seasons: Violin Concerto in E Major, Op. 8, No. 1, RV 269, “La primavera” (Spring) – I. Allegro (Alice Harnoncourt, violin; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cello; Herbert Tachezi, harpsichord; Concentus Musicus Wien; Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond.)

J.S. Bach’s violin concertos combine finely spun melodies with repeated bass figures.

J.S. Bach: Violin Concerto in A Minor, BWV 1041 – I. Allegro (Takako Nishizaki, violin; Capella Istropolitana; Oliver von Dohnányi, cond.)

Giuseppe Tartini attributed the idea of his Devil’s Trill sonata to a dream he had where the Devil offered him a violin on which he played music so striking that he, upon awakening, tried to recapture it. His sonata starts with a Larghetto and then becomes energized in the Allegro. Tartini’s writing requires extreme violin techniques for the time, including multiple stopping (playing multiple notes at once) and trills that accompany a melody on another string.

Giuseppe Tartini: Violin Sonata in G Minor, “The Devil’s Trill” (Bin Huang, violin; Hyun-Sun Kim, piano)

Moving into the Classical era, composers began to use the violin’s showstopping qualities more and more. In Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata, the violin sings and dances.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major, Op. 47, “Kreutzer” – III. Presto (Takako Nishizaki, violin; Jenő Jandó, piano)

Mozart wrote violin sonatas over a span of some 25 years. His first ones were written while he was still a child and touring Europe as a child prodigy. His last sonatas were completed after his death by his students. The last one he completed himself, Violin Sonata in A major, K. 526, is dated 24 August 1787. Both the violin and the piano share musical content and it may have been influenced by the death in London of the composer Carl Friedrich Abel, whom he had known as a child in London. The final rondo uses a theme by Abel.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Violin Sonata No. 35 in A Major, K. 526 – III. Presto (Christian Tetzlaff, violin; Lars Vogt, piano)

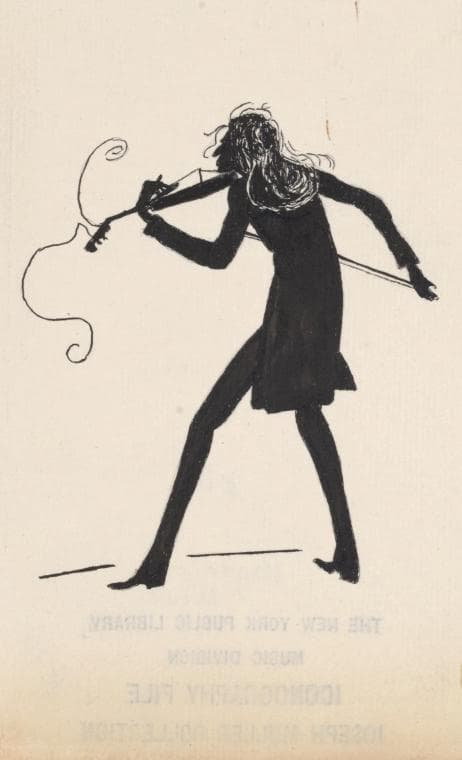

Italian violinist Niccolò Paganini used his reputation as a devilish player to create a true celebrity buzz around his performances. His technical and musical skills astounded his listeners, and he wasn’t beyond a bit of showmanship, such as continuing to play a piece although his strings were breaking.

Paganini the violinist silhouette (New York Public Library: Muller Collection)

Niccolò Paganini: 24 Caprices, Op. 1 – No. 24 in A Minor: Tema quasi presto (Leonidas Kavakos, violin)

With performers such as Paganini, the idea of the violin soloist (whether influenced by the devil or not) took wing. Performers such as Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifetz in the 20th century were violinists who brought even higher levels of technical expertise.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30, No. 3, “Champagnersonate” – I. Allegro assai (Fritz Kreisler, violin; Sergey Rachmaninov, piano)

Henryk Wieniawski: Scherzo-tarantelle, Op. 16 (Jascha Heifetz, violin; Emanuel Bay, piano)

In the modern day, David Oistrakh and Yehudi Menuhin captured our attention, but it’s been the women players who have come to the fore. Nicola Benedetti, Midori, and especially Hilary Hahn have made the violin more exciting than ever.

Paul Moravec: Blue Fiddle (Hilary Hahn, violin; Cory Smythe, piano)

This isn’t a list of the best violin pieces but merely a selection of some of the interesting pieces in the violin world. Composers worked with violinists, or were violinists themselves, to create works that brought out the best in the instrument. When his violin concerto, op. 77, failed in the concert halls, Brahms went on tour with the violinist Joseph Joachim to workshop the piece (as we would say today). Traveling with a full grand piano and Joachim’s seven Stradivarius violins, they toured through Romania, giving concerts and working on repertoire. Brahms came back regenerated both as a performer and a composer and the Violin Concerto went onto its own fame.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter