Pianist and composer Franz Liszt was born on 22 October 1811 in the Hungarian village of Doborján.

Here are a few points about his life that you should know:

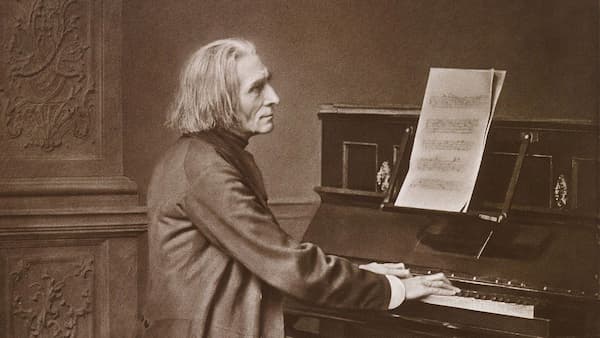

Carbon print circa 1869 by photographer Franz Hanfstaengl

– Liszt was part of a wave of virtuoso performers from the Romantic Era who redefined instrumental technique and artistic philosophy. He became extremely invested in ideas about the future of not just music, but the arts and life in general. Along the way, he was inspired by literature by Goethe, Victor Hugo, and other figures.

– Liszt was known for his rock and roll lifestyle. He had a variety of scandalous romances, including with intelligent rebellious highborn women like Marie d’Agoult and Carolyn Sayn-Wittgenstein. They were far from the only ones to fall under his spell. Women across Europe were so taken by his magnetic onstage presence that the word “Lisztomania” was coined to describe it.

– Liszt treasured his Hungarian heritage. During the 1848 revolutions that swept across Europe, he became involved with pro-Hungarian political movements. He was inspired to engage politically by writing music inspired by Hungarian folksong and funding Hungarian causes.

– He composed a huge amount of music, much of which is underappreciated today. He became involved in a heated debate about aesthetics that became known as the War of the Romantics. Some leading musicians believed that music should hew closely to inherited forms. Others, like Liszt, believed that music of the past should be largely rejected and that new work should encompass extra-musical ideas in philosophy and art. To help buttress his ideas, and with the encouragement of his long-time partner, he composed…a lot.

– He had a lifelong fascination with death and religion. After the deaths of two of his children, Daniel and Blandine, he moved to a monastery and received minor orders in the Catholic Church. Much of his music from this time has a sacred inspiration. But his obsession with death is a theme that listeners can trace all the way through his career.

Without a doubt, Franz Liszt was one of the most fascinating people in the history of classical music.

Join us as we look at eleven of his most famous pieces, dating from 1822 to 1885:

Variation on a Waltz by Diabelli (1822)

Liszt’s father was a musician who worked for the noble Esterházy family. He began teaching his son Franz piano at the age of seven. The following year, he began composing. The year after that, he began performing publicly. Soon he was studying in Vienna under Beethoven’s student, Carl Czerny.

In late 1823 or early 1824, Liszt’s first piece was published. It was a brief variation on a tune composed by music publisher Anton Diabelli, who, in a smart bit of networking, was commissioning variations from different composers. Czerny appeared in the anthology, and it seems likely that he pushed to have his eleven-year-old student Liszt included, too.

Anton Diabelli

This is a very early and very brief piece, but one can already hear Liszt’s penchant for Romantic-style musical drama.

La Campanella (1838)

As Liszt matured, he became more and more interested in pushing technical boundaries.

In 1832, the year he turned twenty-one, he heard a violinist named Niccolò Paganini, who had revolutionized violin playing. Liszt vowed to do for the piano what Paganini had done for the violin and spent his early twenties concentrating on honing his technique.

In tribute to his new idol, Liszt arranged several of Paganini’s works for solo piano. The most famous example of this is “La Campanella” (“The Little Bell”), a rearranged movement from Paganini’s second violin concerto.

“La Campanella” features daring leaps for the pianist’s right hand and intensely dramatic trills.

This arrangement is an homage to all of the inspiration Paganini gave to Liszt, and to the spirit of daring Romanticism that animated both men.

Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 in C# Minor (1847)

In the 1840s, there was a continent-wide conversation about the roles of monarchies, aristocracy, and the necessity for democratic reform. Of course these conversations also came hand-in-hand with discussions about national identity.

Liszt was proud of his Hungarian heritage, and he wrote that pride into this rhapsody. It’s an irresistible celebration of the rich legacy of Hungarian-style folk music…even if it’s not, strictly speaking, authentic Hungarian folk music!

The second “Hungarian Rhapsody” has appeared as the soundtrack to countless pop culture moments, including in cartoons featuring characters like Ben and Jerry and Bugs Bunny.

Liebestraum No. 3 (1850)

Liebestraum translated means “Dreams of Love.” In Liszt’s hands, a Liebestraum became a song without words.

The most famous of Liszt’s Liebestraums is the third. This passionate Liebestraum was inspired by a poem by Ferdinand Freliligrath, which calls upon readers to love deeply before death takes them.

This work highlights how Liszt looked to other arts for inspiration, as well as his ability to write deeply affecting music.

Beethoven Symphony No 5 (1863-64)

In an era of frequent live performances and Spotify playlists, it’s easy to forget that in Liszt’s day, hearing music played at home on the piano was the best way of hearing and learning orchestral scores.

Over the course of his career, Liszt transcribed all nine of Beethoven’s symphonies. He was in a unique position to do so, given that he studied under Carl Czerny, who himself had been a pupil of Beethoven, and Liszt had even met Beethoven when he was a child.

These transcriptions provided virtuoso pianists a unique opportunity to explore and experience Beethoven’s great symphonies at home, no orchestra required. They are works of art in and of themselves. Musicologist Dr. Alan Walker once wrote that they “are arguably the greatest work of transcription ever completed in the history of music.”

Piano Concerto No. 1 (1835-56)

Liszt’s first piano concerto was the work of decades. He began composing the themes from it in 1830, when he was nineteen but only premiered the finished work when he was forty-four.

This concerto is unique for a variety of reasons, but one of the most noteworthy is the fact that it’s all one piece and not broken up into three movements like almost every other concerto of the era.

This illustrates Liszt’s willingness to experiment with musical tradition and form: a hallmark of the Romantic Era’s obsession with authentic expression of the self, as opposed to blindly following tradition.

This work contains multitudes. At various times, it is daring, delicate, dramatic, and dreamy. It also proves that although Liszt was a true master of piano technique, he also valued evoking emotional responses in his listeners.

Totentanz (1847-53)

Totentanz (or Dance of the Dead) is a macabre work for piano and orchestra that speaks to Liszt’s lifelong preoccupation with questions about religion, as well as the drama inherent in the Catholic tradition.

Liszt’s father and mentor Adam Liszt had died when Franz was only fifteen. That early loss helped fuel his grim, decades-long fascination with death and its effects on the living.

This work begins by quoting a Gregorian plainchant known as the Dies Irae (the Day of Wrath), a melody that, over the centuries, has become musical shorthand for death.

Listen to how percussively Liszt treats the piano and how thrilling – and terrifying! – the effect is.

Mephisto Waltz No. 1 (1856-61?)

A similar theme is at play in Liszt’s devilishly difficult, demonic “Mephisto Waltz No. 1.” When he was writing this work, Liszt took inspiration from Nikolaus Lenau’s verse drama Faust, which appeared in 1836.

The following explanation appears in the score. (Note that Mephistopheles is a demon from German folklore.)

There is a wedding feast in progress in the village inn, with music, dancing, carousing. Mephistopheles and Faust pass by, and Mephistopheles induces Faust to enter and take part in the festivities. Mephistopheles snatches the fiddle from the hands of a lethargic fiddler and draws from it indescribably seductive and intoxicating strains. The amorous Faust whirls about with a full-blooded village beauty in a wild dance; they waltz in mad abandon out of the room, into the open, away into the woods. The sounds of the fiddle grow softer and softer, and the nightingale warbles his love-laden song.

Once again, Liszt demonstrates how inspired he was by literature and stories, and how he felt a real freedom to compose outside of the standardized musical forms, as long as doing so would produce an emotional effect.

Faust Symphony (1854, 1857-61, 1880)

Liszt’s extra-musical Faust inspiration culminated with his Faust Symphony. This seventy-five-minute-long work for chorus and orchestra doesn’t tell the story of Faust, strictly speaking. Rather, it creates detailed character profiles of Faust, Gretchen, and Mephistopheles – or, maybe even Faust’s own conception of himself, Gretchen, and Mephistopheles.

Sonata in B-minor (1853-54)

By the early 1850s, upon the advice of his partner, writer Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, Liszt had largely ceased touring and turned his considerable creative energies to composition.

One of the major works he composed after this shift in focus was the B-minor piano sonata. This is a very intense, personal, and experimental piece.

Carolyn Sayn-Wittgenstein

Many musicians didn’t like Liszt’s new direction. He dedicated it to composer Robert Schumann. His wife, the great pianist Clara Schumann, fretted because she hated it: “This is nothing but sheer racket – not a single healthy idea, everything confused, no longer a clear harmonic sequence to be detected there! And now I still have to thank him – it’s really awful.”

Others disliked it, as well. However, it proved to be a work before its time, and it gained popularity by the early twentieth century.

Les préludes (1850-55)

Over the course of his career, Liszt wrote thirteen symphonic poems.

Symphonic poems are single-movement works for orchestra that portray an extra-musical subject, like a painting, novel, mythological figure, historical event, or the like.

You can see why Liszt was attracted to this genre, since he loved contemplating the connections between real-life subjects and abstract music.

Les préludes (“The beginnings”) started life as a relatively brief overture for a set of four choral works called Les quatre éléments (“The four elements”).

Eventually, Liszt lengthened the overture until it became its own work. In this revised work, he portrayed archetypal Romantic Era motifs like sea storms and pastoral love.

Christus (1866-72)

In 1859, Liszt’s son Daniel died. Then, in 1862, his daughter Blandine died, too, shortly after giving birth to her son.

These twin losses devastated Liszt and re-ignited his ever-simmering fascination with death and religion. In 1863, he moved to Rome and soon received minor orders, choosing to live a spartan ascetic life.

During this time he embarked on Christus, a three hour oratorio for chorus, vocal soloists, and orchestra. Christus is split into three parts, covering Christ’s birth, the visit of the Magi, and his death and resurrection.

En rêve: Nocturne (1885)

In 1881, a seventy-year-old Liszt fell down his hotel stairs. After the fall, he had to remain immobile for eight weeks, and he never really recovered.

At the same time that his health – both mental, emotional, and physical – declined, his personal musical style evolved into something that was much simpler and more desolate.

His “En rêve” (Dreaming) from 1885 is a prime example of this. More and more, he valued simplicity, clarity, and expressiveness over virtuosity.

Conclusion

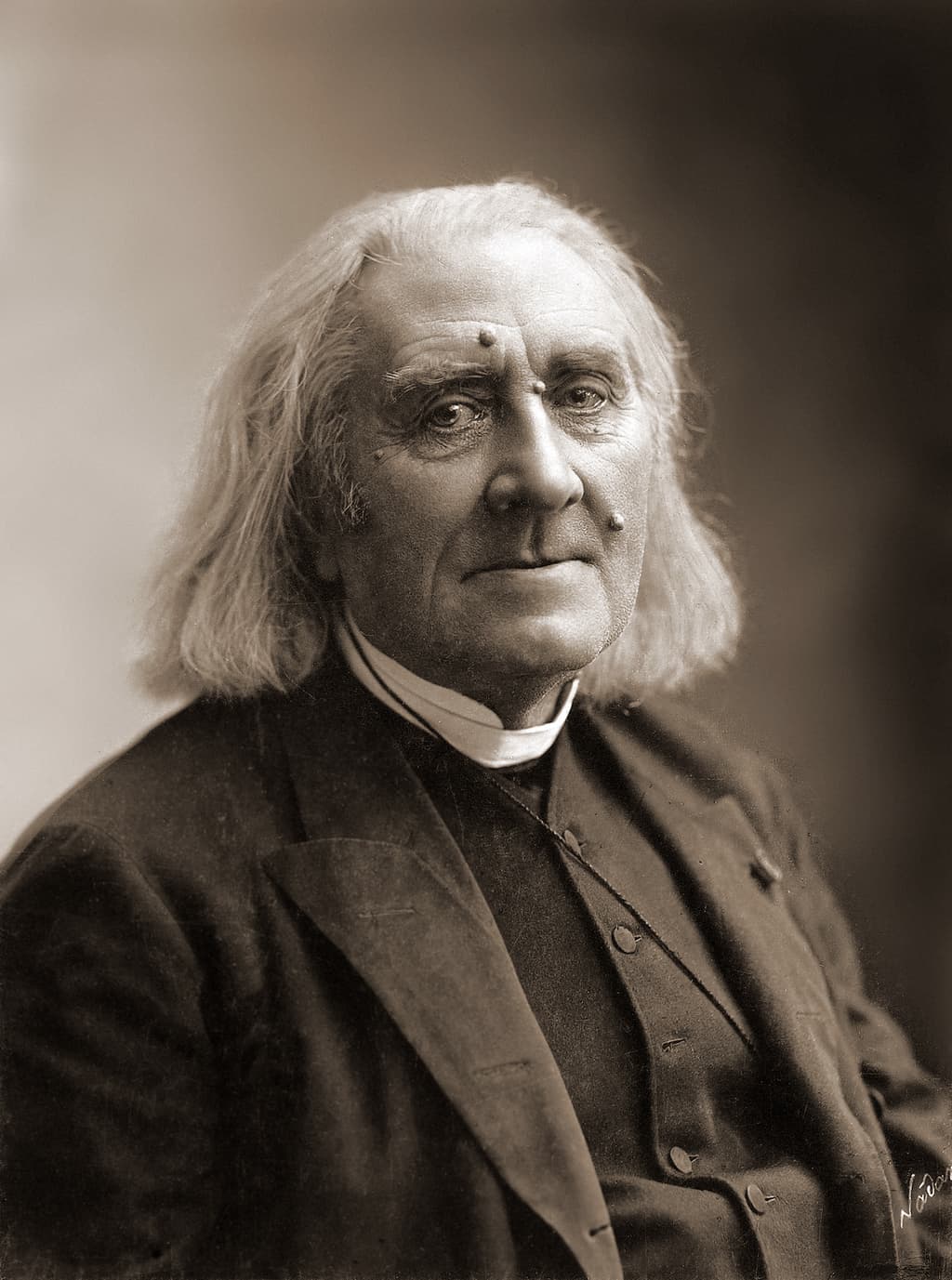

Franz Liszt in 1886

Franz Liszt died in July 1886 in Bayreuth, Germany, of pneumonia. Tributes immediately began pouring in.

Whether one loves or hates his music, it’s undeniable that he was one of the most influential classical musicians of the nineteenth century…and also one of the most interesting.

Learn more about the fascinating life and work of Liszt.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Good tribute to the great Liszt. Compelling selections.