George Bernard Shaw, 1879

Long before George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) became a Nobel-prize winning dramatist and author of more than sixty plays, including Man and Superman of 1902 and Pygmalion of 1912, he worked as a music critic. He wrote his first musical criticisms for The Hornet after moving to London in 1876. Taking some time off to pen his five novels, Shaw joined the editorial staff of The Star in January 1888. He took over the job as salaried music critic in February 1889, and entertained readers under the penname “Corno di Bassetto.” In May 1890 he transferred to The World and continued to write weekly criticism until August 1894. Shaw did come from a musical background, as his mother was an amateur singer in Dublin. He was never formally instructed in music, but taught himself to play the piano and read scores. He even convinced his musician friend to teach him the basics of music theory and counterpoint. It has been reported that when Shaw began his literary career, “he played so much Wagner that he caused his mother, who performed primarily Italian music, to cry regularly.”

Richard Wagner: Rheingold, “Entry of the Gods into Valhalla”

Shaw: Music in London, 1890‑94

Shaw had a pretty good idea what it meant to be a music critic. He writes, “there are three main qualifications for a music critic, besides the general qualification of good sense and knowledge of the world. He must have a cultivated taste for music; he must be a skilled writer; and he must be a practiced critic. Any of these three may be found without the others; but the complete combination is indispensable to good work… Some gentlemen may write without charm because they have not served their apprenticeship to literature; but they can at all events express themselves at their comparative leisure as well as most journalists do in their feverish haste; and they can depend on the interest which can be commanded by any intelligent man who has ordinary powers of expression, and who is dealing with a subject he understands. Why, then, are they so utterly impossible as music critics? Because they cannot criticize.” Shaw’s vision of the ideal critic saw the reporter “as a vital and initiating force within the music community.” He believed that the music critic was primarily an educator, “and he recognized that even the musically uninitiated could be charmed into learning, if music criticism were made both intelligible and entertaining.”

Edward Elgar: Symphony No. 3 (completed Anthony Payne)

George Bernard Shaw, 1911

Shaw’s critiques were not merely based on his musical knowledge, but also on the extent to which he had enjoyed a performance. In essence, he brought a very personal approach to music criticism. His writings, as has been observed, “stand alone in their mastery of English and compulsive readability.” Written with customary wit and cutting humor, they make for entertaining reading. For Shaw, his articles had to be entertaining and understandable for the layman, as he wrote, “I purposely vulgarized musical criticism, which was refined and academic to the point of being unreadable and often nonsensical.” Shaw was seriously disliked by most critics and musicians, but adored by his general readers. He readily made enemies, because “poor performance was a personal insult to be treated accordingly.” Growing up, the notable Dublin impresario, singing teacher and conductor George John Vandeleur Lee was a lodger in his parent’s house. From him, Shaw learned about singing techniques, and even had the ambition to become an operatic baritone. Mozart’s Don Giovanni, as he proudly proclaimed, was the most important item of his education. From Mozart he “gained the ability to say important things conversationally, and Shaw even adopted “Don Giovanni” as his nickname during his early London days.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Don Giovanni, “Don Giovanni, a centar teco”

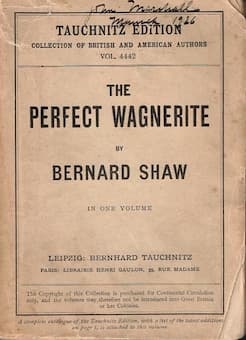

Shaw: The Perfect Wagnerite

Shaw claimed that he had “learnt force of assertion from Handel,” and he completely neglected Haydn. His essay The Perfect Wagnerite “combined a clear and entertaining interpretation of the myth in terms of the capitalist society.” Verdi remained one of his favorites, but Rossini and Mendelssohn fared not well. He took up the cause of Richard Strauss’ Elektra, and supported British composers including the works of Arnold Dolmetsch. He made friends with Elgar, but turned down his request for an opera libretto. Nevertheless, he helped Elgar to gain a commission from the BBC for his Third Symphony.

George Bernard Shaw, 1936

Shaw was even able to listen to Schoenberg and Scriabin, but couldn’t stand Brahms. He considered the Brahms Requiem “a solid piece of musical manufacture that could only have come from the establishment of a first-class undertaker.” Shaw called it a “colossal musical imposture patiently borne only by the corpse.” Shaw would eventually call his animosity towards Brahms “my only mistake,” but both would probably have agreed that “hell is full of amateur musicians.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: A German Requiem, Op. 45