In previous blogs we listened to a number of beautiful piano quintets scored for piano and a string quartet. Robert Schumann came up with this arrangement in 1842, and it became the standardised scoring for much of the 19th century and beyond. For composers writing before and after 1842, however, the piano quintet could also mean something slightly different.

Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet performance

In its simplest definition, the piano quintet is a work of chamber music written for piano and four other instruments. Composers relied on matters of taste and practicality in their choice of instrumentation, and in this blog we will explore piano quintets that combine the piano with four less conventional instruments.

The best place to start are piano quintets by Mozart and Beethoven, both scored for piano, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon. These works are clearly piano quintets, but they are usually described as “quintets for piano and winds,” so as to distinguish them from compositions for piano and four strings.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Quintet in E-flat Major, K. 452

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) wrote to his father in March 1784, “On the last three Wednesdays of Lent, I have planned three subscription concert… I shall later give private concerts in aristocratic salons or in one of the city’s theatres.” One of these aristocratic salons belonged to Prince Aloys Liechtenstein, who was putting together his own wind band. Undoubtedly, Mozart thought that a work prominently featuring wind instruments would impress the young Prince, and thus K. 452 was born.

Portrait of Mozart by Johann Nepomuk della Croce

The Quintet in E flat major for piano, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon, K452, first sounded 21 March with Mozart performing at the piano. Sadly, the Prince had scheduled his own musical event at his palace and did not attend the premiere. In the event, Mozart wrote to his father a couple days later, “I consider it the best work I have ever written.” The unusual combination of instruments presented a difficult task for Mozart, “as single winds, as opposed to pairs, pose problems of blend,” so Mozart explored the numerous different permutation of the instruments to produce different sonorities, and constructed music of short phrases and motifs for variety.

That Mozart had to work hard on this piece is confirmed by extensive sketches for the opening movement. In this case, the impression of ease and spontaneity had to be worked out on paper. The work is scored in the three movements of a concerto. A slow introduction leads into the first movement proper, and here Mozart demonstrates the range of tonal resources available from his five instruments. A lyrical dialog between the piano and winds sounds in the slow movement, and a high-spirited rondo concluded with an opera buffa coda. By the way, Prince Liechtenstein finally managed to get his wind band together in 1792.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Quintet for Piano and Winds in E-flat major, Op. 16

Mozart’s marvellous achievement was recognized by Ludwig van Beethoven, who greatly admired the work. But what is more, he composed his own piano quintet modelled on Mozart. The Beethoven Op. 16 is written in the same key of E-flat major, scored for the same instruments, and sporting the same three-movement structure. As Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny wrote, “Beethoven’s ingenuity comes face to face with Mozart’s classical style in this delectable Quintet, which possesses in its melodies and effect, a charm which will never grow old.”

Joseph Willibrord Mähler: Beethoven, 1804–1905 (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien)

However, there is one fundamental difference between the Mozart and Beethoven quintets. Beethoven approached the composition from the standpoint of a piano virtuoso. As such, the piano parts of his early chamber music were written to highlight the strengths of his playing. Virtuosity aside, he also composed music with glowing passion, exuberance, heroism, nobility, and dramatic pathos.

Just like Mozart, Beethoven opens with a slow introductory dialog following a fanfare unison in the tonic key. While the winds initially take the lead, the piano quickly steps into the limelight with a solo flourish. There is much emphasis on the singing quality of the piano in the “Andante cantabile,” with the delicate theme introduced by the piano. And the concluding “Rondo” is like a game of musical chairs, with a big solo cadenza in the first half of the movement. Beethoven played the piano part himself when the work was first heard, and it is reported “he indulged in some extra improvisational activity, fooling the wind players, who at first amused and then disgruntled, were waiting to come back in.”

Johann Ladislaus Dussek: Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 41

The tradition of the touring piano virtuoso did not start with Sigismond Thalberg or even Franz Liszt. This distinct honour should rightfully be bestowed upon the Czech pianist and composer Jan Ladislav Dussek (1760-1812). From the time of his early childhood, he dazzled audiences with his virtuoso piano playing. I don’t know if it is true, but a critic wrote that “Dussek was the first pianist to sit at the piano with his profile to the audience,” earning him the appellation “le beau visage.”

Johann Ladislaus Dussek

Dussek appears to have been responsible for one more innovation, and that is the combination of the piano with a violin, a viola, a cello, and a double bass. This somewhat unusual combination of instruments for a piano quintet was probably the result of the sounding qualities of the early fortepiano. In Dussek’s time, the pianoforte still used gut strings, making the bass register sound like a harpsichord. The lighter bass register needed support and it perfectly blended with the double bass.

There is one more possible reason for the addition of the double bass. The first performance took place in London in April 1799 with the participation of Domenico Dragonetti, the first internationally significant double bass virtuoso. The passionate piano quintet foreshadows elements of musical Romanticism, particularly in the dramatic rolling arpeggios of the opening movement. The melancholic rondo melody of the third movement echoes this opening, and Dussek treats the participating instruments as equal chamber partners.

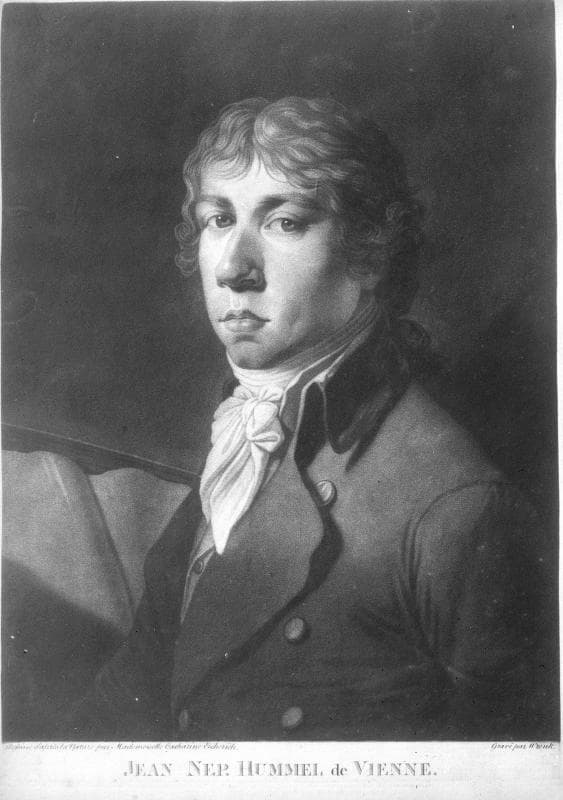

Johann Nepomuk Hummel: Piano Quintet in E-flat minor, Op. 87

Dussek’s unusual combination of instruments for a piano quintet either caught the attention of other composers or it might have been in common currency at this time. At any rate, Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) composed his piano quintet for piano, violin, viola, cello, and double bass in 1803, three years after Dussek’s effort.

The Hummel Quintet in E-flat Major, Op. 87 has been described as one of “Hummel’s finest chamber works.” Hummel was an exceptional pianist in his own right, and the quintet almost sounds like a piano concerto. Once you hear it performed on period instruments, however, it achieves a completely different balance. An annotator writes, “Hummel’s use of the double-bass is skilful and adds, especially in the last movement, a very characterful dimension.”

Johann Nepomuk Hummel

The chamber music critic Rudolf Felber writes, “The Quintet op. 87 is a masterpiece; the first movement (Allegro e risoluto assai) immediately captivates and impresses the listener with its power and passion. The peculiar main theme has a somewhat belligerent character … It is followed by the “Allegro con fuoco,” a mix of animation and exuberance with a melancholy burden … The “Allegro agitato” finale is full of carefree mirth and ends with a brilliant and effective conclusion.”

Franz Schubert: Piano Quintet in A Major, D. 667 “The Trout”

The Hummel quintet Op. 87 was certainly known to Sylvester Paumgartner, an amateur cellist and local music patron who sponsored musical evenings devoted to song and chamber music. The reason we still remember Paumgartner’s name is because Franz Schubert (1797-1828) and the baritone Johann Michael Vogl visited him during a walking tour of Upper Austria in 1819.

Schubert had free use of the music room, and he staged a number of midday concerts in the salon. Paumgartner requested Schubert to compose a work with the same instrumentation as Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s E-flat Piano Quintet, featuring the double bass. The second requirement demanded that one of the movements should feature Paumgartner’s favourite “Trout” song. That setting dates from 1817, and it quickly became one of his biggest hits.

Schubert’s Trout Quintet

The result is one of Schubert’s most famous and best-loved compositions, nicknamed after a fish. The “Trout Quintet” was Schubert’s first truly significant chamber work, and the composer effortlessly weaves some of his most delightful and magical melodies into an impressive blend of formal clarity and musical narration. In no other large work did Schubert produce so many carefree and spirited tunes. All five movements unfold in a very relaxed and graceful manner, and 4 of the 5 movements are unified by a rising piano figure, the famous water motif. That figure is taken directly from the song accompaniment and represents a delightful musical imitation of water. And most famous, perhaps, are the 6 delightful variations on the “Trout” theme in the fourth movement.

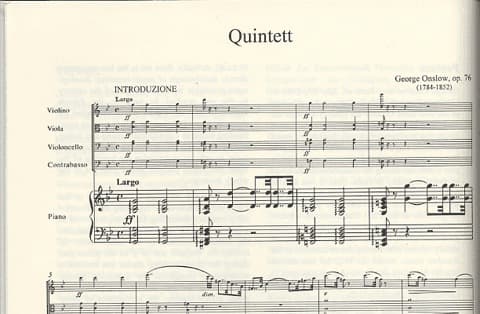

George Onslow: Piano Quintet No. 2 in G Major, Op. 76

George Onslow: Piano Quintet No. 2 in G Major, Op. 76 (Nepomuk Fortepiano Quintet)

Remember the famed double-bass virtuoso Domenico Dragonetti, who played in the premiere performance of the Dussek’s Quintet, Op. 41? Dragonetti was also known to George Onslow, a French composer of English descent and a prolific composer of chamber music. Actually, he composed 36 string quartets and 34 string quintets alongside 10 piano trios. His early quintet efforts were scored for two violins, one viola, and two cellos. At one performance, one of the cellists didn’t show up, so Dragonetti, who was there by chance, suggested that he replace the absent cellist.

George Onslow’s Piano Quintet

Initially, Onslow resisted because he thought that the combination would be unpleasant, but the resulting sound colours were rather convincing. As such, Onslow decided to start composing quintets featuring the double bass and the piano. When I say composing, I actually mean arranging, in Onslow’s case. The piano quintet Op. 76, written in 1848, is actually an arrangement of his 4th Symphony.

Onslow composed the symphony in just seven weeks in 1846. For this work, Onslow borrowed material from his “Romance” from his Piano Duo Op. 7, and the exciting finale titled “Le coup de vent” (The Gust of Wind) employs material from the opera Guise. Seemingly, this movement is suggestive of the Aeolian harp, a popular instrument at the time.

Louise Farrenc: Piano Quintet No. 1 in A minor, Op. 30

The addition of the double bass in the piano quintet also fascinated Louise Farrenc (1804-1875), one of the first successful female composers in 19th-century France. She was highly respected by her contemporaries, and Robert Schumann writes, “her works are so sure in outline, so logical in development that one must fall under their charm, especially since a subtle aroma of romanticism hovers over them.”

The first of two piano quintets by Farrenc was premiered in the spring of 1840 at a chamber music matinee hosted by Aristide Farrenc. Her musical inheritance did not originate with her French compatriots, instead she primarily turned to Ludwig van Beethoven. Or, in this case, it might have well been Franz Schubert. The “Trout” quintet premiered in Paris in 1838, and it was greeted with great admiration.

Louise Farrenc

Scored in the standard 4-movement form, the opening “Allegro” starts with strings playing in unison before sparkling triplets in the piano demand attention. Here, as in the other movements, the piano makes a prominent appearance. A highly lyrical “Adagio” leads into a “Scherzo” of hyperactivity, with the piano and violin taking turns racing towards the finish. The “Finale” alternates a serious opening theme with a bouncy secondary theme and exemplifies Farrenc’s skill in ensemble writing.

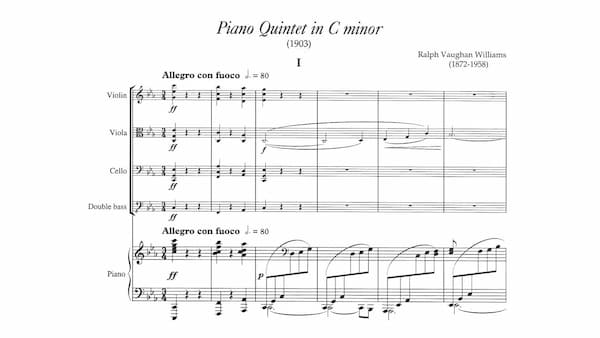

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Piano Quintet in C minor

During his formative years, Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) composed a String Quartet and a Piano Quintet in C minor. He started work on the quintet in 1903 and revised the composition in 1904 and 1905. It is scored for the same instrumental forces needed in Schubert’s “Trout,” piano, violin, viola, cello, and double bass.

The first performance took place in Aeolian Hall, London, on 14 November 1905. Seemingly, there was also a public performance in 1910 and one in June 1918. On his return from the war, Vaughan Williams withdrew several early works, including this one. According to Michael Kennedy, “his widow eventually lifted the ban on performance and publication, and the piano quintet was revived in November 1999 at the Royal College of Music.

Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Piano Quintet

There is much of Brahms in the main theme of the opening movement, particularly in some of the big gestures that almost seem to invite orchestral treatment. The lyrical “Andante” bears a resemblance to the song “Silent Noon,” composed in the same year, and the “Finale” is a theme with five variations. Vaughan Williams would use the thematic basis of this movement many years later in his Violin Sonata.

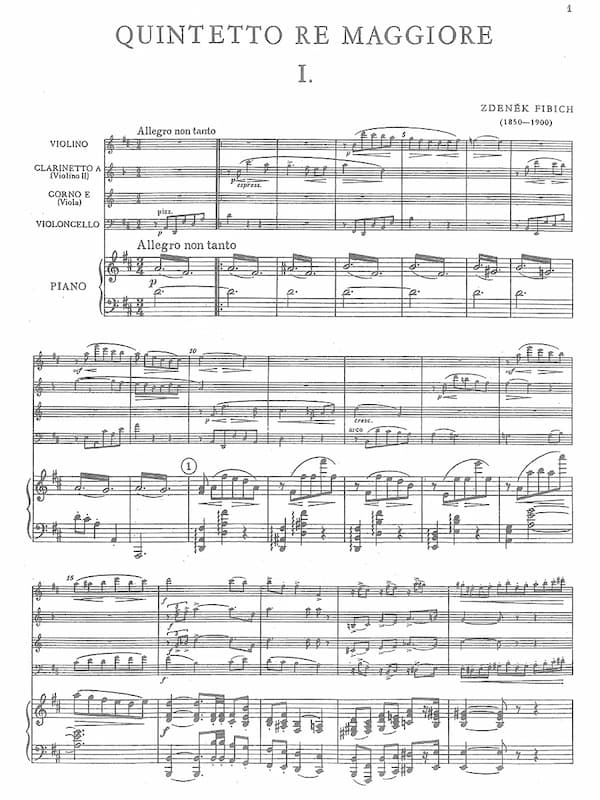

Fibich Zdeněk: Piano Quintet in D major, Op. 42 (Radoslav Kvapil. piano; The Suk Quartet)

Fibich Zdeněk: Piano Quintet in D major, Op. 42

Alongside Smetana and Dvořák, Fibich Zdeněk (1850-1900) was one of the so-called “Big Three” of 19th-century Czech composers. With his piano quintet in D Major, Op. 42, he certainly created one of the most original-sounding chamber works in the repertoire. Scored for piano, violin, clarinet, horn, and cello in 1893, the work greatly shocked his publisher because he knew he would not sell many copies. Fibich did make an arrangement for the standard piano quintet, but the original is much more fun.

Fibich Zdeněk’s Piano Quintet

We have no idea why Zdeněk insisted on such an unusual instrumentation, but much of his later works were inspired by his passionate love affair with Anežka Schulzová. We do know that she wrote the librettos for his last three operas. The opening “Allegro” unfolds as a peaceful reflection of nature, interrupted only by a brief orchestral outburst. The serene and dignified “Largo” exudes great passion, followed by a “Scherzo” reminiscent of Schubert. The “Finale,” marked “to be played with wild humour”, is a bright and joyous affair.

Nikolai Rimsky Korsakov: Piano Quintet in B-flat Major

In 1876, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) participated in a chamber music competition organised by the Russian Music Society. Korsakov submitted a String Sextet in A Major and a Quintet for flute, clarinet, horn bassoon, and piano in B-flat Major. Sadly for Korsakov, the prize was won by the Czech composer Eduard Nápravník.

In his autobiography, Korsakov recalled, “The jury found my sextet worthy of receiving an honourable mention but did not take my quintet into account. Nápravník’s Trio had been admirably performed by pianist Theodor Leschetitzky, who impressed the jury, whereas my quintet was massacred by a drudge named Cross…”

Scored in three movements, the “Allegro” is in the style of Beethoven, according to the composer. The “Andante” provides an atmosphere of Russian melancholy, while the concluding “Allegretto vivace” sounds like a dance tune that gets progressively more serious. I hope you enjoyed his little excursion into the realm of piano quintets that combine the piano with four less conventional instruments.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter