Sergei Rachmaninoff was born in 1873 in Russia. He became one of the greatest pianists of his generation, as well as one of the most famous composers.

Portrait of Sergei Rachmaninoff by Konstantin Somov, 1925 © Wikipedia

Here are a few facts about Rachmaninoff’s life and music:

- Rachmaninoff’s music is characterized by its lush and melancholy melodies. They often have a sweeping, Romantic quality to them that evokes intense emotions in listeners.

- Rachmaninoff was one of the great piano virtuosos of his day, and his works for the piano reflect his deep understanding of the instrument. His hands were massive and he was unafraid to write extreme technical challenges into his keyboard music.

- Rachmaninoff’s music is deeply rooted in the Russian tradition. This means that his compositions often contain elements reminiscent of Russian folk melodies and a real sense of national identity.

Intrigued? We hope so! Here are ten pieces of music to enjoy by Rachmaninoff:

Trio élégiaque in G minor (1892)

This trio was written when Rachmaninoff was only eighteen, but it includes many of the hallmarks of his later work: a distinctly Russian flavor, passionate chords, and a desperate melancholy.

The trio is unusual in that it only has one movement instead of the traditional three or four. Over the course of that single movement, Rachmaninoff creates variety by constantly introducing new instructions to the players: for instance, to play with animation, then passion, then resoluteness.

Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor (1900-01)

This was the concerto that made Rachmaninoff’s name, and it is still among his most popular works today. However, it had a long gestation.

The premiere of Rachmaninoff’s first symphony in 1897 had been quite a traumatic debacle, and it led to a mental breakdown.

After several terrifying years of writer’s block, in early 1900, Rachmaninoff finally began going to a neurologist. This neurologist helped him process the failure of his symphony and feel comfortable composing again. Rachmaninoff dedicated the concerto to him in gratitude.

The concerto is lush, deeply emotional, and beautifully paced and proportioned. Rachmaninoff would tour the world playing and promoting it, ensuring its spot in the classical music canon.

Cello Sonata in G minor (1901)

Rachmaninoff’s melancholy compositional voice is perfectly suited for the deep, rich tones of the cello, as evidenced by this sonata masterpiece.

A dreamy introduction gives way to typical Rachmaninoff turbulence. It soon becomes clear that this is a big work in every way, featuring big gestures and thick textures. But it is also deeply personal and, paradoxically, intimate.

Symphony No. 2 (1908)

It was a major deal for Rachmaninoff to write another symphony after the abject failure of his first. However, his work with his neurologist continued to pay off, and he pushed past his doubts to write his second symphony.

When Rachmaninoff wrote this work, he was living in Dresden for the summer with his family, trying to escape the political upheaval that would culminate in the Russian Revolution.

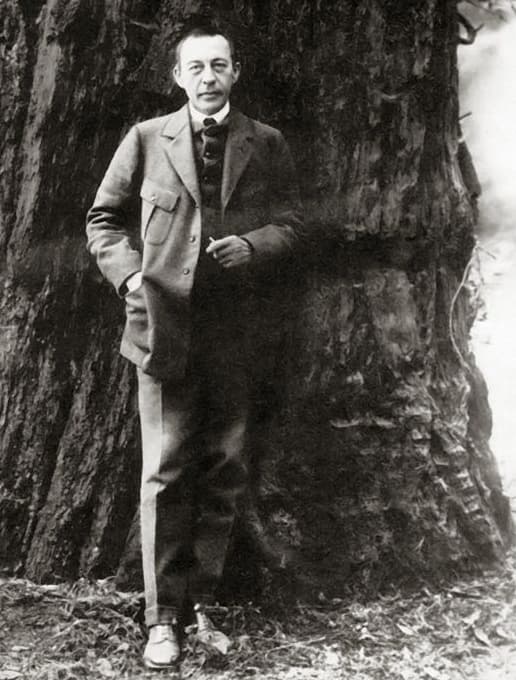

Rachmaninoff in California, 1919

Maybe that background helps to explain the ominous, hypnotic restlessness in this work. The heart of this symphony is in its third movement, a soulful adagio cushioned by sympathetic strings and featuring many yearning woodwind solos.

The premiere of his second symphony was a success, and Rachmaninoff’s confidence in his ability to write for orchestra was restored.

Isle of the Dead (1908)

Composers can be inspired by anything, but their imaginations often run especially wild when they come in contact with a piece of literature or art.

That happened when Rachmaninoff saw a black and white reproduction of the painting Isle of the Dead by Symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin.

You can practically hear the oars hitting the water as a rowboat approaches the mythical Isle of the Dead. Rachmaninoff left no detailed program, so as to what exactly happens to that nameless oarsman as they draw near to the isle, that’s up to you. Listen and see what comes to mind!

Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor (1909)

Around the same time Rachmaninoff was writing the Isle of the Dead, he also wrote his third piano concerto.

He made his new concerto diabolically difficult. (The pianist it was dedicated to actually declined to perform it.)

Astonishingly, due to his busy schedule, Rachmaninoff did most of his rehearsals of the solo part on a silent keyboard while traveling to New York to give the work’s premiere.

The public’s response to the concerto was lukewarm initially, but it was Rachmaninoff’s favorite. His continued advocacy for the work eventually ensured its position in the canon. Today it is one of the most popular piano concertos of all time.

It’s also among the most feared, with many pianists believing it’s the most difficult one in the entire repertoire.

All-Night Vigil (1915)

This is a stunning and unique work, composed for the Russian Orthodox Church’s All-night vigil service. It is written for voices alone, with no instruments.

Rachmaninoff wrote it in a burst of inspiration over the course of just two weeks, and it became one of his favorite pieces. It’s easy to see why: it’s simultaneously comforting and awe-inspiring.

Just two years later, the Russian Revolution led to the denouncement of religious traditions and religious music, quickly stripping the music of a contemporary religious context. Almost from the beginning of its existence, the Vigil would have sounded like music from another era.

Rachmaninoff requested that a movement from the Vigil be played at his funeral.

Vocalise (1915)

A vocalise is a piece of music that contains no lyrics. Instead, a singer just sings a vowel sound.

Rachmaninoff’s Vocalise is not just one of the most famous vocalises, but one of his most famous works, period.

Since there are no lyrics, the work is uniquely well-suited for adaptations and rearrangements. Here’s one for cello.

Rachmaninoff Vocalise, for Cello and Piano

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini (1934)

In 1917, Rachmaninoff fled Russia and became an exile due to the Russian Revolution. The trauma of the move, and leaving the culture of his homeland, put a damper on his creativity. After he left, he only wrote a handful of pieces.

However, a couple of those pieces were bona fide masterpieces, like this demonically playful quasi-concerto for piano, called Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.

It took a theme originally written by the supposedly devil-possessed nineteenth-century violinist Niccolo Paganini, and turned it into a Romantic Era piano showpiece.

Symphonic Dances (1940)

In 1940, Rachmaninoff summed up his career with this striking three-movement orchestral suite.

It’s a love letter to the musical culture of Russia, calling to mind the spikier works of enfant terrible composers like Prokofiev or Stravinsky, but its lush orchestration is unmistakably all Rachmaninoff.

He includes references to his life and career throughout his Symphony Dances, including a quote of his first symphony and another from his beloved All-Night Vigil.

Conclusion

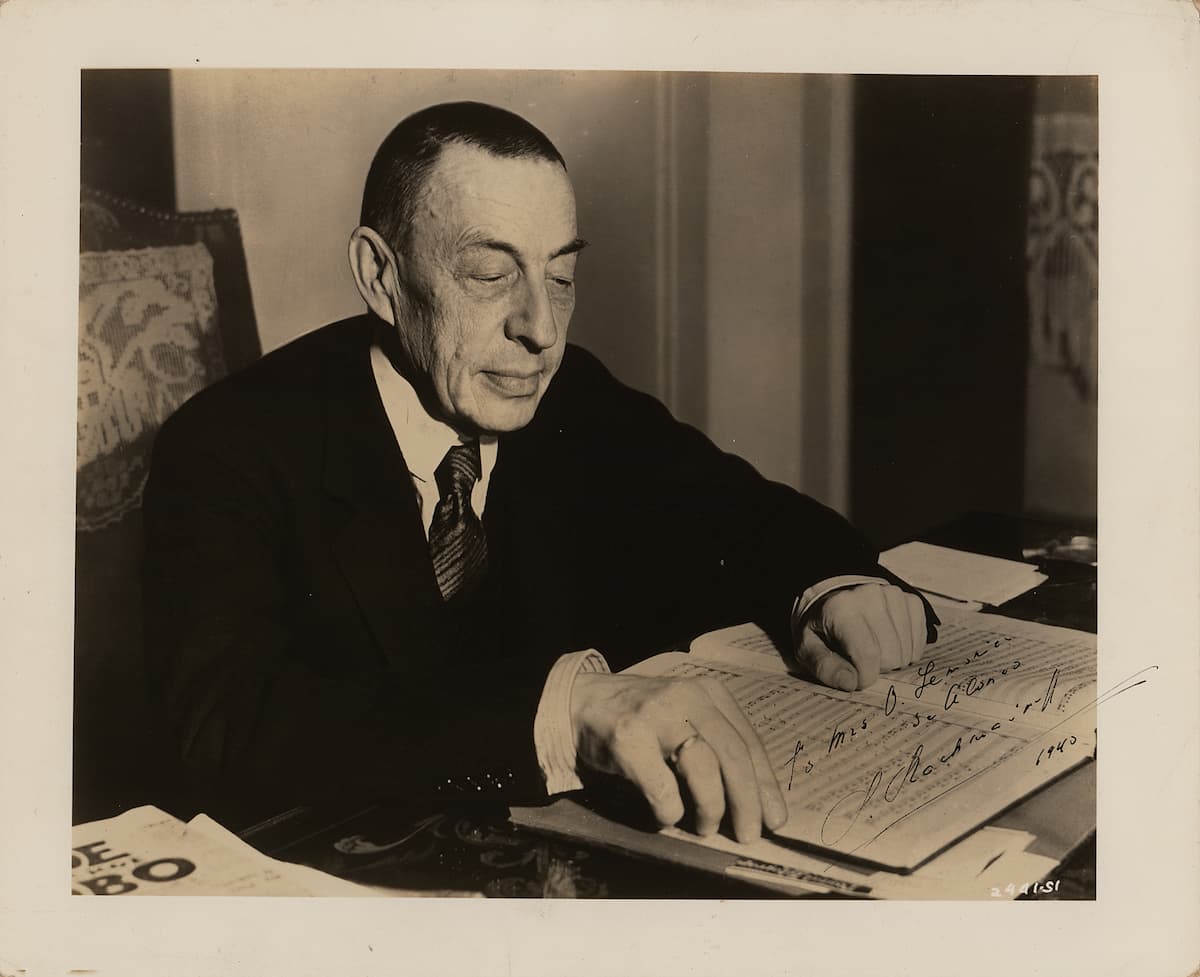

Sergei Rachmaninoff

In the 1940s, Rachmaninoff moved to Beverly Hills, California, where he lived in pleasant exile. At the same time, his health began deteriorating.

He pushed through a handful of concerts and returned to California, where he died. He wished to be buried in Russia, but the world war made it impossible. Today, his remains rest in a cemetery plot outside of New York City.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter