Learning scales is an essential step on the road to develop our playing. Once we learn the fingerings, we should be able to spontaneously play the scales that appear in the music even on sight. Learning all the modes can be challenging but I am going to simplify the load for those of you who are confused!

First, let’s define the scale:

© rcmusic.com

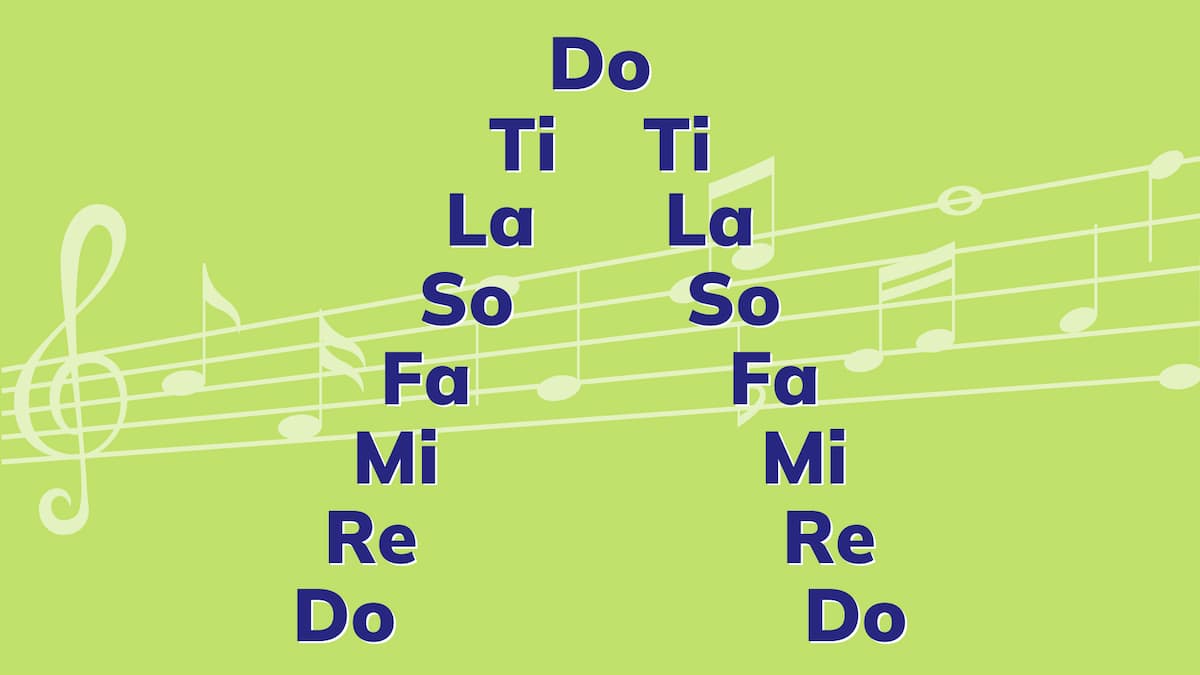

We only have 12 notes to worry about. A scale is a set of 7 of these notes, which are organized stepwise between one note and the same note an octave higher. A semitone or a half step is the closest note next to it. A whole tone comprises two half steps. A sharp (or hashtag) raises a note one half step, and a flat lowers the note a half step.

All scales are an arrangement of the intervals, or the distance to its nearest neighbor, in a pre-determined order. The major and minor scales are only two of the modes we encounter. The major scale, as my mother used to bellow, is TWO whole, one half; THREE whole one half, or WWH – WWWH. The major scale, also known as the Ionian mode, is ubiquitous in our music literature. If one starts on C on the piano, and we play the white keys only, we have the above-mentioned pattern.

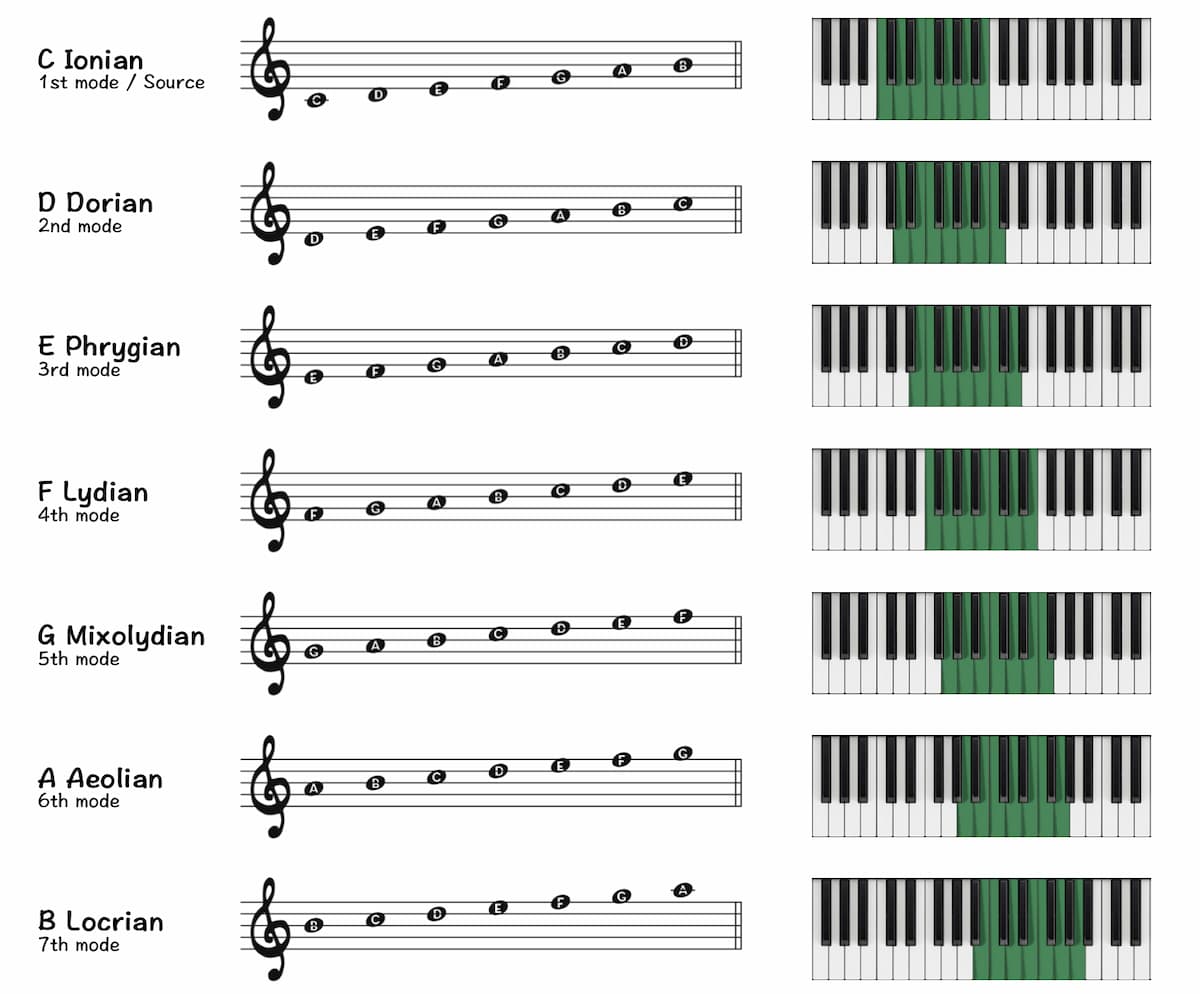

There are seven modes that we musicians try to become familiar with.

Ionian (natural major scale); Dorian (a minor scale with a raised 6th); Phrygian (a minor scale with a lowered 3rd and 2nd); Lydian (a major scale with a raised 4th degree); Mixolydian (a major scale with a lowered 7th tone); Aeolian (natural minor scale); Locrian (a minor scale with a lowered 3rd, 2nd, and 5th).

As clear as mud? Some colleagues have used an acronym to try to remember IDPLMAL:

“I Don’t Prefer Loud Music After Lunch!”

“I Don’t Play Loud Music After Lunch!”

“I Don’t Play Loud Music About Love!”

And there are a few other creative variations:

“I Don’t Particularly Like Modes A Lot…” And my favorite,

“I Don’t Particularly Like Mashed Artichokes Lately.”

When the modes all begin on the note middle C as in the following graph, it clarifies the different intervals and the alterations that occur within the modal scales:

Modes beginning on C

But for those of us who are confused by this, we might try to learn each mode by playing only on white keys, each mode beginning on a different note, so as to hear the differences first:

And here’s a visual for learning modes this way!

Modes of the Major Scale

To reinforce our understanding, it helps to hear the modes in various compositions.

The Dorian mode

(D to D on the white keys) (and D for Dorian)

This mode is beautiful, and one can hear this mode in the opening of Sibelius Symphony No. 6 and the piece Fêtes, (Festivals) from Nocturnes by Claude Debussy. The opening dance tune— a quick upward scale— is the Dorian scale. In fact, Debussy, in the first 30 seconds of the piece, incorporates three modes, the Dorian, the Lydian, and then the Mixolydian. In the middle section a March appears again in the Dorian mode. Towards the end of the piece the march music and the dance music are superimposed, that is both the Dorian and Mixolydian modes, and while alternating 5/4 and 3/4 meters. Brilliant!

Claude Debussy: Nocturnes – No. 2 Fetes (Lyon National Orchestra; Jun Märkl, cond.)

The Phrygian mode

(E to E on the white keys)

Phrygian mode is a minor mode with a lowered 7th or leading tone, but its main characteristic is that it begins unusually enough with a half tone. It’s a mode that sounds Spanish and is used in flamenco music. Composers use it in Hebrew music and for exotic or Oriental effects. Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 is a good example, as is Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade. Even Brahms used the Phrygian mode in the solemn sounding and majestic slow movement of his 4th Symphony. Listen to the Ralph Vaughan Williams Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis. Written for double string orchestra and string quartet, and based on a 16th-century chant by Thomas Tallis, it is a haunting and beautiful work that utilizes not only this mode but also antiphonal effects, as the string quartet is usually seated at a distance.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (Sinfonia of London; John Wilson, cond.)

The Lydian mode

(F to F on the white notes)

Another major mode, this time with a raised 4th degree, can be heard in Prokofiev Lieutenant Kije Suite movement one, The Birth of Kije in the piccolo solo near the beginning. Beethoven also composed in this mode in his String Quartet in A minor, No. 15 slow movement.

We should draw your attention to several other works that use the Lydian mode to portray Polish folk and dance music such as Chopin Mazurka 15, Op. 24 No. 2. But listen to the first theme played by the solo violin in Korngold’s lush Violin Concerto in D Major Op. 35. Dedicated to Alma Mahler, the widow of Gustav and Korngold’s mentor, it is performed by the great violinist Jascha Heifetz who premiered the piece in 1947.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35 – I. Moderato nobile (Jascha Heifetz, violin; New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Efrem Kurtz, cond.)

The Mixolydian mode

(G to G on the white keys)

This is one of the most popular modes in jazz and rock music—a major mode with a lowered 7th or leading tone. The Beatles song Norwegian Wood and jazz and Afro-Cuban music such as Danzon, the Cuban dance from Fancy Free by Leonard Bernstein, are two examples. Debussy portrays grandiosity in his piano work Sunken Cathedral by using the Mixolydian mode.

Bernstein Conducts Danzon from Fancy Free

The following two modes are more rare in classical music.

The Aeolian mode

(A to A on the white keys)

This mode, also called natural minor mode, features the lowered leading tone. Dvořák Symphony in E minor No. 9 Op. 95 “From the New World” utilizes the pentatonic scale, and the lowered seventh in the second subject of the first movement to capture the spirit of American folk music and spirituals. Let the conductor Gerard Schwarz show you!

Dvořák: 9th Symphony: Musical Analysis by Gerard Schwarz

The Locrian mode

(B to B on the white keys)

This mode is rarer still, perhaps because it utilizes the tritone—the “Devil’s” interval, an interval of three whole tones such as C to F# or if one uses white notes only on the piano, F to B. Nonetheless Sibelius uses this mode in his gloomy, austere Symphony No. 4 in A minor Op. 63. The first movement opens in somber fashion with the lowest timbres and then a cello solo, with the dominating sonority of the tritone—C-D-F#-E. The interval, pervasive in the symphony, creates a sense of foreboding.

Jean Sibelius: Symphony No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 63 – I. Tempo molto moderato, quasi adagio (Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra; Leif Segerstam, cond.)

The Ionian mode

Or the major scale (C to C on the white keys)

It is ever-present in Western music. The long list of momentous classical music works in C major include numerous piano works and concertos. The character of this key is triumphant in Beethoven Symphony No. 5 finale and sparkling in Mozart Symphony No. 41 the Jupiter. It is imaginative and captivating in Sibelius’s hands in the Symphony No. 7, while gargantuan and gripping in Shostakovich Symphony No. 7 in C major Op 60, the “Leningrad”.

Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 7 in C Major, Op. 60, “Leningrad” – I. Allegretto (Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra; Vasily Petrenko, cond.)

In the above-mentioned composers’ hands, the modes sound ravishing. Shall we adjust our acronym?

“I Do Perform Lovely Modes Always Luminously.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter