The word “Canon” actually means rule, or law, and it is one of the most important elements in counterpoint. Clearly, it is musically very powerful when a previously heard melody reappears in another voice as a canon. Both voices maintain independence, yet they sound like they belong together because they are doing the same thing, just at different points in time. A canon can convey a multitude of extra-musical meanings, whether Bach is signing his name or Beethoven is making fun of a patron.

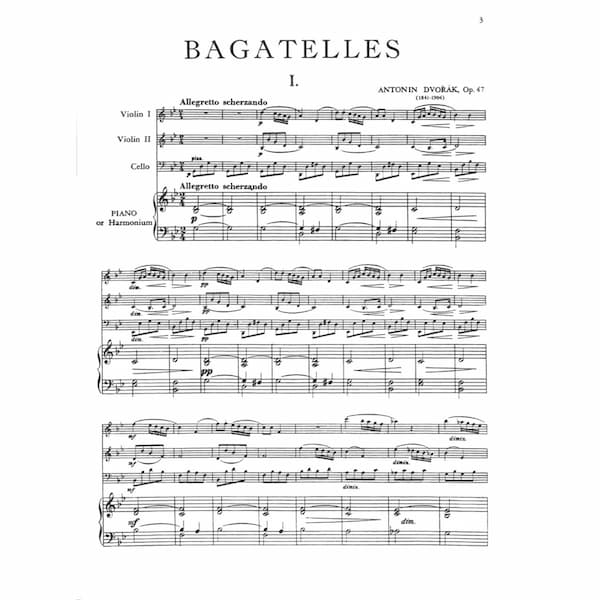

Dvořák’s Bagatelles Op. 47

Canonic technique is certainly one of the most useful devices in a composer’s toolbox, and when Antonín Dvořák was asked to write a piece for a private circle of chamber enthusiasts, he produced a quartet for two violins, cello and harmonium originally entitled “Malickosti” (Bagatelles). Composed in only 12 days at the beginning of May 1878, the Bagatelles were clearly aimed for the home market. His publisher Simrock remarked that Dvořák “could pull melodies out of his sleeve.” Apparently, he could also pull canons out of his sleeve, as the delightful and lyrical slow movement is a close canon between first violin and cello.

Antonín Dvořák: Bagatelles, Op. 47, No. 4 “Canon: Andante con moto” (Domus Ensemble)

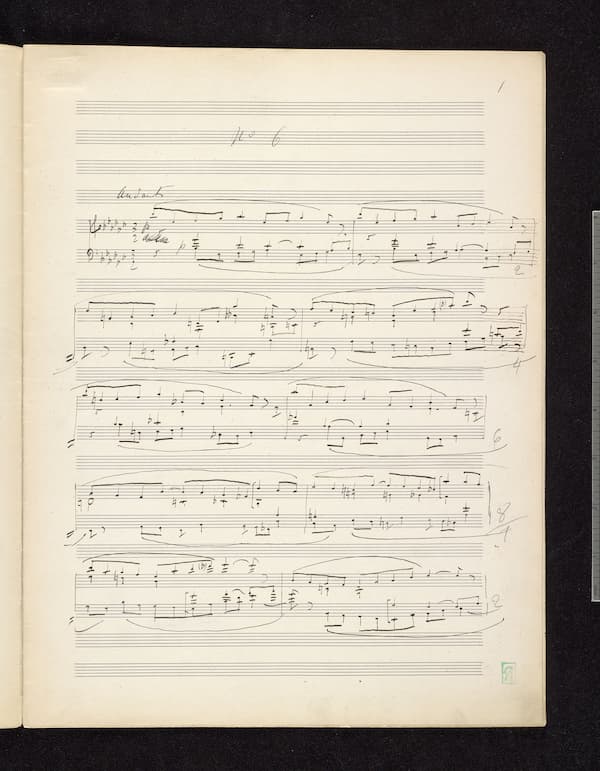

Fauré: Prelude Op. 103, No. 6

Gabriel Fauré told Marguerite Long in 1910, “In piano music, you cannot make use of padding: you have to pay cash and make things interesting all the time. It is perhaps the most difficult genre if you also want to be as satisfying as possible—and I endeavour to do so.” To commemorate the Chopin centenary in 1910, the publishers Heugel and Durand solicited compositions in honour of the old master. As such, Fauré composed and published three Préludes shortly before Debussy issued his complete First Book of Préludes. Fauré did add six more Préludes over the summer, but he let his collection rest at nine rather than pushing on to complete the originally planned twelve. Probably intended to be played as a cycle, these musical jewels clearly represent the peak of Faure’s art. In fact, the Prélude No 6 in E-flat minor is the most classical piece in this set. For one, it is constructed as a strict canon at the octave and in terms of expressiveness, Aaron Copland suggests, “it can be placed side by side with the most wonderful of the Preludes of the Well-Tempered Clavier.”

Gabriel Fauré: Préludes, Op. 103, No. 6 (Paul Crossley, piano)

Raoul Dufy’s Regatta at Cowes, 1934

Raoul Dufy (1877-1953) was a French Fauvist painter who developed a colourful, decorative style that became fashionable for designs of ceramics and textiles, as well as decorative schemes for public buildings. Although Igor Stravinsky had never personally met Dufy, he nevertheless penned a short composition, “In Memoriam,” for a string quartet in 1959. The Double Canon originated as a duet for flute and clarinet but was later expanded to a string quartet. Although brief, this double canon features a flurry of contrapuntal activity, and by adhering to Schoenberg‘s 12-tone method, the counterpoint becomes austere and somewhat obscure. However, as a critic has written, “the piece sounds supremely natural, and yet the canons are rigorously strict; the retrograde forms also reverse the rhythms of the original, a device that can be heard and is important for the work’s expressive effect.” In this memorial composition, the canons are always comprehensible, and they help to make the emotional content of the music translucent.

Igor Stravinsky: Double Canon (Otis Igleman, violin; Israel Baker, violin; Sanford Schonbach, viola; George Neikrug, cello)

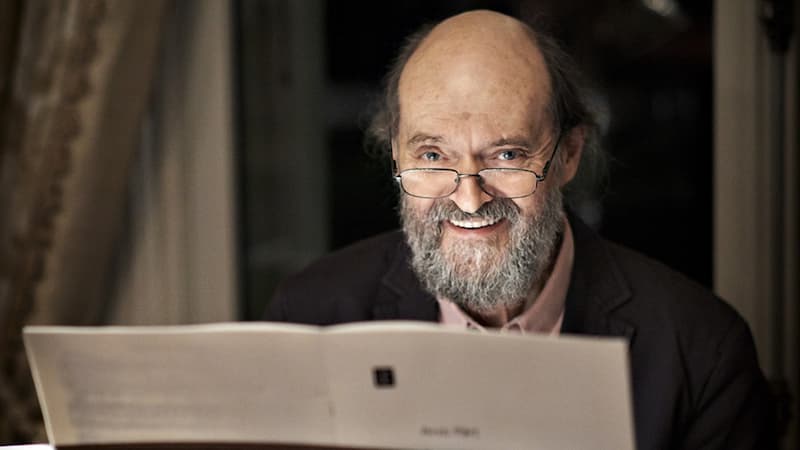

Arvo Pärt

Imitative polyphony and contrapuntal technique are found throughout the music of the 20th century. Schoenberg composed canons, as did Stravinsky, Bartók, Webern, Messiaen and Boulez. Canon provides composers with a procedure for exploring melodic and harmonic space without relying on functional harmony as a guide. It has been argued that “the resurgence of canon in the late 20th century was a completely natural development, a reassertion of the most basic elements of music: melody and repetition.” Minimalism was founded in part on the principle of continuously adjusting canon, and other canonic revivals are closely related to early musical procedures such as “mensuration canons” rigorously composed during the Renaissance. In this type, the following voice imitates the leading voice by some rhythmic proportion. This canon once again gained currency in the 20th century, and it provided the foundation of Arvo Pärt’s Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten. “In the past years,” Pärt writes, “we have had many losses in the world of music to mourn. Why did the date of Benjamin Britten’s death—4 December 1976 touch such a chord in me? During this time, I was obviously at the point where I could recognise the magnitude of such a loss. Inexplicable feelings of guilt, more than that even, arose in me. I had just discovered Britten for myself. Just before his death, I began to appreciate the unusual purity of his music… For a long time I had wanted to meet Britten personally, and now it would not come to that.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Arvo Pärt: Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten (Stuttgart State Orchestra; Dennis Russell Davies, cond.)